An IPO, or Initial Public Offering, is the first time shares of a formerly privately-held company are sold to the general public via equity markets. As a rule, private companies go public in order to raise capital via the sale of shares, in order to obtain funds for development and growth.

To be clear, privately-held companies do have shareholders, but ownership is limited to founders, key executives and other company insiders as well as select stakeholders who've had some critical impact on the company's founding or growth, such as early stage angel or VC investors. The general public is not allowed to own shares in a private company, which leaves individual investors on the sidelines even if they're interested in obtaining an ownership stake during the early stages of promising start-ups that have the obvious potential to become future industry leaders, such as Uber (NYSE:UBER) was a few years ago and AirBnB is today.

Understandably, when a highly regarded privately-held company goes public, it can garner a lot of attention which generates excitement among investors, often and especially among retail investors. But should a retail investor actually buy in when a stock IPOs?

Evaluating An IPO's Merits Can Be Hard

Government regulations require publicly traded companies to submit quarterly performance reports, called 10Qs. These are available to the public as well. Usually, investors interested in a particular company can find years’ worth of 10Q filings in order to research and analyze the merits of investing in a particular company. In many cases, S&P 500 and similar companies have data available from the past decade if not more.

Doing due diligence on an upcoming IPO is trickier and often more difficult. The only thing available to retail investors is the mandatory, pre-IPO S-1 filing the SEC demands from companies before it approves their offering.

Unfortunately, the information in an S-1 filing can be limited. Uber, for example, was founded in 2009 and went public in early May 2019. Though the company had been in business for about a decade, it’s S-1 filing covered only financial data from 2016 and forward. Retail investors thereby missed out on seven years of financial data which could have fleshed out and enhanced their analysis.

This underscores not only the difficulty of evaluating a company with only limited data, but also the information asymmetry that exists in the run-up to an IPO between retail investors versus insiders and well connected institutions who have significant money to invest. The insiders and well connected financial entities get face-to-face meetings with founders and access to financial information that's not available to the general public. Pre-IPO, retail investor are at a serious disadvantage.

As well, the roadshow that's often conducted ahead of an IPO, plus all the releases about the upcoming event—and the media coverage generated—has just one goal: to create buzz and drum up interest in the offering. Many retail investors end up not being able to separate the signal from the noise. Bullish appetite for shares expands while risks are obscured.

Access Can Be Difficult

When a company wishes to IPO it often employs an underwriter, frequently a high profile investment bank, such as Goldman Sachs or Morgan Stanley, which makes sure all the shares made available to the public are purchased (the bank buys all the float or regular shares), ensuring the target amount of capital the company intended to raise is met; they also later resell the stock to the market.

It's also worth noting that a Direct Listing—conducting an IPO without using an investment bank—is also possible. Spotify (NYSE:SPOT) and Slack (NYSE:SK) are two prominent examples of companies that opted for direct listings. This route to public markets can save a company millions of dollars in fees, but opens the stock up to more volatility once it starts trading since investment bank participation mitigates the share price fluctuations often seen during the early days of trade.

Institutions can buy in at the offering price, which is predetermined by the underwriter. This is the share price the media often touts before the first day of trade begins. Lyft (NASDAQ:LYFT), for example, IPO’d at $72 a share. But gaining access to the initial price is almost impossible for retail investors, especially when an IPO is highly anticipated. When institutions receive an allocation of shares at the IPO price for their customers, they're offered to VIPs and high net worth individuals first.

Therefore, the advertised price is almost never what a retail investor will pay, even if they buy shares as soon as the stock begins to trade. To return to the Lyft example, shares actually started trading at $87, 21% above the IPO price. A company is only as good as the price you pay for it. For retail investors, there's almost always a payment premium to getting in on the IPO action at the very start.

Initially, Performance Is Uneven...At Best

Taking on increased risk and uncertainty should be rewarded by big profits, but the reality is often different. During the past two years, for the most part, marquee IPOs haven’t outperformed the S&P 500.

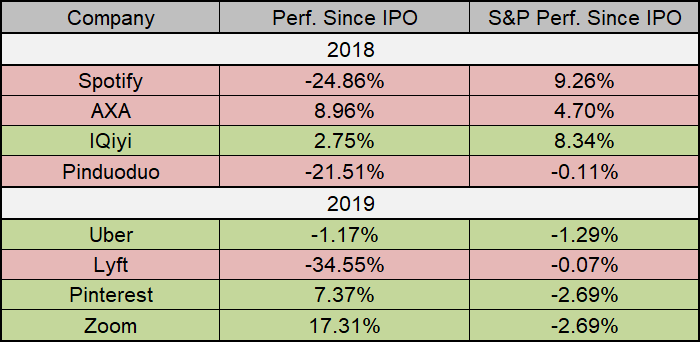

As mentioned above, since retail investors often have to pay a premium over the IPO price, we’ll measure performance based on a stock's first public market price, rather than from its ‘pre-sale’ price. The table below compares some of the most anticipated IPOs in 2018 and 2019.

The top of the table includes 2018's big IPOs: Spotify, AXA (OTC:AXAHY), iQIYI (NASDAQ:IQ), and Pinduoduo (NASDAQ:PDD). The bottom highlights the performance of the most anticipated 2019 IPOs so far, including Uber, Lyft, Zoom Technologies (OTC:ZOOM), and Pinterest (NYSE:PINS).

Clearly, it's been a mixed bag for the cream of the crop in 2018 and 2019. IPOs seemed to have fared better last year than this you so far. But keep in mind that it's also too early to provide a definitive verdict for 2019 IPOs.

Notice that relative to the S&P 500, the average overperformance of IPOs is 8.61%, while the average underperformance is -23.89%. Zoom’s IPO was the only one that significantly overperformed the broader market by 20%, whereas three—Spotify, Pinduoduo, and Lyft—underperformed by more than 20%.

This data doesn’t speak to the viability of investing in an IPO over the long-term, but it clearly shows that over the short haul, IPOs are not magic cash generators for retail investors as market mythology might have one believe. Rather, investing in an IPO requires tolerance for volatility, something retail investors often shy away from.

Conclusion

Obviously, the decision to get in on an IPO is entirely up to an investor. However, it's apparent the risks outweigh the lackluster performance over the short-term. The good news: with time, more information becomes available, true price discovery occurs and all investors are able to make smarter decisions.