(Bloomberg Opinion) -- In 2014, a group of reform-minded conservatives released “Room to Grow,” a set of essays charting a new path forward for the Republican Party. The fundamental concern of these self-styled “reformocons” was that classic Reagan-era policy — lower top marginal tax rates, the privatization of government services and aggressive deregulation — was at best uninspiring and at worst unhelpful to the party’s core demographic of white working-class voters. This concern would prove prescient, but not in the way reformocons hoped.

The party establishment entertained the reformocons’ ideas but failed to incorporate them. Donald Trump, meanwhile, instinctively grasped the underlying ethos and attached xenophobic anxieties about trade (with China) and immigration (from Latin America). His victory in 2016 forced the reformocons — two of whom are Bloomberg Opinion colleagues — into a bout of soul-searching.

One camp regards Trump as a flawed messenger of an essentially correct vision. They see the goal of maximizing economic growth as the source of working class pain. Increased trade and immigration may be good for the GDP, they contend, but they are bad for the American worker. A more worker-centric approach would raise tariffs and reduce immigration, both illegal and legal.

The opposing camp sees economic growth as essential to improving the fortunes of the working class. Higher wages are driven by innovation, which can only thrive in an open, competitive marketplace. This camp regards the emphasis on trade and immigration restrictions as a threat to the principles of a free capitalist society, if not a capitulation to leftist thinking.

Not only does the second camp have the better economic argument, but the first group has a deeper problem: They’ve misdiagnosed the ailments of the American working class and attributed to public policy the consequences of deeper economic forces.

Take the issue of trade. The first camp acknowledges that free trade leads to lower prices for U.S. consumers. The cost of those low prices, they argue, is too high: the hollowing out of American manufacturing. High tariffs on foreign goods might reduce overall consumption in the U.S., the argument goes, but they would bring production back to the heartland.

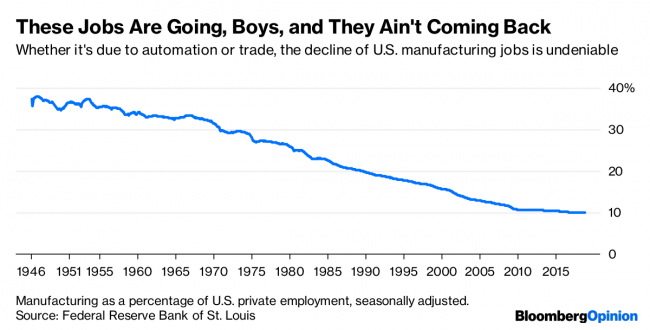

How much of the loss of U.S. manufacturing is due to trade and how much is due to automation is a question economists have been debating for decades. (For the record, I think the issue is more complex than many academics say, and that the distinction between trade and automation is vaguer than it might appear.) Still, let’s concede that trade played a substantial role in the rapid decline in manufacturing employment since the late 1960s.

High tariffs, however, would not have prevented that. The loss of those jobs has its roots not in the failure of public policy but in the success of private enterprise.

The U.S. dominates the world in entertainment, information technology and financial services. Cash pours in to Hollywood, Silicon Valley and Wall Street from around the world, creating an enormous demand for dollars. This raises the value of the dollar, causing U.S. exports to be more expensive and imports to be cheaper.

In response, Americans buy more from abroad, foreigners buy fewer U.S. goods, and the trade deficit rises. The rising trade deficit sends cash out from America to balance the inflows to its dominant sectors. Once the two are in equilibrium, the value of the dollar stabilizes.

What would happen then if the U.S. slapped tariffs on foreign imports? The price of those foreign goods would rise, of course. At first, Americans would buy fewer of them, putting downward pressure on the trade deficit and reducing the outflow of dollars from the US.

It would not, however, put a dent in the money flowing into Hollywood, Silicon Valley and Wall Street. The global demand for their products and services is intense. With less cash flowing out of the U.S., but the same amount flowing in, the value of the dollar would again begin to rise. It would keep rising until equilibrium was again restored — and the only way to do that would be for the U.S. to reduce its exports or increase its imports.

As a result, U.S. manufacturing would still shrink — and U.S. consumers would pay higher prices. The tariff would in effect act as a regressive tax on manufactured goods generally. The inequities it sought to eliminate would actually get worse.

This result is a familiar example of what happens when the government tries to reconfigure the production side of the economy. An attempt to boost working-class wages by limiting immigration would fail for similar reasons, though the mechanics of the process are different.

This, and not a fetishization of GDP, is why economists since Adam Smith have advised governments to concentrate their efforts on expanding the overall productive capacity of the economy, rather than on micromanaging individual markets. Conservative policy wonks do their audience a disservice when they forget this age-old lesson.