The past 12 months have seen more Aussies struggle to put food on the table, with 3.7 million households experiencing moderate to severe food insecurity, according to Foodbank Australia’s 2023 Hunger Report.

- 36% of Australian households are experiencing food insecurity, Foodbank Australia has found

- More than 2.3 million households are being forced to skip meals or forego food for days

- The cost-of-living crisis is exacerbating food insecurity, Foodbank Australia CEO Brianna Casey said

- Australians are turning to BNPL services to pay for food and other essentials

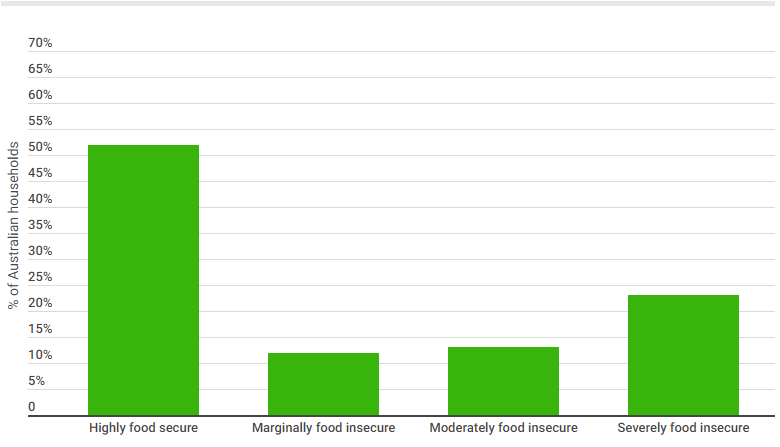

The report surveyed 4,342 Australian adults in July, finding just 52% of households are highly food secure – 3 percentage points fewer than in 2022.

Food insecurity can vary in severity.

Those marginally affected worry about losing access to food while others who are moderately impacted are forced to reduce the quality or variety of food they buy.

Nearly a quarter of households are facing severe food insecurity and have been forced to skip meals or forego food for entire days, the non-profit organisation found.

Food insecurity among households

“It’s clear the cost-of-living crisis is exacerbating the challenges facing those in vulnerable circumstances, and forcing people to make compromises on what, and when they are eating,” Foodbank Australia CEO Brianna Casey said.

Nearly half – 48% – are now anxious about or struggling with the accessibility of their food.

That’s up from 45% in 2022 and, if the trend continues, more than half of the nation could be struggling to put food on the table by the end of this year.

Many households currently experiencing food insecurity are doing so for the first time and are reluctant to reach out for help, Foodbank noted.

“Food insecurity is waking early and sending your child off to school with a rumbling tummy and empty lunchbox because you’ve been forced into an impossible choice between paying the rent or buying food that week,” Ms Casey said.

“[It's] living at home alone as a pensioner, convincing yourself that three meals a day is a luxury [or] rushing to the fruit platter at a working lunch in the office because fresh fruit and vegetables have become a treat, rather than a dietary staple.

“Food insecurity is now having a mortgage, a full-time job and a side hustle, yet food is a discretionary spend in the household budget.

“I wish these were hypothetical examples.”

Around eight in 10 people facing food insecurity in 2023 blame the rising cost of living for their struggles, while four in 10 point the finger at low or falling incomes and government benefits.

Changes in households or living arrangements are impacting 26% of those who are food insecure and limited ability to travel to get food is hampering 16%.

The price of food rose 7.5% over the 12 months to June, the Australian Bureau of Statistics’ (ABS) latest quarterly consumer price index (CPI) read found.

That makes the category one of the biggest drivers of annual inflation, along with the cost of housing (up 8.1% year-on-year).

Aussies resort to BNPL for food and essentials

The vast majority of those living in food insecurity have adjusted their grocery shopping habits, with fresh produce and proteins scratched from 48% of lists.

Nearly two thirds, meanwhile, have changed their housing and finances, dipping into housing savings or spending more on credit cards or buy now pay later (BNPL) services.

Increased essential spending on BNPL has been noticed by consumer protection bodies, many of whom have today put out a warning on Afterpay’s recently released subscription model.

The model, dubbed Afterpay Plus, costs $9.99 a month and is accepted anywhere that takes Apple (NASDAQ:AAPL) Pay, Google (NASDAQ:GOOGL) Pay, or Samsung (KS:005930) Pay.

Many, including Financial Counselling Australia and the Financial Rights Legal Centre, believe the product essentially allows consumers access to a loan with little to no affordability checks.

“I am really concerned, as our financial counsellors on the National Debt Helpline often hear from people using BNPL for daily essentials like food, energy, and telco services,” Consumer Action Law Centre CEO Stephanie Tonkin said.

“People are doing it tough right now and are extremely vulnerable to unregulated credit,” Consumer Credit Legal Service principal solicitor Roberta Grealish said.

“People who are resorting to BNPL for essentials like food are obviously struggling to put a meal on the table – they do not need additional fees added to the mix – it’s a recipe for a debt disaster.”

The Australian Financial Complaints Authority (AFCA) fielded 57% more complaints against BNPL services in 2022-2023 than it did the prior year.

AFCA chief ombudsman and CEO David Locke said the increase underlines the importance of the Federal Government’s intent to regulate BNPL services under the Credit Act, as announced in May.

“The BNPL industry desperately needs proper safe lending laws for their products, or they will continue to cause harm,” Ms Tonkin said.

"1 in 3 Aussie households struggle to put food on the table" was originally published on Savings.com.au and was republished with permission.