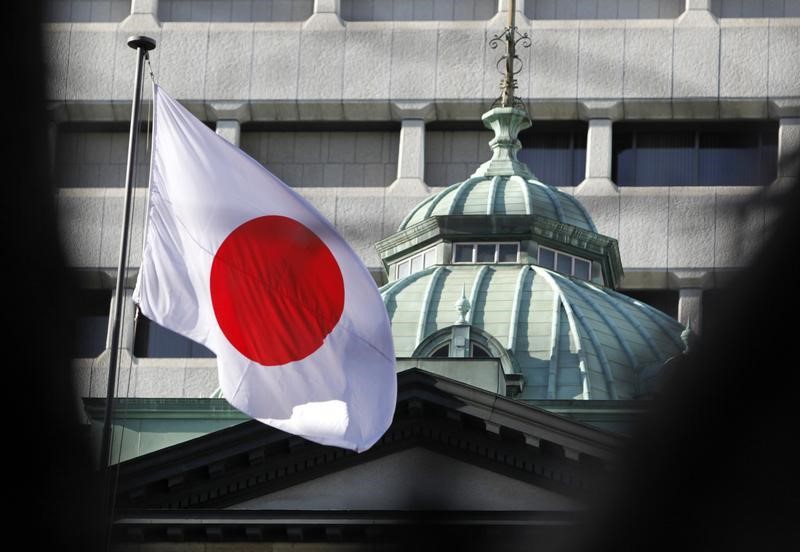

(Bloomberg View) -- The Bank of Japan’s policy meeting Thursday and Friday is likely to focus on its inability to spark a sustained rise in the inflation rate despite years of negative interest rates and quantitative easing. That emphasis would be missing the point. The BOJ’s big problem is that its policies have effectively forced Japanese investors out of bonds and into equities, which are now tanking, and that it has not been able to fix the damage done to banks by negative rates. The Topix Index is off 13 percent since the January peak, and Japanese banks have underperformed the broad index by almost 20 percent since the end of 2015.

The good news is that investors are probably wrong in sensing that the BOJ might be shifting into a hawkish mode. That course of action would do more harm than good because it would strengthen the yen, and there wouldn’t be an offsetting benefit.

The BOJ has an inflation target, so it’s natural that it measures monetary policy success in inflation terms. However, most major central banks have failed to reach their inflation marks. Nonetheless, economic performance has been strong globally in recent years. If the inflation process makes it difficult to hit the inflation target, all the central bank can do is keep trying.

Still, no one forced the BOJ to pursue negative rates in early 2016. That decision was based on the central bank’s view that it would be a way of providing additional stimulus. But forcing investors out of bonds and cheerleading them into equities is fine when equities are rising, but not when they are falling.

The Topix index of bank shares has dropped 10 percent since the end of 2015, while the broader Topix index has risen 13 percent. That makes it hard to argue that negative rates are beneficial. Japan’s 20-year government bond yields are 75 basis points higher than one-year yields, down from a spread of about 100 basis points before the move into negative rates. Borrow short, lending long is not very profitable for banks.

Compared with the rest of the Topix, Japanese banks are very close to their lows of the first quarter of 2016. There are two reasons for this weakness. The first has to do with translation effects, or the way companies report the effects of changes in exchange rates. Although the yen’s strength isn’t to blame for all the problems with Japanese banks, there is a close enough relationship between the currency and the Topix that it bears some responsibility.

The second reason is that, since 2017, Japanese banks have become more sensitive to interest rates. Figure 3 shows the relative performance of Topix, banks and Japanese five-year yields, but the dynamic applies to all maturities. The relationship is pretty tight.

Japanese equities overall are largely driven by global sentiment and the yen. Figure 4 shows the actual and estimated level for the Topix based on a regression of its movements compared with the S&P 500 and the yen since 2016. Broadly speaking, the Topix has gone up about one point for every 1 percent move in the S&P and yen. That is not a relationship that you would want to bet strongly against.

In theory, the BOJ cannot do much about the level of the S&P 500, but it might consider buying U.S. exchange-traded funds rather than domestic shares. Purchasing U.S. equities or the MSCI global index is much more benign than buying U.S. bonds. President Donald Trump would probably be upset if the BOJ started to buy U.S. notes, as some have suggested, but he may not be as bothered if the BOJ were to help the S&P 500. The knock-on effect would benefit Japanese equities almost one for one, and the foreign-exchange impact of weaker yen and stronger dollar would make it a double win.

That would provide scope for a gentle bump higher in Japanese bond yields to help the banks. BOJ policy makers would have to go about this carefully, conveying to the market that they were carrying out a one-off steepening of the yield curve, not stealth tightening. This may be more credible it were done as part of a stimulus package.

The BOJ’s problems run much deeper than inflation alone. Addressing them will require stimulus, a weaker yen, and a one-off upward shift in yields.

This column does not necessarily reflect the opinion of the editorial board or Bloomberg LP and its owners.

Steven Englander is the head of research and strategy at Rafiki Capital. He was previously the head of G10 currency strategy at Citigroup (NYSE:C) and the chief U.S. currency strategist at Barclays (LON:BARC).