(Bloomberg Gadfly) -- It seems as if the Federal Reserve's interest rate is the one that is stuck.

The Fed on Wednesday left its benchmark overnight lending rate in a 1.25 percent to 1.5 percent target range. Chair Janet Yellen, in her last rate-setting meeting, went out quietly, or perhaps true to form. Much of the commentary around her exit has been praise that she resisted raising rates further even as critics said they needed to go higher. More important, despite what President Donald Trump calls the largest tax cut in history, and record highs for the equity markets, the Fed gave only a conflicting indication about how fast it will raise rates this year. As Bloomberg News noted, the Fed added "further" twice to its previous language about future rate increases in its statement. But the Fed also repeated language that said “near-term risks to the economic outlook appear roughly balanced.” Many had thought the Fed might shift the statement to say that inflation and too much growth might be more of a risk than the opposite.

Jerome Powell, the incoming Fed chairman, inherits the hefty challenge and faces a significant change that could reverberate through financial markets.

For much of the past few years, it has been the 10-year Treasury rate that has been stuck, and a concern. Interest rates are supposed to move together. That's one of the signs of a healthy economy. When short-term rates go up, long-term ones tend to follow, or are expected to. But that hasn't been happening lately.

As the Fed has raised interest rates -- three times last year, and five since late 2015 -- the 10-year rate has remained stubbornly stuck. The bonds were yielding 2.3 percent in late 2015 and just over 2 percent as recently as last September. And so there were a lot of discussions about how the financial crisis, globalization or the lack of innovation may have permanently damaged the U.S.'s long-term potential. Others argued that long-term rates weren't moving because technology had slayed inflation and also possibly the need for human labor, leaving many out of the workforce and again permanently damaging the long-term economic outlook.

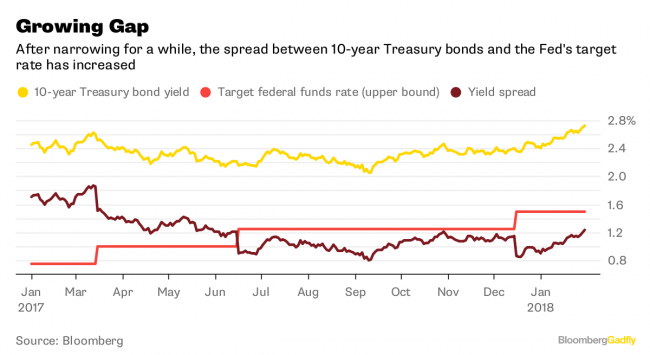

Recently, the opposite has been happening. The 10-year interest rate, now at 2.71 percent, is at a nearly four-year high. And while the yield is still relatively low historically, the pace of change in the bond market is increasing. Most important, 10-year Treasury yields didn't flinch on Wednesday, keeping their gains even after the mixed statement from the Fed on future rate increases. The spread between the Fed's overnight rate and the 10-year rate has increased to 1.23 percentage points, its largest difference since last May, after narrowing to as little as 0.8 percentage point.

That again can be seen as a good thing, that Yellen did her job and that Powell is being given a pretty good hand. An upward sloping yield curve is desirable, and this one is still relatively flat. So the rise in the 10-year curve could just indicate a pretty healthy economy.

But then again, GDP in the fourth quarter grew 2.6 percent, less than expected and historically weak, particularly with the unemployment rate at 4.1 percent, which in the past has translated to much higher growth. The yield on the 10-year Treasury is a function of long-term growth and long-term inflation expectation, as well as pretty much everything else you can think of. But mostly it's growth and inflation. So the other possibility is the 10-year yield is rising because inflation is about to spike, and what Powell is being handed is an economy with all the problems many people have been worrying about for the past few years plus the potential for runaway inflation.

That scenario has not played out yet even though many have been warning about higher inflation for years. Still, evidence is building that Powell will have to worry that it eventually will.

This column does not necessarily reflect the opinion of Bloomberg LP and its owners.

Stephen Gandel is a Bloomberg Gadfly columnist covering equity markets. He was previously a deputy digital editor for Fortune and an economics blogger at Time. He has also covered finance and the housing market.