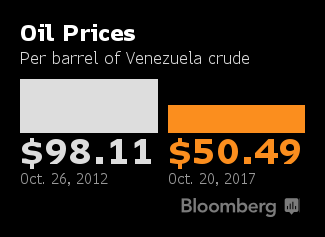

(Bloomberg) -- Ever since the price of oil collapsed in mid-2014, there’s been a broad consensus among the bond-market crowd that Venezuela was going to default. Not immediately, they said, but at some point down the road.

Three years on, that time may have arrived. On Friday, the government-run oil giant PDVSA owes $985 million. Six days later, it’s on the hook for another $1.2 billion. Not only is that a daunting sum for a country whose foreign-currency reserves recently dipped below $10 billion for the first time in 15 years, but it figures to be a logistical nightmare too.

Increasingly isolated by U.S. financial sanctions that have spooked banks and other intermediaries in the bond payment chain, Venezuela has already fallen behind on interest payments worth $350 million that were due earlier this month. Those payments had a grace period -- a buffer of sorts that gives the country an additional 30 days to work out the technical glitches and deliver the cash. The principal portions of the payments owed over the next two weeks contain no such language. Miss the due date and bondholders can cry default. Prices on the notes due Nov. 2 acutely reflect those risks: They’re at just 93 cents on the dollar.

“This is Venezuela -- they’re very disorganized with these types of things,” said Alejandro Grisanti, the director of the Caracas-based research firm Ecoanalitica. “Every day, it’s harder for them to pay.”

A default would be a painful end to what has proven one of the more profitable, and strange, trades in emerging markets over the past two decades. While the plunge in oil prices deepened an economic collapse and triggered a humanitarian crisis unprecedented in the nation’s history, President Nicolas Maduro, like his predecessor and socialist mentor Hugo Chavez, has been determined to meet all foreign bond payments.

Why Venezuela Struggles So Hard to Avoid Default: QuickTake Q&A

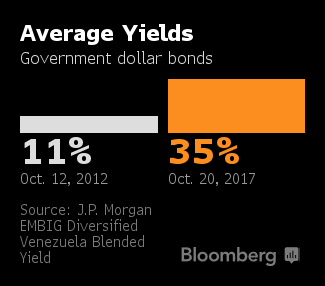

And because yields on the bonds have been so high, the returns have been eye-catching: over 9 percent per year on average over the past 20 years. This combination -- outsize profits for Wall Street traders and shortages of food and medicine for Venezuelans back on the ground -- has been so jarring that it even led to the coining of a new term for the nation’s debt: hunger bonds.

The fine print on these next two principal payments puts Venezuela in a tricky spot. If PDVSA were to deliver the funds even one day late, investors can rally together to demand the immediate payment of the rest of the money they’re owed. (Lacking the funds to pay back all the debt at once, Venezuela would likely look to enter into restructuring talks with creditors -- a step that’s complicated by the sanctions.)

It isn’t clear, to be sure, that investors would want to

immediately escalate the situation. For one, getting 100 cents on the dollar a few days, or even weeks, late would be much less painful than enduring legal battles and restructuring negotiations that are likely to drag on for months, if not years. What’s more, analysts estimate that creditors could get as little as 30 cents on the dollar in the end. There’s broad reluctance to unnecessarily upset the gravy train, even if it’s showing signs of tipping over.

“It is better for bondholders to get cash, even late,” said Lutz Roehmeyer, who helps oversee about $14 billion at Landesbank Berlin Investment GmbH, the 13th-largest reported holder of PDVSA’s 2017 bonds. “Most of the bonds are with U.S. funds or local investors who won’t have an incentive to trigger a default.”

Investors in the credit-default swaps market, though, have a different set of incentives. They would seek to get ISDA, the ruling body in the swaps market, to declare a default, which would trigger payouts on the contracts.

Foreign Reserves

Venezuela could still also make the payments on time. While $10 billion in foreign reserves isn’t much for a country that now owes some $140 billion to foreign creditors, it’s still enough to pay the bills for a while.

And the Maduro government has surprised the bond market before, making payments the past couple years that many traders had anticipated would be missed. Some of those now betting that these next two payments will also be made actually point to the $350 million currently overdue on the other notes as an encouraging sign. Those arrears indicate, they contend, that officials are prioritizing the payment of bonds with no grace period at the expense of those they can put off without penalty.

Even if Venezuela can make the payments due this year, investors say that, unless oil prices stage some sort of miraculous comeback, they still see default as an inevitable outcome. Credit-default swaps show they’re pricing in a 75 percent chance of a PDVSA default in the next 12 months and 99 percent in the next five years.

“When oil prices were high, they threw the best parties” and “put none of the money away in the bank,” said Ray Zucaro, the chief investment officer at Miami-based RVX Asset Management, which holds PDVSA securities. “So when the spigot turned off with oil prices, it left them in a bind because they had spent way too much, they had borrowed way too much.”