In a November 19 post titled “Yardeni And The Long History of Stock Market Prediction Problems,” Lance Roberts, the Chief Investment Strategist for RIA Advisors, wrote that I am a permabull. The slant of his article was critical of both my upbeat Roaring 2020s forecast and my often optimistic outlook for the economy and stock market:

“In conclusion, while Yardeni’s optimistic forecast is enticing, several risks could derail this bullish outlook. First, historical precedents remind us that unforeseen economic downturns can reverse market momentum even during seemingly unstoppable growth. As noted, Yardeni made bullish forecasts previously, only for economic realities to undermine those projections.”

Am I a permabull? Guilty as charged! In response to the thought-provoking bearish views of the permabears, I try to provide some balance by examining what could go right. Often, I find that the permabears have missed something in their analyses. Since they accentuate the negatives, they often fail to see the positives or they put negative spins on what’s essentially positive. I rarely have anything to add to the bearish case because the bears’ analyses tend to be so comprehensive. So my attempts to provide balance often cause me to accentuate the positives while still acknowledging the negatives.

Hence, I am often called a permabull, which I take as a compliment. When I die, I would like my tombstone to state: “Ed Yardeni, 1950-2050. He was usually bullish and usually right!” While my optimism on the long-term outlooks for the US economy and stock market is often criticized, that’s all right by me because it’s often warranted: The US economy often grows at a solid pace, and the stock market has been on a bullish long-term uptrend as a result.

Consider the following:

(1) The past half-century has brought only six bear markets

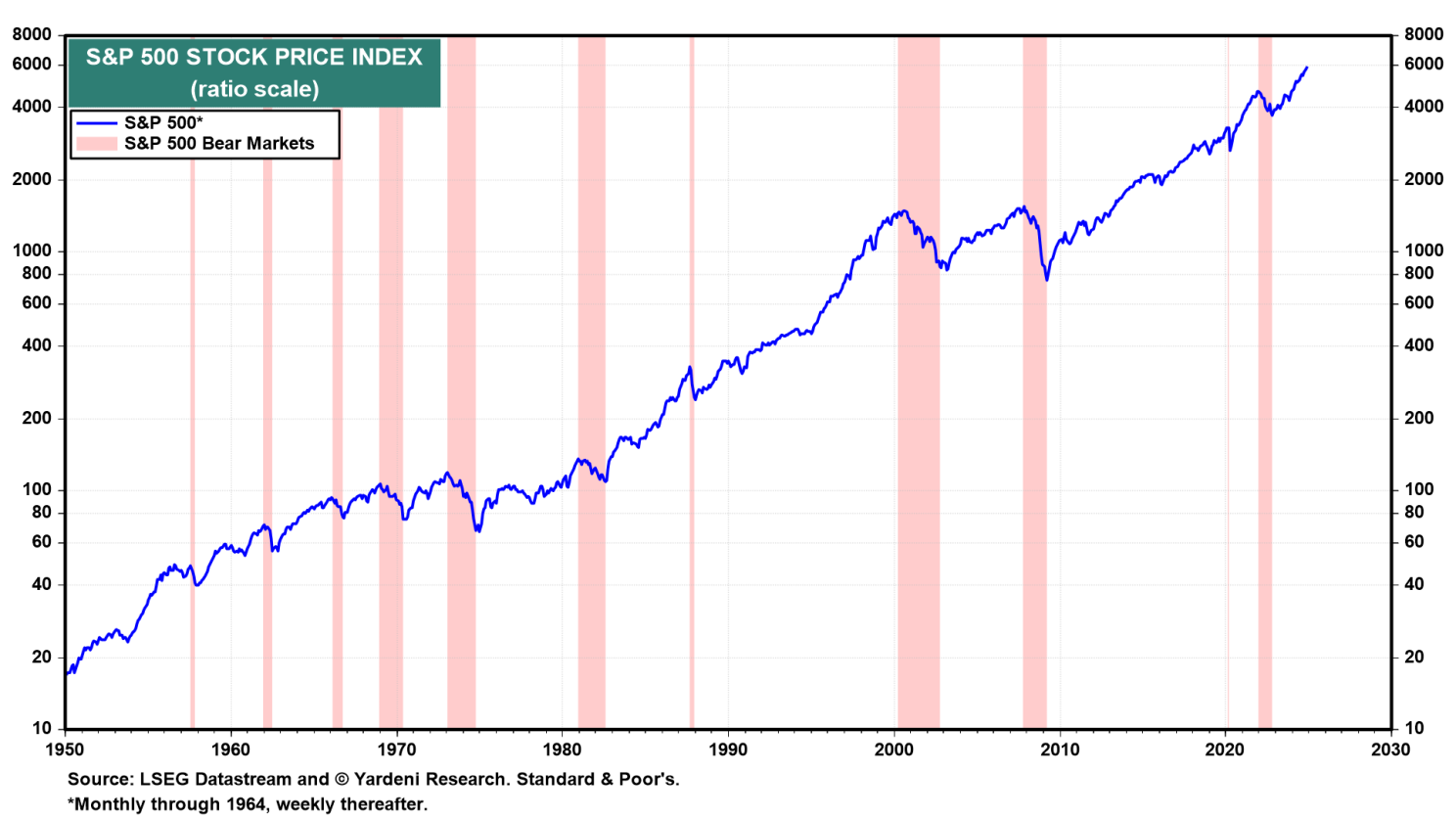

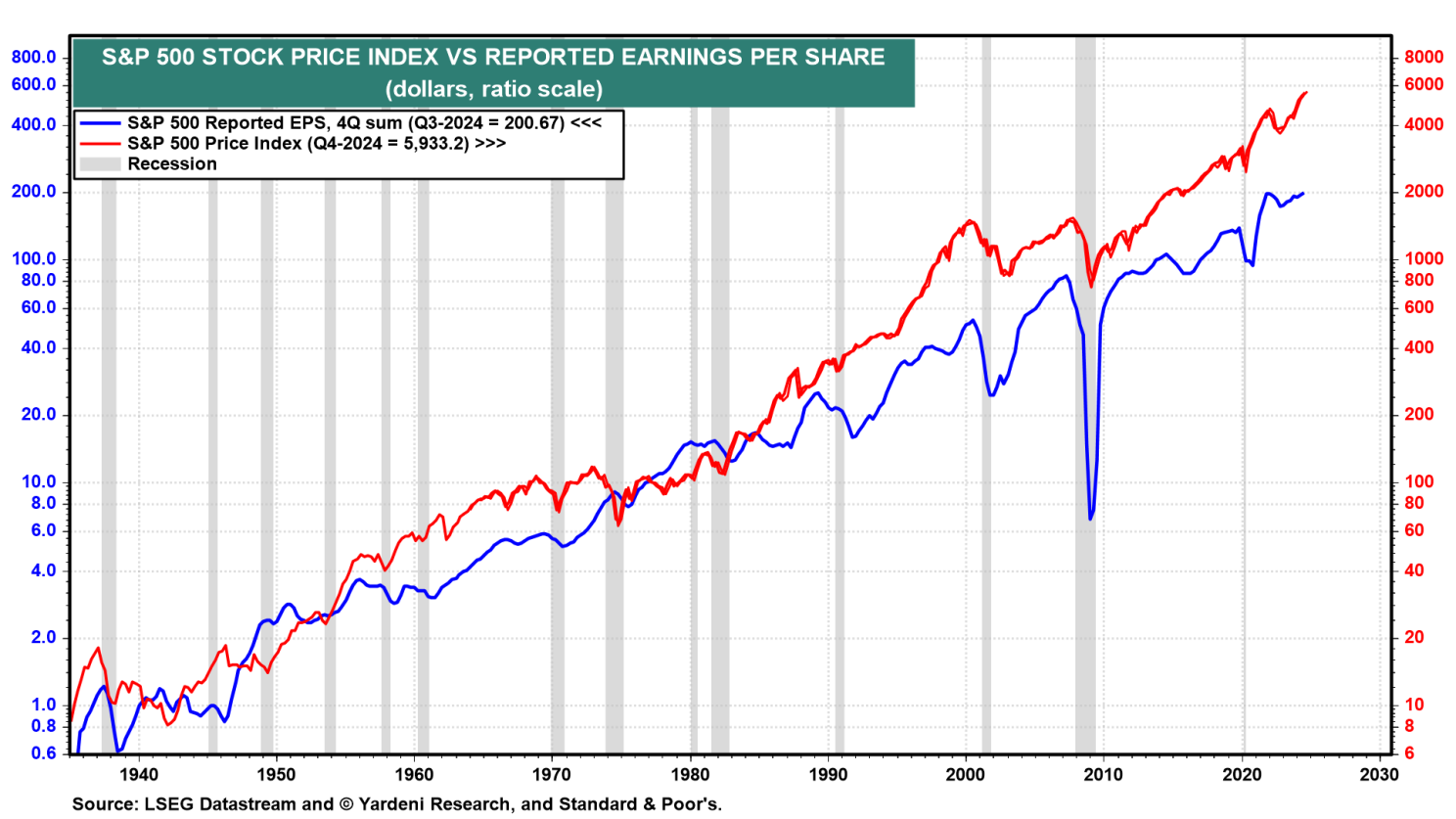

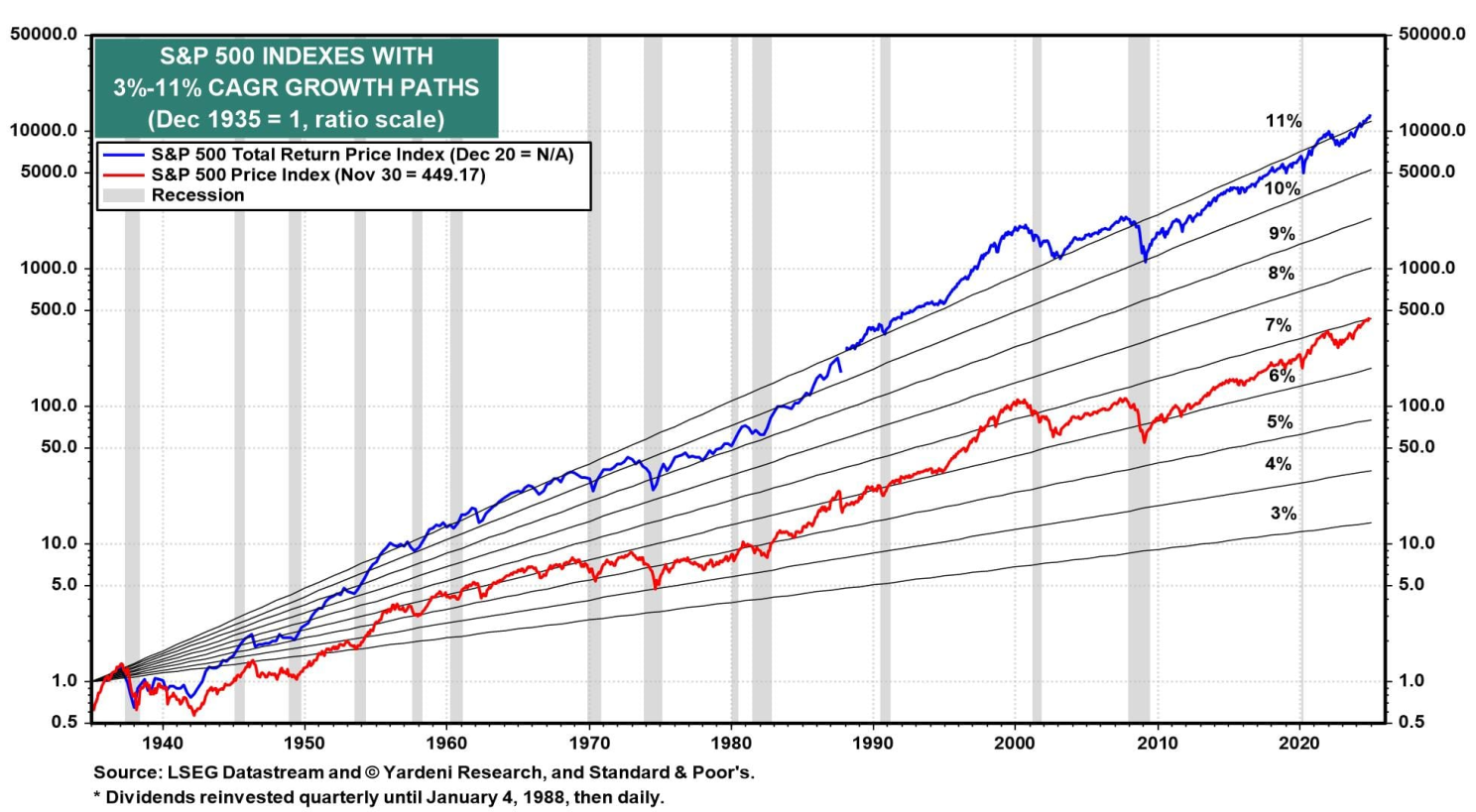

When I started my first job on Wall Street at EF Hutton in January 1978, the S&P 500 price index was at 90 (chart). Today, it is at 6000. That’s a 66.6-fold increase in 47 years. I wish I had been bullish over this entire period and had the funds to invest when I started my career. Over this entire period, there were just six bear markets, and they lasted on average only a bit more than one year.

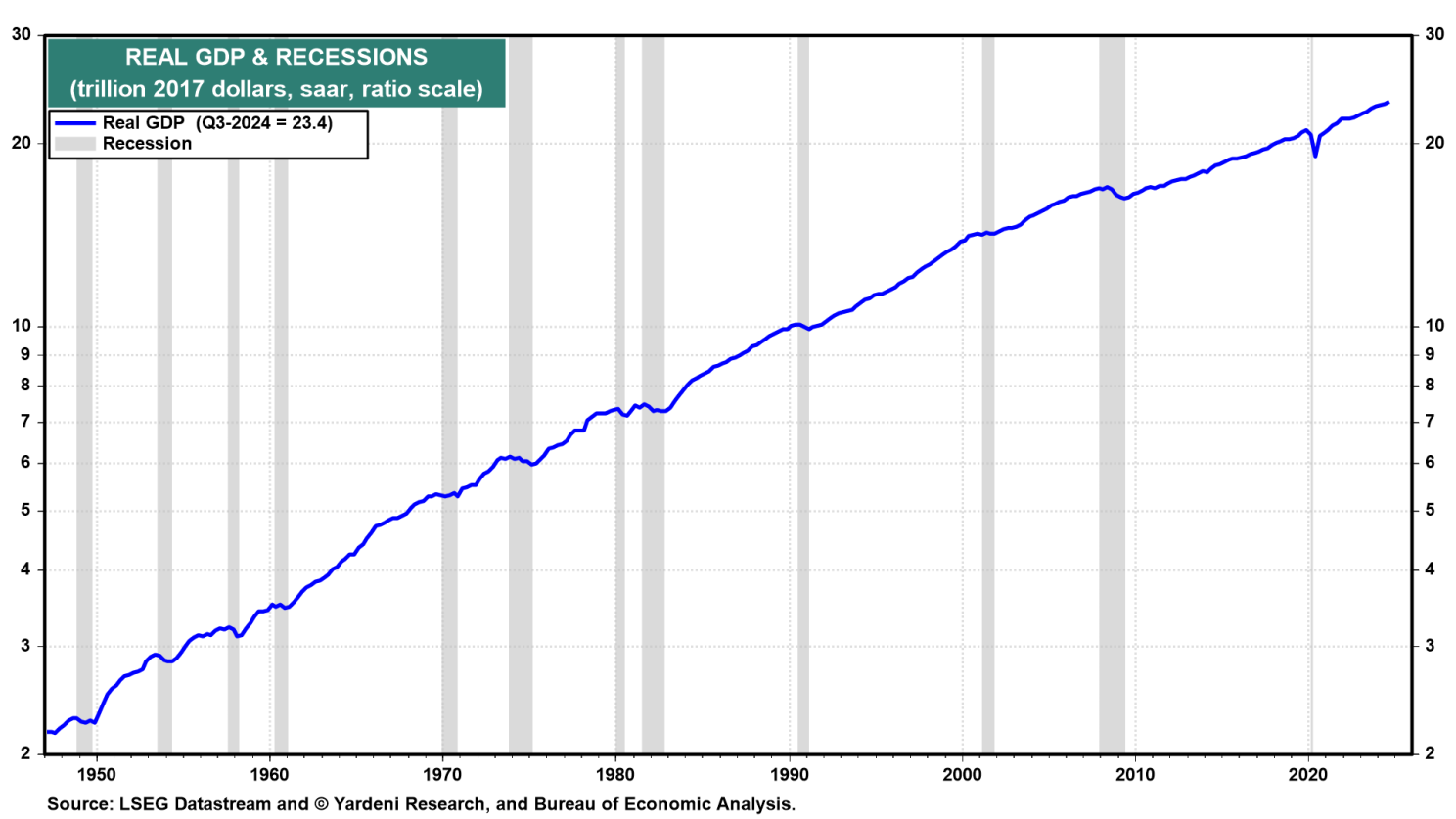

(2) Recessions are infrequent and don’t last long either

In the US, the National Bureau of Economic Research (NBER) is the authority that defines the starting and ending dates of recessions. According to the NBER, the average US recession over the period from 1854 to 2020 lasted about 17 months. In the post-World War II period, from 1945 to 2023, the average recession lasted about 10 months. Since 1945, there have been 12 recessions that occurred during just 13% of that time span (chart).

(3) One reason that bear markets are infrequent and don’t last very long is that they tend to be caused by recessions

Since the end of World War II, eight of the 10 bear markets have coincided with recessions.

(4) Bear-market have kept the secular bull market healthy for nearly a century

According to Seeking Alpha, there have been 28 bear markets in the S&P 500 since 1928, with an average decline of 35.6%. The average length of time was 289 days, or roughly 9.5 months. ABC News reported that since World War II, bear markets on average have taken 13 months to go from peak to trough and 27 months for the stock price index to recoup lost ground. The S&P 500 index has fallen an average of 33% during bear markets over that time frame.

Yet the stock market has been in a secular bull market since the Great Crash of the early 1930s.

Bear markets serve an important function for bull markets, helping to flush irrational exuberance out of valuations and allow price indexes to resume their climbs on a sounder footing.

My major complaint with Mr. Roberts’ criticism is that it rests on the unsubstantiated claim that my bullish forecasts usually had been bitten by reality. To be blunt, Mr. Roberts is uninformed about the accuracy of my forecasting track record, suggesting that the title of his article is clickbait. He also doesn’t seem to know that I always acknowledge and discuss the risks to my base-case forecast and assign subjective probabilities to it and one or two reasonable alternative scenarios.

Here is a brief overview of my forecasting track record, which often—but not always—has been optimistic and right:

(1) At the start of my career, I was bearish during the bear market in the early 1980s. I turned very bullish in August 1982, which was the bottom. I didn’t call the August top of the 1987 bear market, but I did call the bottom in December of that year.

I was one of the first disinflationists during the 1980s and predicted “hat-size” bond yields when the 10-year yield was well above 10%, which I surmised would be bullish for stocks. In the early 1990s, I argued that the end of the Cold War was bullish for stocks. That was a contrarian view at the time.

I was among the first strategists to identify the bullish consequences of the High-Tech Revolution during the early 1990s, and I recommended overweighting the Technology sector in the S&P 500.

(2) On May 9,1990, I first predicted Dow 5000 in 1993. It happened behind schedule in 1995. Then, I predicted “10,000 by 2000” for the Dow. It happened ahead of schedule on March 29, 1999.

(3) I turned bearish on the Tech sector and the stock market at the end of the 1990s. I did so for two reasons. Valuation multiples were too high, suggesting speculative excesses. I anticipated that the Y2K problem might cause a recession. I was right about that for the wrong reason. Everyone fixed the problem by upgrading their hardware and software. As a result, the demand for these was pulled forward and then dropped sharply, causing a recession at the beginning of 2000.

After China joined the World Trade Organization on December 11, 2001, I turned bullish on the global economic outlook and on Materials, Energy, and Industrials in the stock market. I turned bearish on Financials during June 2007. I wasn’t bearish enough because I didn’t expect the Fed to let Lehman fail. But in 2009, I called the stock market bottom on March 9 later that same month.

(4) During the subsequent bull market, which lasted until the pandemic hit in February 2020, I remained consistently bullish in the face of numerous selloffs. After the Great Financial Crisis in 2008, it was easy to alarm investors about another bear market. And the permabears did their best to do just that. I characterized the frequent sell-offs as panic attacks and compiled a list of them during that period, counting 66 all told during that bull market. I remained steadfastly bullish.

(5) I didn’t call the stock market’s peak on February 19, 2020. But I did call the bottom on March 23 a couple of days later. I expected a correction in early 2022. It turned into a relatively short bear market. The market bottomed on October 12, 2022. I identified that bottom later that month and stayed bullish. Now, I am expecting a short-lived correction in January 2025.

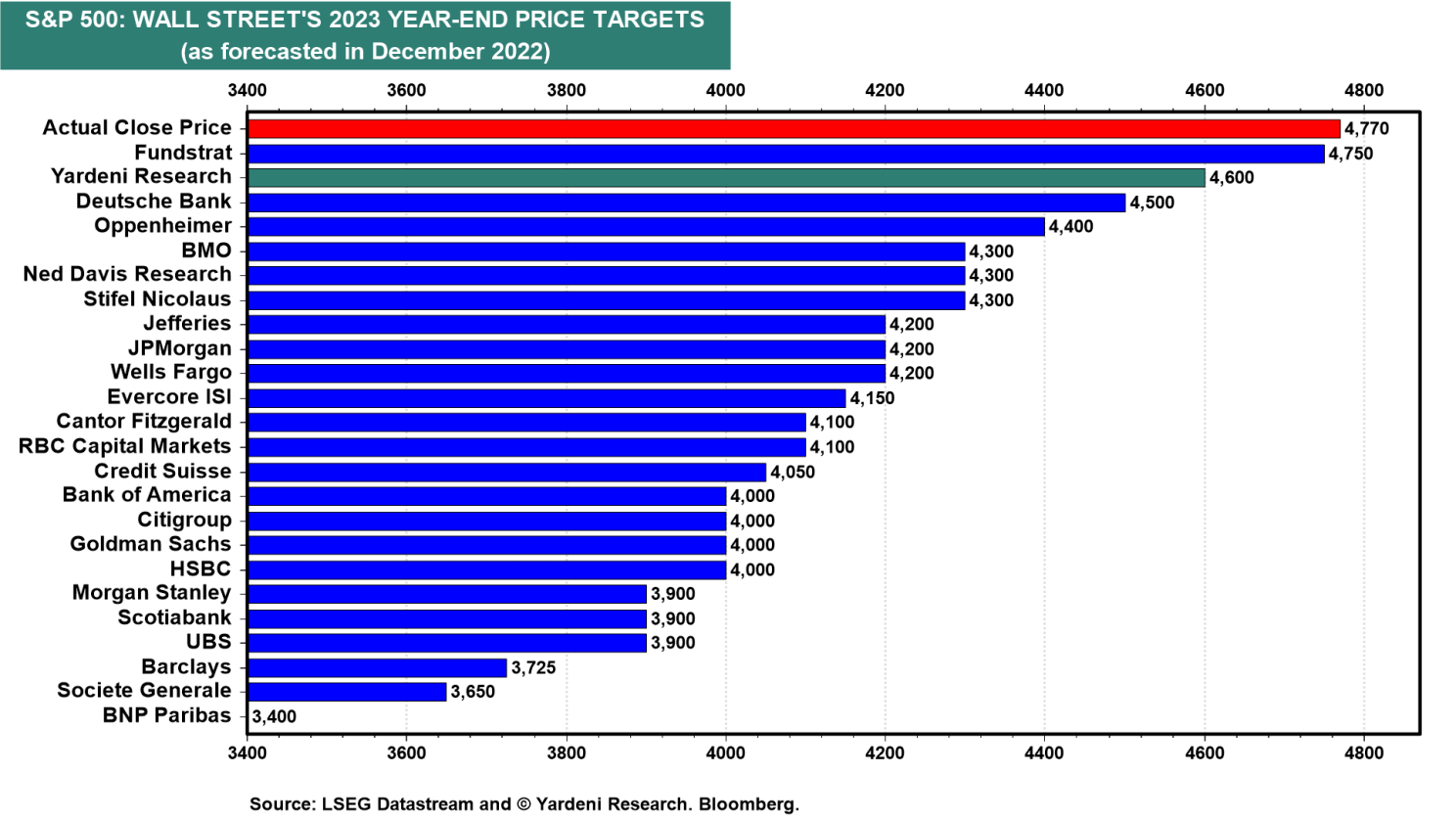

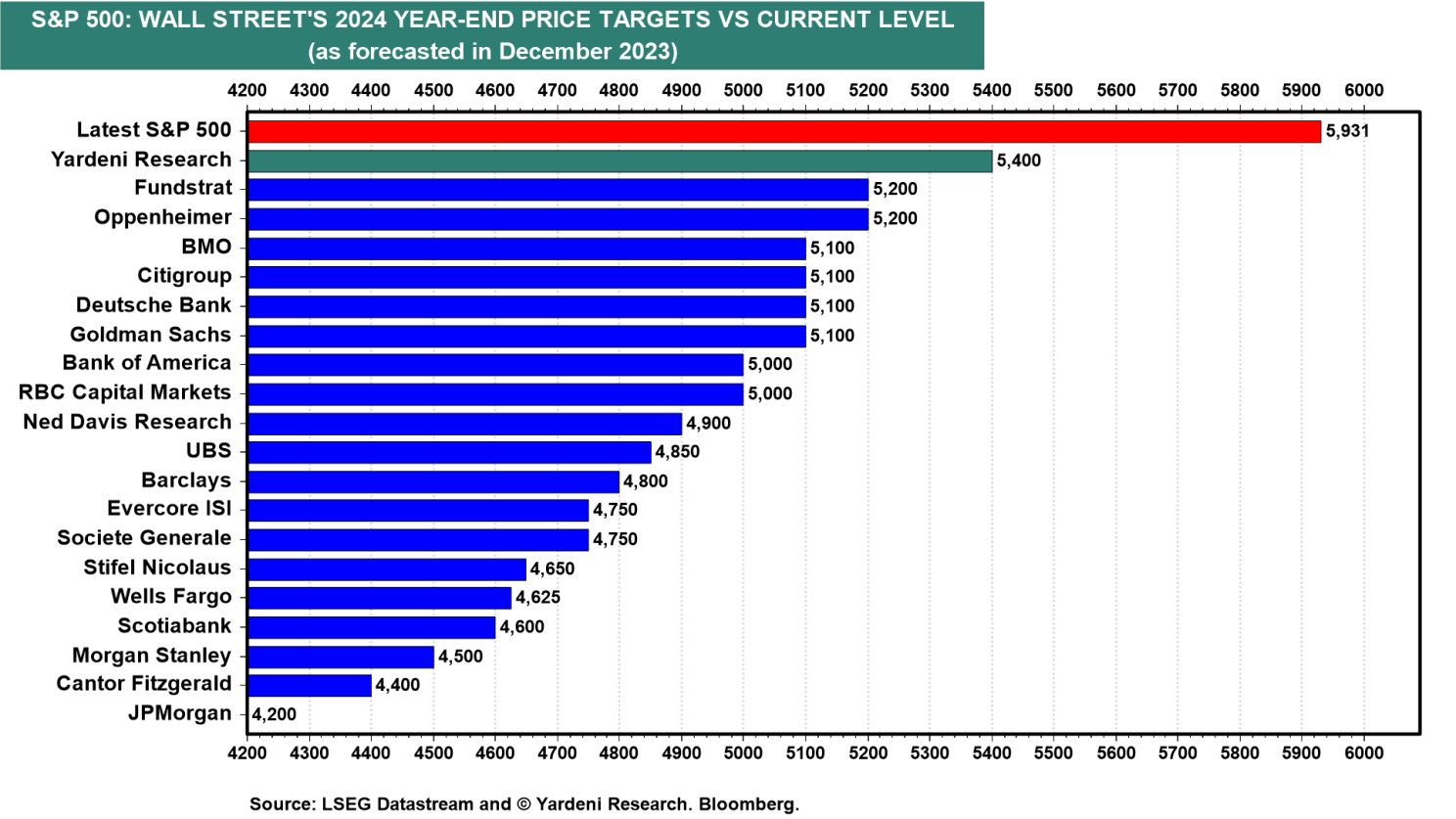

(6) At the start of 2023 and 2024, Fundstrat and Yardeni Research had the highest S&P 500 targets among Wall Street’s major research shops (charts).

(7) I was one of the only economists correctly to counter the widespread consensus view that the tightening of monetary policy by the Fed over the past three years would cause a recession. I explained that the economy was experiencing rolling recessions rather than an economy-wide downturn.

I countered the widespread notion that consumers would retrench once they depleted their $2 trillion of “excess saving,” by observing that retiring Baby Boomers were starting to spend the $75 trillion in their net worth. I argued that a credit crunch was unlikely, which also reduced the likelihood of a recession.

The Dark Side

In any event, no hard feelings: I like the permabears. A few of them are my friends. They are smart economists and strategists who tend to be bearish. I look to them for a thorough analysis of what could go wrong for the economy and the stock market. They are very vocal and fuel lots of pessimism about the future among the financial press and the public. According to Microsoft (NASDAQ:MSFT) CoPilot, this permabear crowd includes such luminaries as Jeremy Grantham, Marc Faber, Harry Dent, David Tice, Albert Edwards, John Hussman, Peter Schiff, Nouriel Roubini, and David Rosenberg.

The economists at Goldman Sachs (NYSE:GS) recently joined the dark side. They predict that the S&P 500 will produce annualized returns of only 3% (before accounting for inflation) over the next 10 years. According to the October 25 Briefings from Goldman Sachs (which is publicly available): “The most important variable in this forecast is starting valuation. ‘In theory, a high starting price, all else equal, implies a lower forward return,’ writes David Kostin, chief US equity strategist at Goldman Sachs Research.”

That suggests that starting valuations now are high relative to what they’ll be in the future—so it seems to assume that they’ll be lower 10 years from now. However, that’s clearly a “known unknown”: We know that 10 years from now, valuations will be higher, the same, or lower than now; but we don’t know which.

Granted, historical standards stretch current valuation multiples; but in 10 years, they might still be as high as they are now even with drops along the way. If so, then over the next 10 years the S&P 500 price index would rise along with its earnings—at a pace that should be at least twice as fast as Goldman’s 3% annual projection and closer to 11% including reinvested dividends (charts). In our Roaring 2020s scenario (and maybe Roaring 2030s), valuations might be higher than they are today.

The Force

So let the Force be with you. However, you must choose whether to join the dark side or the light side of the Force. The permabears have chosen the dark side. A few are famous because they called a market top once. They’ve never called market bottoms with only one exception. A long time ago in a galaxy far, far away when I was just starting my career, Henry Kaufman, the chief economist of Salomon Brothers, also called the stock market bottom in August 1982 after having been correctly very bearish on bonds for several years.

So the permabears tend to get you out of the stock market often well before a significant top. When the market falls, they tend to turn more bearish. Even if they get you out at the top, they likely won’t get you back in at the bottom. In contrast, permabulls like myself tend to agree with this old adage: “Time in the market beats timing the market.” According to CoPilot, our crowd includes Warren Buffett, Jeremy Siegel, Tom Lee, Jim Paulsen, and Brian Belski. Here’s another old Wall Street adage: “Bears sound smart, but bulls make you money.”

For those interested in a more comprehensive review of my forecasts and how I formulated them, my 2018 book titled Predicting the Markets: A Professional Autobiography might be of interest. If you are my age, you should find it a walk down Memory Lane. For younger students of the market, it’s a good way to catch up on the past 40-plus years.