Bowing to recent data, Federal Reserve Chairman Jerome Powell on Tuesday conceded that inflation progress has stalled and the case for rate cuts has weakened.

The Treasury market has been effectively making the same case for weeks, but when the top central banker says it out loud the crowd notices.

“More recent data shows solid growth and continued strength in the labor market, but also a lack of further progress so far this year on returning to our 2% inflation goal,” Powell said at a conference yesterday (Apr. 16).

“The recent data have clearly not given us greater confidence, and instead indicate that it’s likely to take longer than expected to achieve that confidence.”

The 10-year Treasury yield is paying attention and rose to 4.67%, the highest since Nov. 6. The question is whether the benchmark rate is still trading in a range. Or is it poised to take out its previous peak of roughly 5% that was set in October?

The case for expecting a trading range has taken a hit but it’s premature to write an obituary. As noted earlier this month, several ‘fair value’ models for the 10-year yield continue to suggest that a hefty market premium endures, which implies that the benchmark rate faces headwinds to ongoing increases.

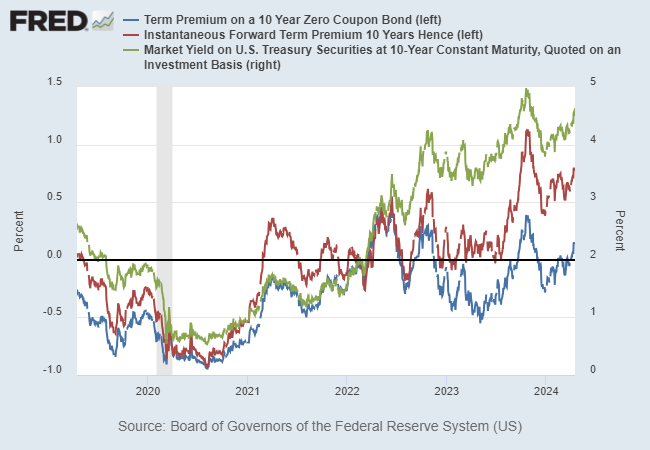

Another approach to putting the market-based 10-year yield into perspective is by comparing it with estimates of the term premium, or the compensation that investors demand for the risk that interest rates may change over a given bond maturity.

A higher (lower) term premium implies higher (lower) Treasury yields. The challenge is that term premia aren’t directly observable and so economists use models to estimate the data. It’s an inexact science, but one that’s still useful for developing additional context.

On that basis, it appears that the 10-year rate has risen more than is warranted by two estimates of term premia. The debate is whether the models are wrong or the Treasury market is overcompensating for expected risk.

I suspect that the conflict will be resolved, one way or the other, by incoming inflation data, which is at the heart of the recent rise in the 10-year rate. Sticky inflation numbers of late have convinced the crowd to demand a higher yield premium and until there’s convincing evidence otherwise the market will remain skeptical that disinflation endures.

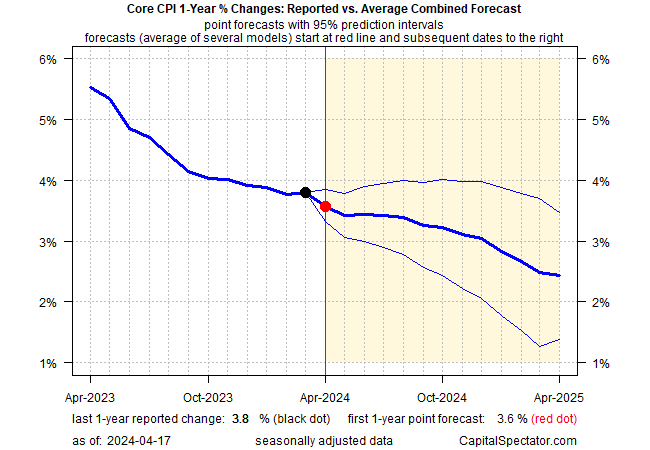

No one knows where inflation is headed, but my ensemble model for core consumer prices still points to ongoing disinflation. It could be wrong, of course, but this modeling’s track record is encouraging and so for now I still expect pricing pressure to ease, albeit at a slower pace than recently anticipated.

Assuming that the outlook is accurate, when will the Treasury market revise its expectations accordingly? For the moment, that realignment doesn’t appear imminent. Accurate or not, the crowd requires a higher inflation premium, even if that demand is headed for an attitude adjustment. As a result, it wouldn’t be surprising to see the 10-year yield move closer to the 5% mark in the weeks ahead.

What would drive the benchmark rate above that level? Tune in to next month’s release of April CPI for a possible answer.