Federal Reserve Chairman Jerome Powell was sort of bullish on the US economy, at least in the near term, and dovish on monetary policy in his remarks on Wednesday. Following the meeting of the Federal Open Market Committee, Powell emphasized the Fed’s “strong” commitment to keeping policy accommodative until economic recovery is well established.

But the lack of any specifics ended up disappointing investors, who had been expecting more detail—about anything. At the end of the day, the Fed really did nothing except extend its somewhat optimistic economic forecasts out to 2023.

The non-news cut short a stock market rally so that broader market benchmarks such as the S&P 500 and NASDAQ closed in minus while the 30-component Dow eked out a small gain.

Growth Forecasts More Optimisic, Unemployment Outlook Grimmer

The economy is rebounding more strongly than expected, Powell said, while adding the caveat that further progress will depend on the course of COVID-19 infections.

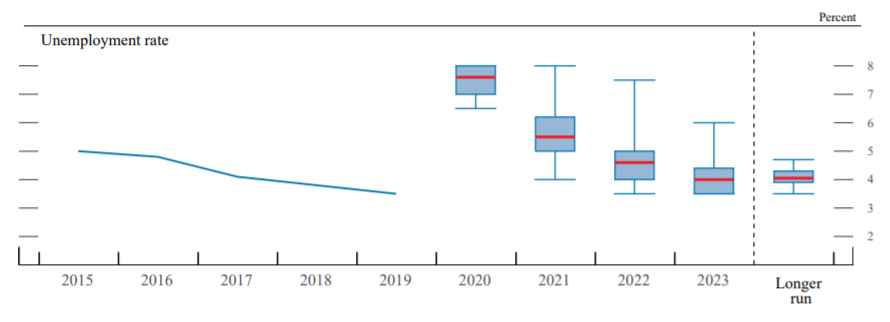

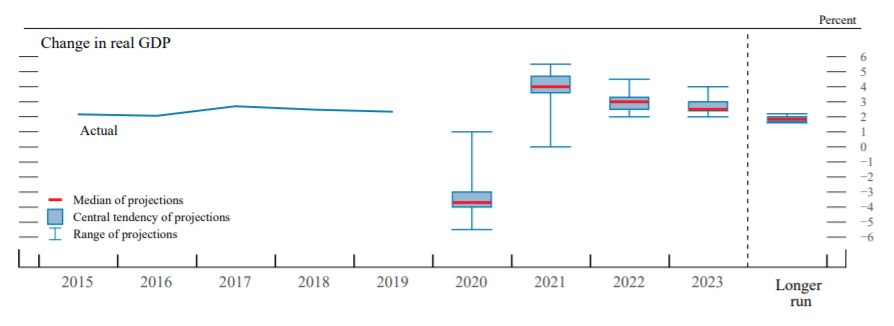

Policymakers revised their growth forecasts for this year upwards, and their unemployment forecasts downwards.

They now expect a contraction for all of 2020 of only 3.7%, compared with the 6.5% in June. They forecast unemployment at 7.6% for the year instead of 9.3% earlier.

However, the FOMC members lowered their growth forecasts for next year, to 4% from 5%, and took them down a notch for 2022 as well, to 3.0% from 3.5%.

For 2023, growth is projected to subside even further, to 2.5%, before hitting what the Fed thinks will be longer-run growth of 1.9%. Not a great trajectory.

And sectors that rely on bringing together large groups of people—airlines, travel, hotels, entertainment—will recover much more slowly, Powell said.

He affirmed that the Fed won’t be raising rates in the foreseeable future, as FOMC members projected them at near-zero through 2023.

He was vague, however, about the Fed’s asset purchases, saying only that they would continue at least at the current pace of $80 billion in Treasuries and $40 billion in mortgage bonds a month. Investors had hoped for some indication that those purchases would shift to longer-dated securities or some forward guidance about what would cause them to change.

The FOMC statement was altered from the late-July version to reflect the Fed’s new strategy of aiming for inflation to run above its 2% target in order to average out at 2% over time. The Fed will maintain its current policies until “inflation has risen to 2% and is on track to moderately exceed 2% for some time.”

For Powell, “these changes clarify our strong commitment over a longer time horizon.” The projections by the FOMC members, in fact, put inflation at 2.0% only in 2023, if then. The range of forecasts went as low as 1.7% for the personal consumption expenditure index the Fed uses to track inflation. Policymakers only got to 2% inflation by extending their projections to 2023 from 2022 in the previous round.

The growth forecasts, Powell made clear, depend on further fiscal stimulus, even though Democrats and Republicans in Congress remain deadlocked on the amount and form of government relief.

There were some quibbles, as Minneapolis Fed chief Neel Kashkari dissented from the consensus statement because he favors guidance that rates would be kept near zero until inflation reached 2% “on a sustained basis.” Dallas Fed president Robert Kaplan basically agreed with the goals of the statement but would like for the FOMC to have greater flexibility on rates.