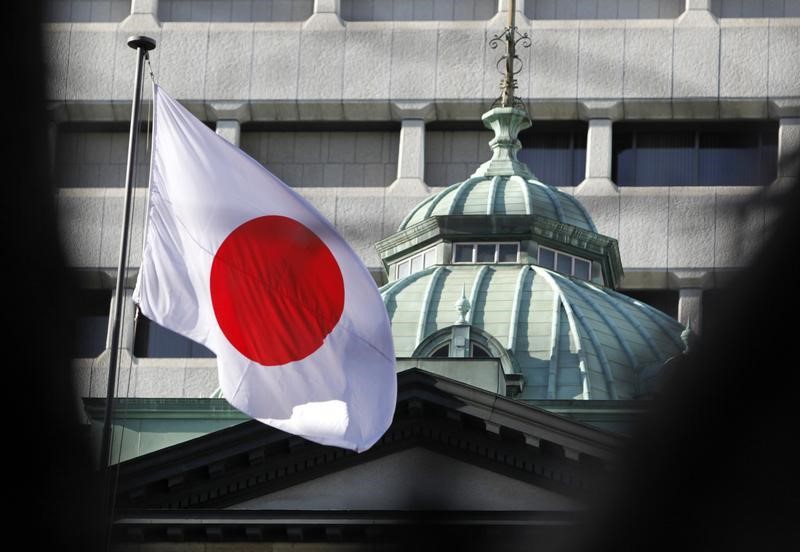

(Bloomberg Opinion) -- It’s decision time again for the Bank of Japan, and the most important issue for markets boils down to this: Will there be a hint from policymakers that the side effects of monetary easing are beginning to worry them?

The answer to that question may lie as much in geopolitics as in economics.

The BOJ is in a corner, not least because it may have to shift more of its exchange-traded-fund purchases to a broader benchmark like the Topix, and away from the Nikkei 225, “a Flintsones index from an abacus age,” according to CLSA analyst Nicholas Smith.

The central bank’s real difficulty lies in the bond market. Even with negative interest rates (since January 2016) and yield-curve controls (since September 2016), the 2 percent inflation target for Japan remains elusive. More worryingly, the impact of those policies now poses a threat to Prime Minister Shinzo Abe’s larger game plan.

Consider the consensus analyst estimate of the one-year-forward return on assets for lenders in the Topix Bank Index. It was 0.39 percent in December 2015, just before the imposition of negative interest rates. For lenders in the S&P 500 index, the similar return-on-asset expectation was 0.95 percent in December 2015, when Donald Trump’s surprise victory in the U.S. presidential election was nowhere in sight.

Fast forward to now, and analysts have bumped up their return-on-asset expectations for U.S. lenders to 1.2 percent, while scaling down forecasts for Japanese banks to 0.3 percent. What used to be a profitability gap of 3:1 is now a 4:1 advantage in favor of the Americans.

Negative interest rates have flattened Japanese banks’ ability to earn a spread on deposits. Should the BOJ not try to build them a new profit ladder, their ability to generate capital for future growth will be constrained; and without that capital, they’ll find it hard to go head-to-head with Beijing’s belt-and-road infrastructure projects in Asia and beyond.

Recall that Abe’s popular appeal in the December 2012 election was built on the promise of a great reset, one that would make Japan reemerge as a force by preventing its aging, shrinking population from pulling the nation into a vortex of deepening deflation and increasing irrelevance. However, the bold monetary experiment that his campaign required is now inhibiting banks’ expansion, militating against the prime minister’s goal of countering Chinese influence.

More than any threat to the stability of Japan’s financial system, this speed limit on Abenomics is the side effect BOJ Governor Haruhiko Kuroda needs to watch.

In 2017, the top Japanese lenders – Mitsubishi UFJ Financial Group Inc., Mizuho Financial Group Inc. and Sumitomo Mitsui Financial Group Inc. – saw a 19 percent slump in project-finance loans for which they were the main arrangers, to $27 billion, even though global activity dropped back by less than 3 percent, according to data compiled by Project Finance International.

One could argue that by making it hard for them to turn a profit at home, the BOJ is pushing even regional lenders like Iyo Bank Ltd. to hitch a ride with the state-backed Japan Bank for International Cooperation. Together with Japanese heavyweights, Iyo is also financing the construction of a hospital in Istanbul. However, a desperate hunt for yield in risky projects overseas is bound to lead to credit mistakes; a foreign lending boom backed by stable profitability at home would prove more enduring.

What will be the exact nature of Tuesday’s “Operation Tweaks,” as Nomura Securities analysts term the policy fine-tuning? Any major change to the current system of keeping the short-term policy rate at -0.1 percent – and holding the 10-year government bond yield at around zero – could be misconstrued as the start of a much-feared reversal of quantitative easing, a possibility that raised its head with Kuroda’s speech at the University of Zurich last November.

It may not be a bad idea, however, for the monetary authority to signal greater comfort with 10-year yields at, say, 0.25 percent, which Nomura says could be a new cap. Such a shifting of gears could cause some temporary panic. But refusing to throw a bone to the profit-starved banks could eventually be more expensive to Abenomics.