Everyone agrees investors will be paying close attention to the March consumer price index release from the U.S. Labor Department today [Tuesday]. What analysts don’t agree on—because they don’t know—is how investors will react after the fact.

The consensus forecast is for a 2.5% year-on-year increase in the headline rate (including food and energy prices) and a 0.5% increase on the month.

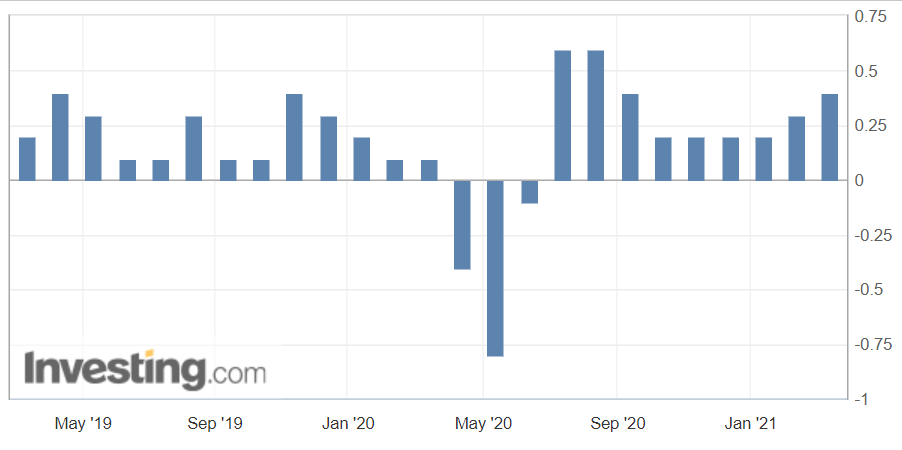

One month does not a trend make, and the so-called base effect will assert itself as the year-on-year progress reflects depressed prices from the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic.

Federal Reserve policymakers have repeatedly said they expect an increase in inflation but that it will be temporary and won’t prompt action on their part. In any case, the Fed prefers the personal consumption expenditures price index for tracking inflation, and that runs lower than the CPI.

But skittish investors may overreact if CPI inflation comes in significantly higher than the forecast. Their reaction would take the form of selling U.S. Treasuries, pushing up yields in anticipation of a trend in higher inflation and earlier-than-expected Fed action to raise rates.

Some analysts believe that CPI increases are already priced into the market as yields on the benchmark 10-year Treasury nearly doubled at one point from the beginning of the year.

U.S. producer prices rose more sharply than expected in March, according to data from the Labor Department, showing a gain of 4.2% on the year instead of the 3.8% forecast and 2.8% year-on-year in February. The producer price index rose a full 1% on the month instead of the 0.5% forecast. Treasury yields spiked briefly but then fell back.

Those analysts looking for increasing inflation say it may not become apparent until next month when April data is published. Two months of sharp increases would start to look like a trend. This could be particularly true if month-on-month increases run higher than forecast.

The Treasury Department has scheduled auctions for $271 billion this week after pausing issuance for a couple of weeks, with $120 billion in coupon-bearing securities. Monday’s auctions of $58 billion in three-year notes and $38 billion in 10-year notes went smoothly, and $24 billion of 30-year bonds are up today [Tuesday].

Fed policymakers are blaming the fiscal stimulus and the added bond issuance for what they call rising term premiums, and it is these that are pushing up yields— not any fundamental change in inflation expectations or anticipation of Fed tightening. This is one of the insights from the minutes of the mid-March Federal Open Market Committee meeting, which were released last week.

The New York Fed, which handles market operations for the central bank, has hinted it will make some “minor technical adjustments” to its purchase sectors, leading some analysts to expect the Fed will increase its portion of seven to 20-year bonds to account for changes in the weight of the market due to the heavy issuance schedule. This would be offset by reductions at the shorter end.

Investors will be paying close attention to the release this week of the Fed’s schedule of bond purchases for indications of this adjustment.