(Bloomberg View) -- It's a new era for the Fed. We're a decade past the 2008 crisis, and we're at the dawn of a new Federal Reserve chair's reign. One could reasonably expect central bankers to step away from their clever art of forward guidance -- the panoply of projections, dots and qualifiers that have come to clutter their communications. A reasonable expectation, but wrong. They are mostly here to stay.

Once secretive, hugely influential institutions have become more open. Officials have become more predictable and have reduced volatility around decisions. The central banks themselves have used the guidance to steer expectations about the economy and, in so doing, to steer the economy itself.

While central banks have used forms of forward guidance for a while, the halcyon days have unquestionably been in the post-2008 era. Despite the public good, it has been a bit of pain for officials, especially when projections don't pan out.

The topic of forward guidance took up a good bit of oxygen at the American Economic Association's annual meeting in Philadelphia last weekend. Princeton University's Alan Blinder, himself a former Fed vice chair, told the conference that he and three co-authors polled almost 40 central bankers on how they thought monetary policy had evolved since the financial crisis. A stunning 59 percent said forward guidance will remain a potential instrument of policy and a further 13 percent said it would remain, but in a modified form. Not one thought it should be relegated to the history books.

Some critics of modern forward guidance say that investors have become so addicted to information that they can't think for themselves (are you listening up in Canada?). Another concern is that all the voices become a cacophony -- adding noise rather than clarity. Both are fair points.

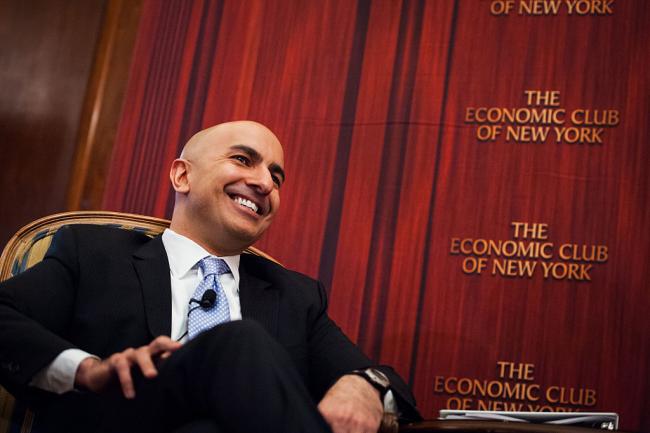

Those are problems that can and should be managed, according to Blinder, rather than eradicated with an end to forward guidance. He doesn't think the famous "dot plots" are particularly insightful, but he did suggest a tweak to Federal Open Market Committee statements. He illustrated the idea by proposing an alternative version of the third paragraph of the statement released by the FOMC after its December meeting, at which the Fed raised its benchmark rate by a quarter point and earned dissents from the Chicago Fed's Charles Evans and Neel Kashkari of Minneapolis.

Here's the paragraph released by the Fed:

In view of realized and expected labor market conditions and inflation, the Committee decided to raise the target range for the federal funds rate to 1-1/4 to 1‑1/2 percent. The stance of monetary policy remains accommodative, thereby supporting strong labor market conditions and a sustained return to 2 percent inflation.

And here's Blinder's alternative proposal:

In view of realized and expected labor market conditions and inflation, the Committee decided to raise the target range for the federal funds rate to 1-1/4 to 1-1/2 percent. Some members thought a tightening at this meeting was premature, given that inflation remains below 2 percent and shows no signs of rising. The majority, however, viewed the stance of monetary policy as still quite accommodative, and therefore supportive of strong labor market conditions, even with the higher funds rate range. Most also saw a sustained return to 2 percent inflation as likely, given the tightness of labor markets.

Now, that won't stop the competing statements, interviews and speeches that are likely to be deployed by dissenters in the future. But in the spirit of a problem to be managed, it's a decent start, especially considering there is so much information already out in the public domain.

Which brings us to why Blinder and others say central banks should keep trying -- but should expect to fail. They may feel that the public cares deeply about what they say. The investment community and bank managers certainly do. The broader public doesn't care much at all.

The risk, said Ricardo Reis of the London School of Economics, is that by trying to make themselves familiar to the broader public, they end up venturing into areas where they have no control over the outcome and perhaps not a lot of expertise. Recent forays into education by at least one FOMC member come to my mind. So when outcomes aren't met, it's all too easy for people to say "look, see, they failed again."

Forward guidance isn't something you can just dip into and then stop doing. Once that genie is out, it's out. That is mostly for the good, but officials ought to really think twice before dramatically expanding the scope of their guidance.

This column does not necessarily reflect the opinion of the editorial board or Bloomberg LP and its owners.

Daniel Moss writes and edits articles on economics for Bloomberg View. Previously he was executive editor of Bloomberg News for global economics, and has led teams in Asia, Europe and North America.