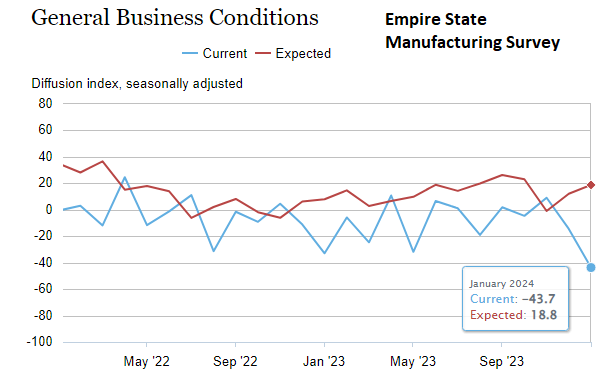

The sharp drop in the New York Federal Reserve’s Empire State business-conditions index in January triggered a wave of warnings.

Soon after this monthly survey data was released yesterday (Jan. 16), social media and beyond lit up, warning that this was a smoking gun for the US economy’s imminent descent into recession, assuming output hadn’t already turned negative.

But like most single-indicator releases, the crowd rushed to judgment and allowed the headlines du jour to overwhelm more thoughtful analysis.

The NY Fed Manufacturing Index, as it’s popularly known, is prized as an early read each month on the manufacturing sector.

The sight of this index dropping deep into negative terrain for January – the lowest reading since 2020, when the pandemic was raging – convinced some observers to warn that the jig is up and a US recession has arrived or is near.

Maybe, but it’s hard to make a high-confidence call based on one indicator, much less one regional manufacturing indicator that draws on survey data from manufacturing executives in the NY Fed’s district.

On that note, keep in mind that these same executives have become increasingly upbeat about the future (red line in the chart below).

In fact, the NY Fed Manufacturing data is reaffirming old news. The manufacturing sector of the US overall has been in a slump for more than a year.

The ISM Manufacturing Index in December marked the 14th straight month of contraction. A competing index reflects a similar condition.

“US manufacturers ended the year on a sour note,” says Chris Williamson, Chief Business Economist at S&P Global (NYSE:SPGI) Market Intelligence.

The question is whether manufacturing carries the same weight for analyzing the US business cycle relative to years earlier.

Minds will differ, but there’s no doubt that pre-pandemic assumptions about the recession signals have had a rough ride in the past few years as the economy has transitioned after an unusual and unprecedented run of macro activity and government intervention.

Indeed, 2023 has been a master class in reminding analysts that the business cycle has evolved in surprising ways. Notably, the dark forecasts of a year ago turned out to be dead wrong.

There’s no way to know for sure if an NBER-defined contraction is finally here, but there are productive and relatively reliable metrics to monitor that go well beyond cherry-picking a few indicators.

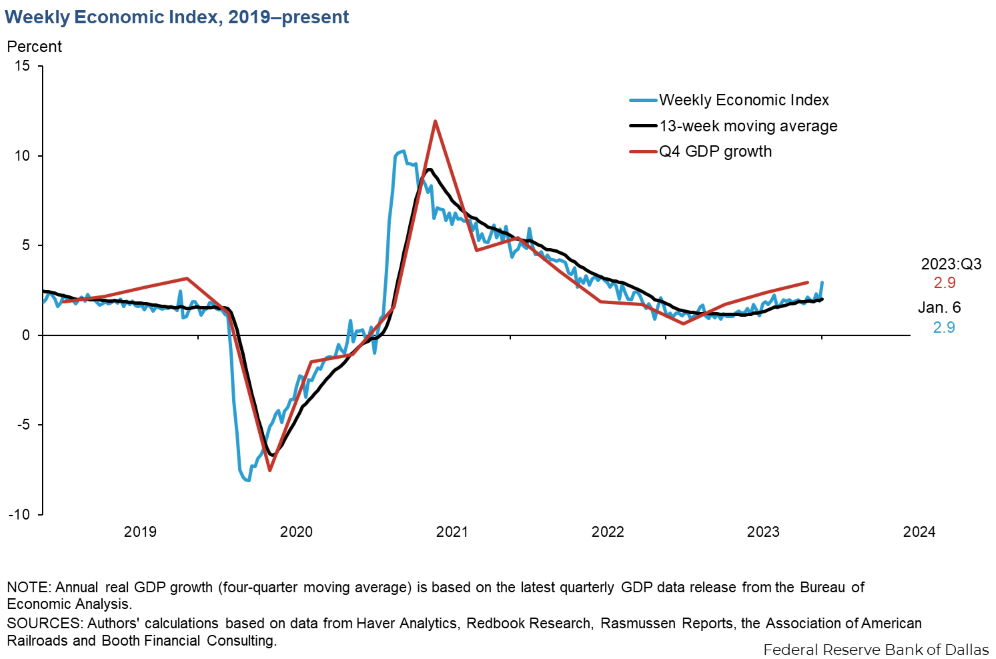

Consider, for instance, another index designed by the New York Fed (and now updated by the Dallas Fed): the Weekly Economic Index (WEI).

This multi-factor benchmark that tracks a range of US indicators rose to a 16-month high for the week through Jan. 6.

Another real-time, multi-factor business-cycle indicator – the ADS Index, published by the Philly Fed — tells a similar story, posting moderately strong readings over the past month.

Based on these two indicators, the debate could plausibly focus on the question: Is US economic activity strengthening in early 2024?

Maybe not, but if we’re interested in high-confidence estimates of how the economy is evolving it’s still clear that recession risk is low.

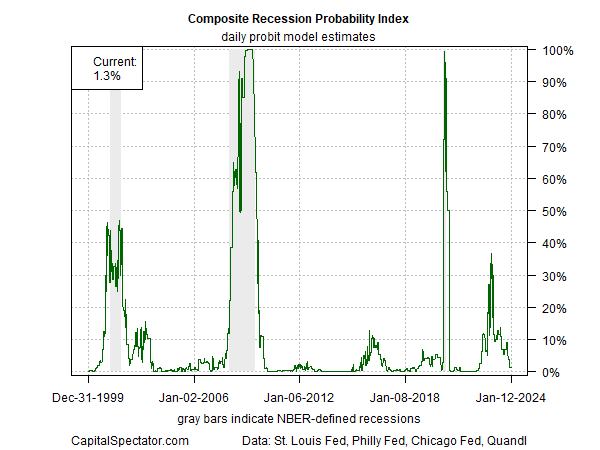

As detailed in this week’s issue of The US Business Cycle Risk Report (BCRR), the real-time signals across a wide array of indicators continue to reflect a low probability that an NBER-defined recession – the gold standard for marking US business cycle dates — has started or is imminent.

As shown below, BCRR’s flagship indicator, which aggregates several public and proprietary business-cycle indexes, currently estimates a roughly 1% probability that economic activity is negative, as of Jan. 12. (For details on how the chart below is constructed, see p. for this sample issue of BCRR).

The near-term future suggests more of the same, based on a set of proprietary analytics that currently estimate business-cycle conditions through February.

Generating forward estimates via a short forward window, via 14 key economic and financial indicators, has a solid record of anticipating the degree of strength/weakness of the business cycle (see p. 2 in BCRR for details).

Does the NY Fed’s Manufacturing Index – or weak manufacturing activity generally – supersede broadly defined business-cycle indicators?

Maybe, but there’s no way of knowing that in real-time, especially in the post-pandemic era – assuming you’re trying to estimate business-cycle conditions with a high degree of confidence.

As Ian Shepherdson, chief economist at Pantheon Macroeconomics, says:

"The sharp drop in the New York Fed Manufacturing Index is “Startling but not definitive.

The plunge in the headline index will no doubt generate alarmist headlines, but remember that the month-to-month swings in the regional Fed manufacturing surveys are mostly noise.”