It's time to talk about an unpleasant subject: Is depression possible? We aren't forecasting a depression, just worrying about one. And we suspect you are too.

We continue to believe that the economy will muddle down the middle between boom and bust. We expect that another drop in U.S. interest rates plus a lower US Dollar will induce other industrial countries to lower their interest rates. Then, we hope that a rebound in the industrial economies will eliminate the global glut of commodities, products, and labor.

This would relieve the deflationary pressures that are behind the international debt crisis. Growth in the industrialized world would stimulate the exports of debt-ridden nations. Worldwide competition and ample productive capacity should keep a lid on inflation. Policymakers could concentrate on promoting growth. This scenario is bullish for both bonds and stocks.

Sound too good to be true? Maybe so. But this is the scenario we are rooting for. We admit that a lot has to go right for it to work. Unfortunately, a lot is going wrong: commodity prices are falling; debtors are resisting austerity programs; agriculture is in a depression; the industry is in a recession; nonperforming loans are increasing; banks are failing; the trade deficit is widening; protectionism is gaining support; fiscal policy is gridlocked; and the Fed is in a box.

These are not the sort of problems we associate with the garden-variety postwar business cycle. Rather, they are very reminiscent of the events that triggered or exacerbated the first phase of the Great Depression from 1929 to 1933. The parallels are becoming obvious to all. With increasing frequency, clients are asking us to put a probability on another depression.[1] A few tell us they believe that we are already in the initial stage of depression.

Is a depression possible? How different is the current economic situation from that of the Great Depression? Upon reviewing the economic events of 1929 to 1933, we discovered a number of disturbing similarities. And the differences are even more disturbing![2] Yet, on balance, we conclude that a rerun of the 1930s is not very likely, but it is a risk if trade protectionists have their way.

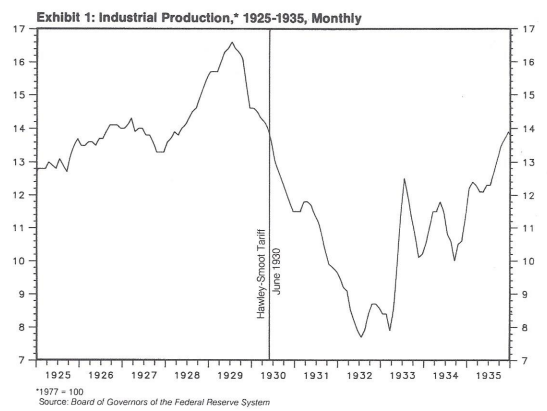

In our opinion, the single most catastrophic cause of the Great Depression was the Smoot-Hawley Tariff of June 1930—not the stock market crash of October 1929, not the collapse of the Austrian Kreditanstalt Bank in May 1931, not the sharp increase in the Fed's discount rate during October 1931, not the tax increase of 1932, not the subsequent bank failures or collapse of the money stock. All these events contributed to the economic explosion, but the detonator was the tariff.[3] That's confirmed by the collapse in industrial production immediately after the tariff was enacted (Exhibit 1).

Today, protectionist sentiments are spreading at an alarming rate. U.S. legislators have introduced more than 300 protectionist bills. The most sweeping proposal yet has come from the Democrats—the Trade Emergency and Export Promotion Act of 1985. It was introduced in the Senate during July by Lloyd Bentsen of Texas and in the House by Dan Rostenkowski of Illinois and Richard Gephardt of Missouri. The bill, which would impose a 25% tax on all imports from Japan, South Korea, Taiwan, and Brazil, is given a good chance of passage in the House when Congress reconvenes in September. Congress is also considering a bill that would impose stiff textile quotas on 11 of the United States' most important Asian trading partners. The bill should pass easily in the House this fall since it has 291 cosponsors.

Congress may force the hand of the Administration on Canadian lumber exports, which U.S. companies charge are unfairly subsidized because the Canadian government collects low cutting fees on public land. Oregon Senator Bob Packwood, chairman of the Senate Finance Committee, may give the President an ultimatum: Either take action to end the lumber crisis or Packwood will throw his support to a pending bill that the administration opposes, one that would roll back textile imports.

In the Reagan administration, free traders are losing ground to "realists" who argue that the President must move toward a more aggressive international trade policy to try to forestall passage of far-reaching protectionist legislation in Congress.[4]

If passed, such legislation could reduce world trade. The U.S. industrial recession and agricultural depression could worsen. International debtors could be forced to default. The crisis in the banking system might become unmanageable. This was the way the dominoes fell during the Great Depression.

But wouldn't the Federal Reserve avert such a calamitous chain of events by lowering interest rates? For several reasons, we doubt it:

- 1. During October 1931, following the sterling crisis, foreign investors lost their confidence in the dollar and demanded gold in exchange for the U.S. currency. To stop the gold outflow, the Fed raised interest rates. This move calmed the external crisis, but intensified the internal crisis as another wave of banks suspended operations. Again, to halt a run on the dollar, the Fed raised interest rates during February 1933.

- 2. In 1985, the Fed resisted lowering interest rates more aggressively, fearing that foreigners then might sell dollars and withhold capital needed to finance the huge federal deficit.

- 3. Moreover, the Fed is so worried about reviving actual and expected inflation that interest rates are never cut unless there is unambiguous justification for such a policy move, such as falling commodity prices and sluggish economic activity—they're deemed sufficient cause.

But if commodity price deflation precedes a cut in the discount rate, is the Fed really easing? It wouldn’t feel so to a Latin American country or Iowa farmer with a lot of debt. That's because the drop in their interest costs is offset by a fall in their commodity revenues. So on balance, they are still in trouble even though the Fed has "eased."

During most of the 1970s, the Fed erred on the side of inflation. More often than not, the Fed tightened too little, too late. Now, we are concerned that the Fed may be easing too little, too late.[5]

So much for the disturbing similarities between the 1930s and now. But the differences are also disturbing!

For example, the Smoot-Hawley Tariff was imposed on a U.S. economy that enjoyed a trade surplus with the rest of the world. Today, the U.S. is running huge trade deficits. As a result, protectionism probably has more grassroots support now than during 1929 and 1930.

During 1932, President Hoover raised taxes to pay for the increase in public works spending and therefore to balance the federal budget. Today, the federal deficit is so huge that there is no room for another New Deal. Economists are calling for tax increases, not to lower the deficit but to keep it from swelling above $200 billion.

Did The Great Crash Cause The Great Depression?

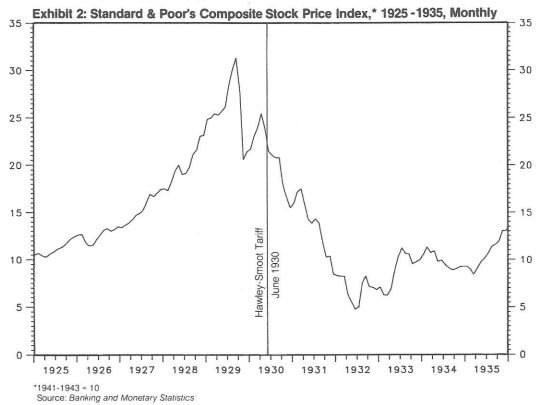

S&P Composite (1941-1943 = 10) peaked at 31.30 in September 1929 (Exhibit 2). The so-called Great Crash pushed this index down 34.2% by November. But by April 1930, the index recovered to 25.46, 18.7% below the September peak—and, it was unchanged from the year-earlier level! In other words, anyone who bought a diversified selection of stocks during April 1929 would have experienced no net change in the value of their portfolio by April 1930. But what a roller coaster ride it would have been!

Industrial production peaked in July 1929 after rising 25% over the previous 19 months (Exhibit 1 above). Over this same period, stock prices had more than doubled. Industrial production also recovered in early 1930 and then crashed when the Smoot-Hawley Tariff was enacted.

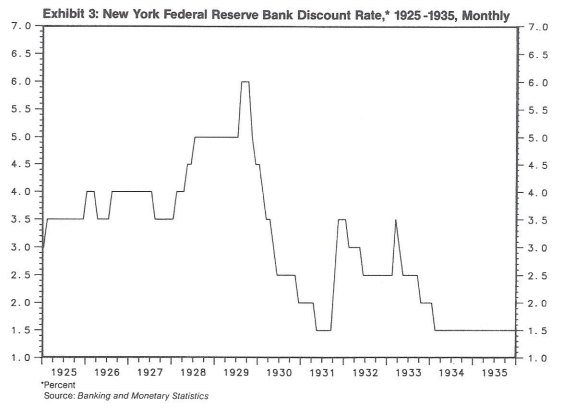

At the beginning of 1928, the Federal Reserve System began to operate against "excessive speculation" by raising interest rates. The discount rate was increased in four steps from 3.5% during January 1928 to 6.0% during August 1929 (Exhibit 3).

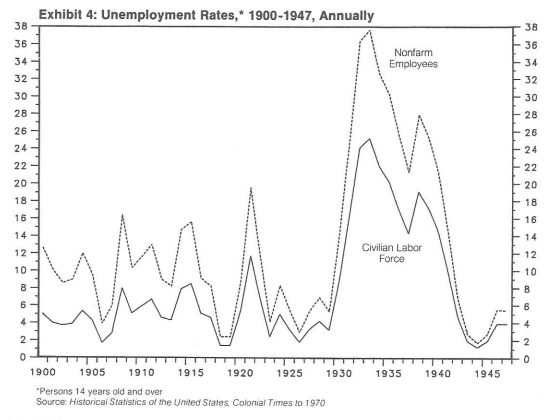

By the autumn of 1929, both industrial production and construction were declining rapidly. By June 1930, output had fallen back to where it had been at the start of 1928. The unemployment rate for nonfarm employees rose from 5.3% in 1929 to 14.2% in 1930 (Exhibit 4).

The Federal Reserve System responded to the decline in economic activity by lowering the discount rate from 6.0% during October 1929 to 2.5% during June 1930 (Exhibit 3 above). But industrial production and stock prices did not respond; instead, they collapsed. The unemployment rate for nonfarm employees soared to 25.2% in 1931 and 36.3% in 1932.

Why didn't lower interest rates revive the economy? How did the recession of 1929-1930 turn into the Great Depression of the 1930s?

The prosperity of the 1920s largely reflected the rapid expansion of new industries. These included automobiles, radios, household appliances, chemicals, petroleum products, and public utilities. But many industries did not participate in the boom of the 1920s. Among the distressed industries were bituminous coal, textiles, shoes, railroads, shipping, and agriculture.

The economic downturn of 1929-1930 created near-depression conditions for some of these industries. Political pressures for protectionism had been rising throughout the 1920s. These pressures culminated in the passage of the Smoot-Hawley Tariff in June 1930.[6]

The tariff was the Great Depression’s triggering event: Within two years of its passage—i.e., from June 1930 to June 1932—stock prices had crashed 78% and output had plummeted 42%.

The Smoot-Hawley Tariff

During the Presidential election campaign of 1928, Herbert Hoover promised American farmers that he would support a farm relief program and "limited" upward revisions of farm tariffs.[7] Hoover and the Republicans won by a landslide thanks, in part, to the farm vote. One of Hoover's first acts as President was to call Congress into special session in March 1929 to enact farm relief legislation and to raise tariffs.

Farm prices had declined during the 1920s in response to a large increase in the supply of agricultural goods. Non-European producers expanded during the interruption of European production caused by World War I. Once the war ended, competition intensified, and governments attempted to support prices by accumulating large stocks of agricultural commodities.

The U.S. balance of trade of farm products, which was positive until 1922, turned negative for the rest of the 1920s except in 1925. Farm exports as a percentage of farm income fell from 27.2% in 1919-1921 to 20.3% in 1922-1925 to 16.7% in 1926-1929.

Thanks to their over-representation in the U.S. Congress, farmers were able to press for very strong action. Even though the United States was urbanizing rapidly between 1910 and 1930, no reapportionment of representatives to the U.S. Congress was made after the census of 1920. As a consequence, Congress was heavily biased toward rural interests.

On June 15, 1929, Congress passed the Agricultural Marketing Act, which was a farm relief program. It took another year before Congress could compromise on the tariff issue. On May 7, 1929, Willis C. Hawley of Oregon introduced a tariff bill into the House. The White House lost control of the bill.[8] The measure ignored Hoover's specific limitations on tariff revision and provided for very extensive increases in tariff duties on almost every commodity that suffered from import competition. On May 24, the House passed the bill by a vote of 264 to 147. Only 12 Republicans voted against the bill, while only 20 Democrats from industrial areas were for it.

Reed Smoot of Utah introduced his version of the tariff bill to the Senate. It faced stiff opposition until it was finally passed by a vote of 53 to 31 on March 24, 1930.

The conference bill passed the Senate on June 13, 1930, by a vote of 44 to 42. The next day the House approved the bill by 222 to 153. In both houses, support for the Smoot-Hawley Tariff Bill came mostly from the industrial Northeast, which expected the most benefits. Ironically, the agricultural South and West did not favor the final version of this tariff that originally was supposed to benefit farmers.

Importers, industries with foreign markets, and 33 foreign governments warned President Hoover not to pass the tariff bill. In the May 5, 1930, issue of The Times, 1,028 American economists urged Congress and President Hoover not to raise tariffs (see Appendix). They predicted that other countries would inevitably retaliate by raising their tariffs.[9]

Hoover ignored the protests. He did not want to embarrass his party in a congressional election year. So he signed the bill on June 17, 1930. In its final version, the rates imposed by the Smoot-Hawley Tariff Act reached an all-time high in American tariff history.

International trade retaliation on a massive scale soon proved the economists right. Spain, Canada, Italy, Cuba, Mexico, France, Australia, and New Zealand quickly enacted new tariffs. On November 19, 1931, Britain imposed a 50% duty on 23 classes of goods. In July 1932, the Ottawa Conference forced the British Dominions to grant preferences to British goods. Germany resorted to import licensing and bilateral trading arrangements in November 1931. By 1936, 65% of French imports came under a quota system.

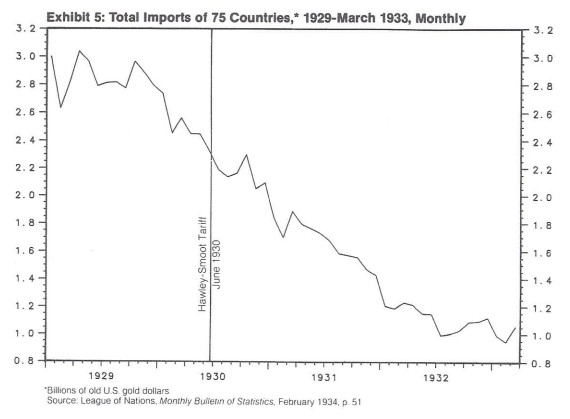

Trade became bilateral or regional within existing empires. Quotas, licensing agreements, and prohibitions complemented tariffs. By the mid-1930s, international trade largely had become barter trade. World trade collapsed (Exhibit 5).[10]

On March 2, 1934, President Roosevelt sent Congress a special message asking for authority to enter into Reciprocal Trade Agreements with foreign nations for the revival of world trade. He noted that measured in terms of the volume of goods in 1933, trade had been reduced by about 70% of its 1929 volume; measured in terms of dollars, it had fallen to 35%. "The drop in the foreign trade of the United States has been even sharper. Our exports in 1933 were but 52% of the 1929 volume, and 32% of the 1929 value."[11]

As a consequence of World War I, the United States had become the world's largest creditor nation. During the 1920s, the Federal Reserve sought to keep the world prosperous by deliberately inflating the money supply. Between June 1921 and July 1929, the total money supply (including savings and loan capital and life insurance reserves) increased at an average annual rate of 7.7%. The aim was to boost business activity directly through cheap credit and indirectly by encouraging foreigners to borrow in New York and spend the proceeds on American products.

The foreign lending boom started in 1921 and ended in late 1928. The foreign loans permitted European nations to maintain their unfavorable trade balances with the United States. But when the United States imposed the Smoot-Hawley Tariff, U.S. imports from abroad collapsed and the European trade deficits swelled. Many countries resorted to "defensive" tariffs in order to create export balances for debt payment, to check domestic price declines, and to stabilize their national economies.

Financial Panics

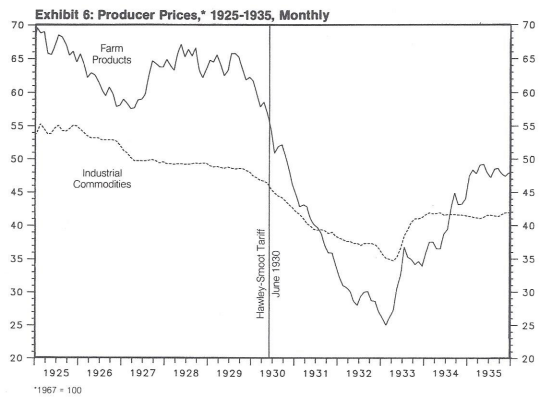

Trade protectionism set off a chain reaction of lethal financial crises. The producer price index for farm products fell sharply following the passage of the Smoot-Hawley Tariff in June 1930 (Exhibit 6).[12] By October, a crop of bank failures, starting from the agricultural areas, led to widespread attempts to convert demand and time deposits into currency.

This First Banking Crisis of the Great Depression was over by December. In fact, the economy started to show some signs of life in response to the sharp drop in interest rates. Industrial production rose slightly from January to April 1931 (Exhibit 1 above).

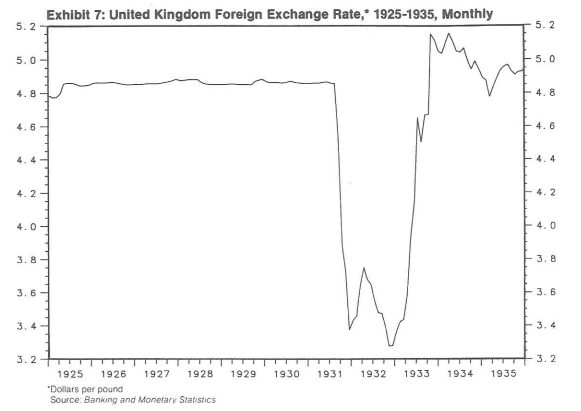

Unfortunately, a Second Banking Crisis started in March as the public resumed converting deposits into currency. This second monetary nightmare lasted for almost a year. Over this period: (1) The Kreditanstalt, Austria's largest private bank, failed in May; (2) Germany's banks closed on July 14 and 15; (3) Britain abandoned the gold standard on September 21; and (4) the Fed raised the discount rate on October 9.

The financial turmoil in Central Europe precipitated a run on sterling when British short-term assets were frozen in Germany. The Bank of England was forced to devalue the pound once its gold reserve had fallen to the point where it could no longer maintain the gold standard (Exhibit 7).

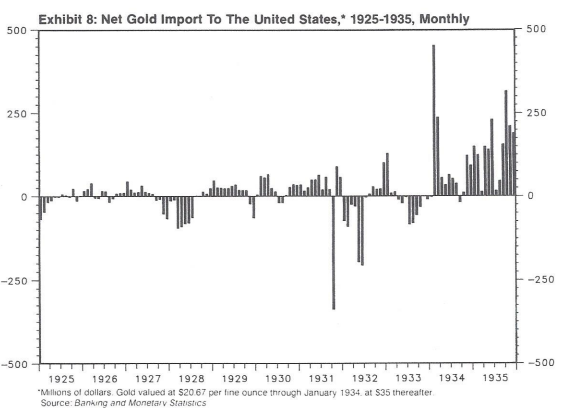

The international panic then spread to the United States, which also had a significant sum of short-term credits frozen in Germany. A foreign run on the dollar caused a 15% drop in the official gold reserve from mid-September to the end of October (Exhibit 8). (The gold drain temporarily ceased in November and December but resumed at the end of the year and continued with some interruption until June 1932.)

The Federal Reserve System reacted decisively and tragically. On October 9, the Federal Reserve Bank of New York raised its discount rate from 1½% to 2½% and to 3½% on October 16 (Exhibit 3 above).

According to economist Milton Friedman, this was "the sharpest rise within so brief a period in the whole history of the System, before or since." Why did the Fed do it? The rate increase was simply the orthodox response of the banking authorities to a gold drain under the gold standard mechanism.[13]

Monetary Collapse

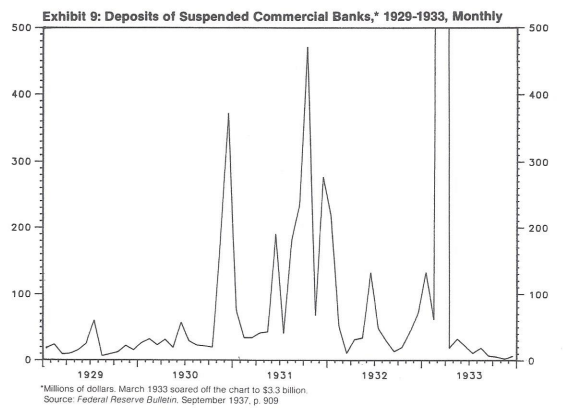

The Second Banking Crisis started in March 1931. Bank failures and runs on banks increased spectacularly following the discount rate hike (Exhibit 9). All told, in the six months from August 1931 through January 1932, 1,860 banks with collective deposits of $1,449 million suspended operations. Total deposits fell over the six-month period by nearly five times the deposits in suspended banks or by no less than 17% of the initial level of deposits in operating banks.

The flight to quality actually pushed the yield on three- to six-month Treasury notes and certificates below zero during October and November 1932! Government bond yields, however, rose for the first time since the start of the Great Depression because deposit losses forced banks to sell securities.

A preliminary memorandum for an Open Market Policy Conference during January 1932 noted that within "a period of a few months United States Government bonds have declined 10%; high-grade corporation bonds have declined 20%; and lower grade bonds have shown even larger declines."

The Fed responded to the banking crisis by cutting the discount rate to 3% in February 1932 from 3½% in January. It was cut again to 2½% during June. Also in April, under heavy congressional pressure, the Fed embarked on large-scale open market purchases.

Economic activity started to improve during mid-1932. The stock market started rising in June, wholesale prices in July, and industrial production in August. But the recovery was snuffed out late in 1932 by the Third Banking Crisis of the Great Depression. President Hoover was defeated for reelection in November. During the long interregnum until Franklin D. Roosevelt took office the following March 4, efforts to arrange cooperation between the incoming and outgoing presidents broke down.

Rumors that the incoming administration would devalue, led to a run on the dollar and sizable gold outflows early in 1933. For the second time during the depths of the Great Depression, the Fed responded (as it had in October 1931) by raising the discount rate in February 1933 to 3½% from 2½%.[14] A renewed wave of banking failures caused a number of states to declare bank holidays. By March 3, holidays had been declared in about half the states. On March 6, President Roosevelt closed all banks until March 9 and suspended gold redemption and gold shipments abroad.

Milton Friedman and Anna Schwartz in their 1963 study "A Monetary History of the United States, 1867-1960" concluded that the Federal Reserve caused the Great Depression. "An initial mild decline in the money stock from 1929 to 1930, accompanying a decline in Federal Reserve credit outstanding, was converted into a sharp decline by a wave of bank failures beginning in late 1930." The Fed failed to increase the monetary base enough to provide liquidity to the banking system. "The quantity of money... fell not because there were no willing borrowers—not because the horse would not drink." Instead, Friedman and Schwartz believe that by not increasing the monetary base, essentially holding back the supply of money, the Fed frustrated the demand for money.

We disagree. That was an ailing horse who would not drink. Once the forces of deflation were unleased by the Smoot-Hawley Tariff, monetary policy lost much of its influence on economic activity. Wholesale prices fell 9.4% in 1930, 15.5% in 1931, and 11.2% in 1932. With deflation this rampant, borrowers would have said that the real cost of borrowing was prohibitive even if the Fed had lowered the discount rate down to zero! To repeat: As a result of the deflation unleashed by the Smoot-Hawley Tariff, monetary policy lost much of its influence on economic activity.

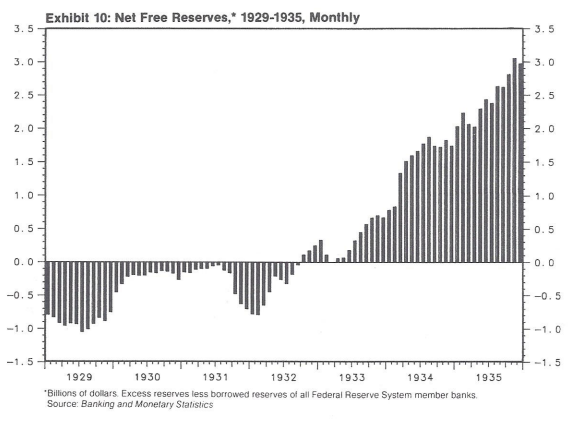

Each wave of the banking crisis increased the banking system's demand for excess reserves to meet deposit runs (Exhibit 10). Elmus Wicker, in his 1966 book "Federal Reserve Monetary Policy: 1917-1933," wrote: "The appetite for cash had apparently become so strong that the immediate impact of further open market purchases was to satisfy the banks' increased demands for cash without an expansion of bank credit." The Fed was pushing on a string because the economy was falling into a liquidity trap.

Could It Happen Again?

A rerun of the 1930s is not very likely, in our opinion. Pollster Lou Harris notes that the public is ambivalent on trade issues. Three-quarters of the public say they like access to low-cost foreign products. At the same time, three-quarters say there is unfair competition from abroad that is costing the U.S. jobs. On Capitol Hill, most representatives favor free trade but believe that no other countries are still practicing it.

Clearly, some import-restricting legislation will pass Congress this fall. And protectionist sentiment could be strong enough to override a presidential veto. But a repeat of the Smoot-Hawley disaster is not very likely.

Also, domestic banking and international debt problems are not causing financial panic and a monetary collapse. Recently, in Ohio and Maryland, runs on banks (which were covered by private deposit insurance) were contained and halted by requiring local depository institutions to apply for federal deposit insurance.

International debtors are resisting IMF-style austerity programs. However, the debtors have rejected the idea of walking away from their obligations and continue to work out rescheduling agreements with their creditors.

The Federal Reserve is likely to drop interest rates further if the forces of deflation continue to dampen economic growth. Unlike in the 1930s, domestic concerns should outweigh foreign exchange objectives in the conduct of Fed policy. Lower interest rates aren't likely to reaccelerate or reflate the economy, but they'll help to avert a recession. In other words, we should continue to muddle down the middle.

***

Notes

[1] During the first half of 1982, we received more attention than we deserved or desired by suggesting that the risk of a depression was 30% if the Fed remained committed to "knee-jerk monetarism" (see "The Cheerful Pessimist," Forbes, June 7,1982). The Fed was keeping interest rates high because M1 was growing too rapidly. We argued that the depression in the "rust bowl" and declining money velocity justified an aggressive move to lower interest rates. The Fed finally did ease during the summer when Mexico defaulted. We were bullish on bonds in June. We turned bullish on equities on August 16. Back then the Fed did avert a depression by cutting the discount rate from 12% to 8½% from July to December 1982.

[2] Greg A. Smith, Managing Director of Research at Prudential-Bache Securities, examined the parallels between the equity market today and the market's pattern in the late 1920s in "Could 1985 Be The Pivotal Year 1926 Was?," April 15, 1985.

[3] In his investigation of the causes of the Great Depression, Temin doesn't even mention the tariff. Neither do Friedman and Schwartz, who argue instead that the Federal Reserve was to blame. Saint-Etienne is one of the few analysts who characterize the tariff as an important contributor to the depression.

[4] The President reaffirmed his commitment to free trade on August 28, 1985, when he rejected the findings of the International Trade Commission and declined to grant import relief to the domestic shoe industry. This action has incited the protectionists in Congress to attach their import-restricting bills to a tough-to-veto measure, such as an increase in the debt ceiling or an omnibus appropriations bill.

[5] Testifying before the House Banking Committee on July 17, 1985, Fed Chairman Paul Volcker said, "The possibility at some point that sentiment toward the dollar could change adversely, with sharp repercussions in the exchange rate in a downward direction, poses the greatest potential threat to the progress we have made against inflation. Those risks would be compounded by excessive monetary and liquidity creation."

[6] Today's distressed industries include textiles, shoes, agriculture, mining, petroleum, steel, and commercial real estate. If the U.S. economy slips into a recession, the pressures for protectionism could be awesome.

[7] As economist Joseph Schumpeter put it, tariffs were "the household remedy" of the Republican Party.

[8] Today, the White House hopes to control the protectionist movement in Congress by filing complaints against foreign producers under a section of the 1974 Trade Act that allows sanctions ranging from quotas to embargoes against imports shown to damage U.S. business.

[9] In the June 23, 1985, issue of The New York Times, a two-page ad headlined "Budget Cuts Now. Then Tax Reform" was signed by 600 "Supporters of the Bipartisan Appeal on the Budget Crisis"-—a virtual Who's Who of the U.S. financial establishment. "The window of opportunity for decisive fiscal correction has almost closed....Our national economic future hangs in the balance.

[10] From 1925 to 1929, the volume of world trade increased by 20%. Over the same period, the price index of world traded goods fell by 12%. These two divergent trends point to an ongoing situation of oversupply and extreme competition in world markets. Today, global gluts are also putting tremendous deflationary pressures on the world economy and financial systems."

[11] On June 12, 1934, the Reciprocal Trade Agreement Program became law. It gave the President the power to negotiate tariff reductions with foreign nations over the next three years. This power was periodically renewed until it was replaced by the Trade Expansion Act of 1962. (See Ratner.)

[12] An ironic development since the tariff initially was intended to help farmers.

[13] Against the background of these facts. President Hoover decided to raise taxes. The increase proposed was a big one—about one-third as much as all existing taxes, enough to balance the fiscal 1933 budget The bill was enacted June 6. 1932 Hoover believed that a balanced budget was necessary "to reestablish confidence and thus restore the flow of credit which is the very basis of our economic life." It was a widely-held belief that "sound finance" was needed to keep interest rates from risıng even higher and to restore confidence in the dollar and in bank deposits. (See Stein. pp.31-38.) According to the Speaker of the House of Representatives, "At the end of my speech, I said: Now every man in this House that believes in levying a tax bill sufficient to sustain the American dollar. I want him to rise. Every one of the members rose. We did pass a tax bill and it saved the situation" (quoted in Yeager, p. 302)

[14] The New York Times described this increase as "a perfectly normal and customary expedient in a time of large gold withdrawals"—which is a revealing commentary on the state of economic thinking at the time. Both episodes involved preoccupation with gold reserves and with precautions actually or supposedly necessary to maintain the gold standard in the face of foreign drains.