The Federal Reserve appears to be approaching the end of its rate-hiking policy, based on estimates from the bond market and economic conditions. But there’s a wild card that could derail the forecast: inflation stays elevated for longer than currently expected.

Some analysts are warning that it’s premature to assume that substantially lower inflation is now fate. The recent surge in pricing pressure has not “turned the corner yet,” says an IMF official. Gita Gopinath, a deputy managing director at the fund, advises the Fed to “maintain restrictive monetary policy” until a “very definite, durable decline in inflation” is evident in wages and industries excluding food and energy.

Fed funds futures are pricing in a 60%-plus probability of a 25-basis-points increase at the next FOMC on Feb. 1. If correct, that would be the smallest increase since the central bank began lifting rates last March.

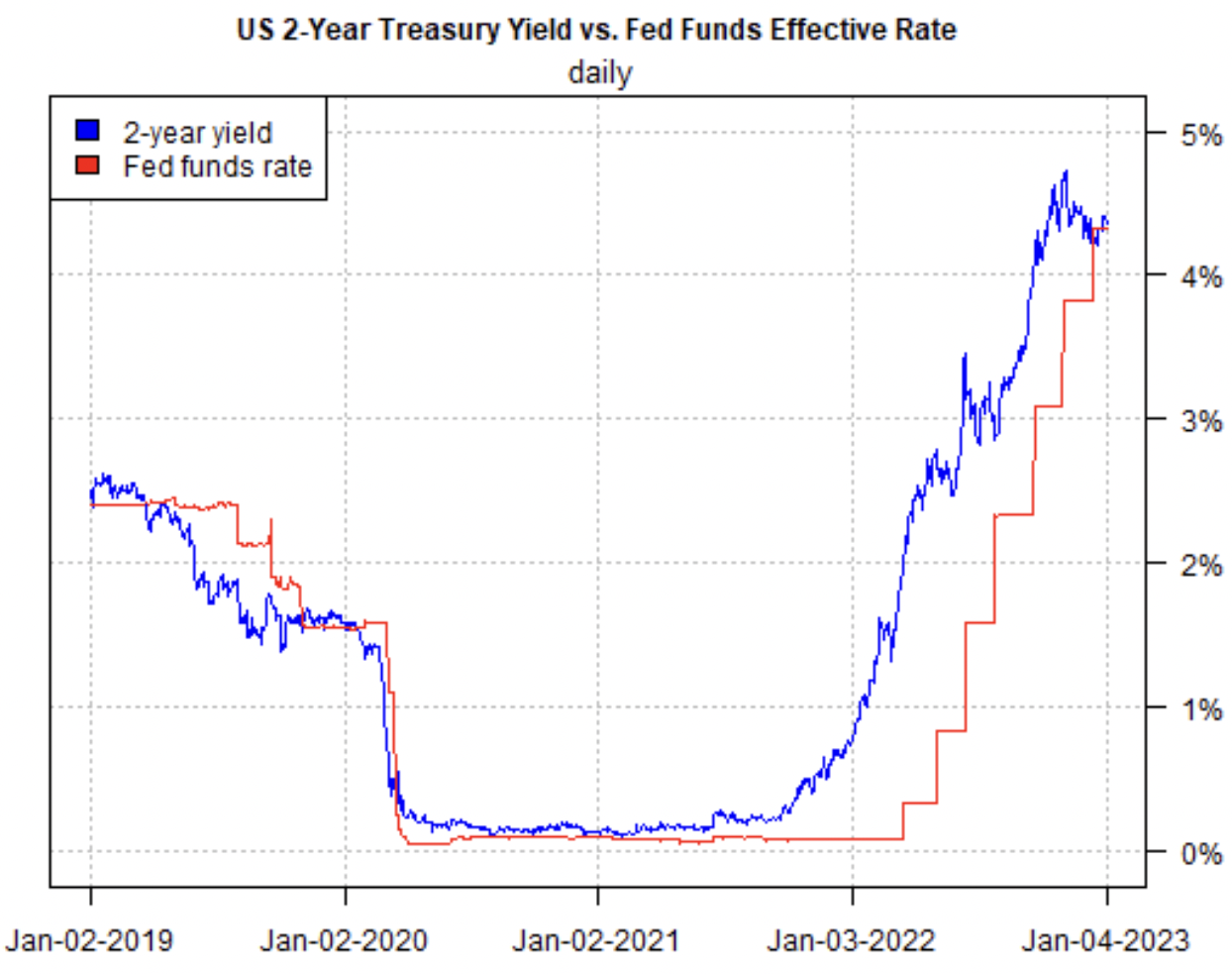

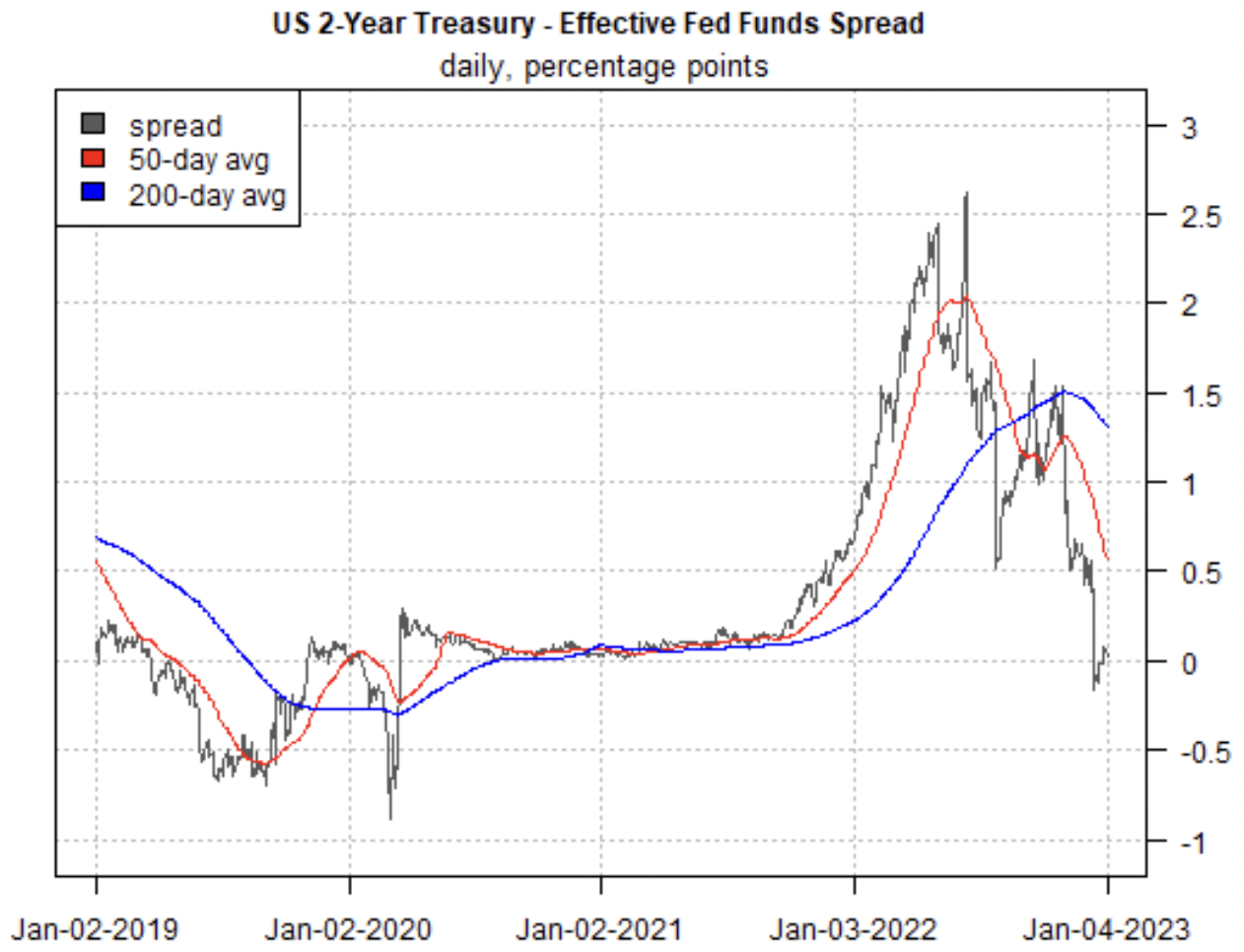

The Treasury market, however, appears to be anticipating that the end is near for Fed rate hikes, based on the relationship between the Fed funds target rate and the 2-year Treasury yield, which is considered the most-sensitive maturity for policy expectations. After an extended run of the 2-year rate running well above the Fed funds target – a forecast of rate hikes – the spread between the two has effectively vanished. That’s a sign that the market is now expecting that the rate-hiking regime is at or near its end.

For the first time in well over a year, the spread between the 2-year yield less the Fed funds rate is more or less zero.

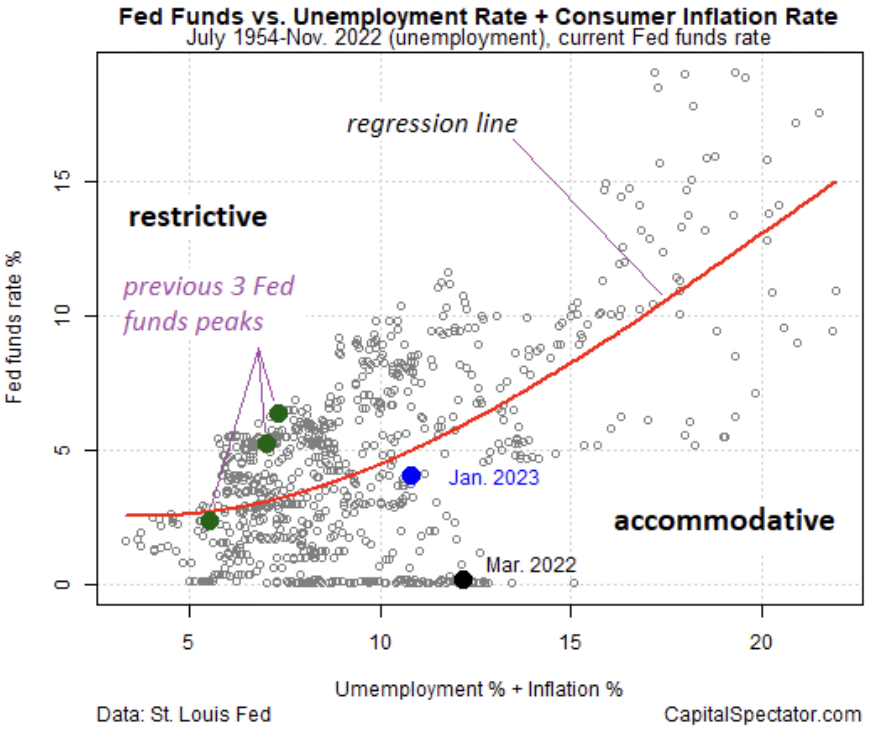

Using a simple model that compares the history of the Fed funds rate to unemployment and consumer inflation also suggests that the current level of interest rates is sufficiently restrictive relative to the macro conditions. In the chart below, the current level of Fed funds is close to an estimate of the optimal rate, given recent inflation and unemployment levels (blue dot).

In other words, Fed policy is in the zone that has signaled peak rate hikes in previous cycles. For perspective, current conditions are much less accommodative vs. the comparison with March 2022, when the Fed began raising rates.

The central bank could, of course, continue raising rates, regardless of Treasury market expectations and model-based forecasts. Much depends on incoming inflation numbers, economic growth (or the lack thereof), and the Fed’s confidence that pricing pressure has peaked, or not.

“The Fed still raising interest rates but balancing the pace and extent of rate hikes against the lagged impact of the cumulative policy tightening already in place,” advises Tim Duy, chief US economist at SGH Macro Advisors, in note to clients this week.

“Currently, the Fed anticipates that a policy rate of 5.125% will support the financial conditions necessary to meet its goal.”

On that basis, more rate are coming beyond Feb. 1 forecast for a 25-basis-points increase, which would lift Fed funds to a 4.50%-to-4.75% target range. The Treasury market, however, seems to be betting that one more small hike will be followed by a pause – an outlook that will be strengthened if the next round of economic data suggests that growth is slowing or worse.