The critical minerals boom is taking off – all the signs are there.

Metals prices are climbing, exploration permit applications are skyrocketing and investment companies are hunting for a great deal on any new battery or critical mineral projects they can get their hands on.

Lithium, rare earth elements, nickel, copper, alumina – all of these minerals and more are absolutely vital to decarbonisation and the energy economy’s transformation, and right now the world just can’t get enough of them.

That begs the question – what are critical minerals? Why are they so critical? Are we in danger of digging too much of them out of the ground? What kind of opportunity do they represent?

Proactive asked two critical mineral experts questions surrounding the battery metals boom and whether we’re in danger of mining too much – or too little.

In this article:

- What are critical minerals?

- Are we on track to mine too many?

- What opportunities does a critical mineral boom offer?

- Mining for the future

What are critical minerals?

Dr Chris Vernon is a senior principal research scientist with the CSIRO, who leads the Green Mineral Technologies initiative – he’s also the resident critical minerals expert.

“Critical minerals are interesting,” Vernon began.

“If you go back to World War I, or even just before, the US had a critical resource list that included things like whale oil, iron and bronze.

“A US geologist once said to me, ‘Critical minerals are minerals you want and can’t get’, I think that’s the simplest explanation.”

In other words, they’re minerals vital to the smooth running and continued security of a nation’s economy that are threatened by potential supply chain disruptions – be they economic, political or environmental in nature.

Carl Spandler, Associate Professor of the University of Adelaide’s Critical Minerals Research Centre, explained that long lead times on mining projects contribute to the problem.

“Supply risk means economic risk. Are we going to need these particular metals in five years’ time, or 10 years’ time? Those are the sort of timeframes that companies would be looking to invest in and set up these projects – they take time,” Spandler clarified.

The entwined association with supply and demand factors also means every country has its own critical mineral list to cater to individual resource, manufacturing and supply requirements.

“At the moment, the critical mineral list in Australia has at least 26 minerals on it,” Vernon described.

That’s not even counting individual elements – rare earth elements number either 15 or 17 individual minerals, depending on how you count them, and there are six platinum group elements, meaning Australia’s expanded critical mineral list covers about half the naturally occurring elements on earth.

“The importance of critical minerals at the moment is that a lot of them are required for the coming energy transformation – some say transition, but I think it’s going to be a little more urgent than that,” Vernon continued.

“These are the elements that go into solar panels, or a storage battery, or an EV motor, or a wind turbine, or rectifiers to turn DC currents into AC, etc. So, a really wide range of elements.”

Are we on track to mine too many critical minerals?

Analysts, miners, manufacturers and governments all seem to agree: We’re staring a massive supply shortfall in the face for a whole basketful of critical minerals; lithium, cobalt, nickel, copper and graphite are chief among them.

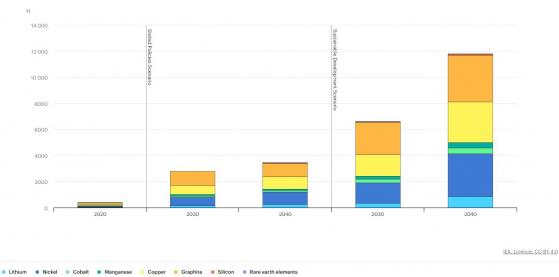

Demand is growing at exponential rates, as the graph below from the International Energy Agency demonstrates.

Total mineral demand for clean energy technologies by scenario, 2020-2040:

Left: 2020 demand, Centre: current policy requirements, Right: sustainable development scenario. Source: IEA, Total mineral demand from new EV sales by scenario, 2020-2040, IEA, Paris.

While many companies are already moving to fill that gap, as previously touched on, it takes an average of 16.5 years to take a mining project from discovery to production.

“Even if we discovered ore deposits today, they're not going to come online, necessarily, till as long as 2040,” Spandler said.

“We're running out of time, rapidly.”

Discovery and exploration in light blue, construction planning in navy blue and construction to production in green. Source: IEA, Global average lead times from discovery to production, 2010-2019, IEA, Paris

So, are we heading for a massive critical minerals shortfall?

“It really depends what mineral or material you look at,” Vernon emphasised. “Lithium, for example … I laughed a few years ago when somebody was predicting an almost overnight dearth of supply.

“At the time, I looked around Western Australia and went ‘Well, hang on, we could supply the entire world’s demand from our mothballed capacity’.

“That will change of course, as demand ramps up, but I’m reasonably confident we’ll be able to meet demand with things like lithium. Chile, Argentina, Bolivia, China, they’ve got a lot of lithium.”

As for the other minerals critical to decarbonisation, Vernon isn’t so sure.

“I think it’s more the sleeper minerals we need to worry about – things like cobalt, maybe not nickel, but we don’t have a lot of battery-grade nickel either,” Vernon admitted.

“Copper is definitely a sleeper for me because electrification means more wires, everything needs copper.

“If you look around the world, the known copper deposits are pretty low-grade at the moment, and it doesn’t grow on trees.

“Rare earths is another interesting one because most of the supply comes out of China – we do have a lot of really good prospective rare earth mines here in Australia, but how many of those are actually producing and getting to market at the moment?

“Very few.”

While all the data points to a huge supply dearth, surely rising mineral prices will encourage more and more companies to invest in and advance mines, and battery chemistries are also being constantly refined, reducing the need for scarce resources.

Could that lead to an oversaturation within the next few years, rather than the supply void currently being predicted?

“I think there is more danger of failing to meet demand than producing too much because we’re seeing a really aggressive move to decarbonise in a lot of countries,” Vernon disagreed.

“If you’re talking small marginal increases in renewables, that’s not a problem, but if you want to suddenly roll out a few gigawatts, and there are 90 other countries that want to roll out another 100 gigawatts, everybody’s after the same thing at the same time.

“For example, someone told me recently that you if put in an order for a large wind turbine at the moment, you’re guaranteed delivery by 2027.

“That doesn’t seem like a really rapid rollout to me.

“There’s a danger that if we don’t mine enough, there just won’t be enough material to produce these things and we’re on a pretty aggressive course to decarbonise.”

What opportunities does a critical mineral boom offer?

Australia is a country blessed by circumstance.

We have abundant mineral resources of almost all the critical minerals, the will and expertise to leverage them, and endless amounts of wind and sun.

In 2021, we became the number one producer of lithium and we sit in the top five for cobalt, manganese, antimony and rare earth minerals.

We also hold the largest recoverable resources of tantalum, zircon, rutile (naturally occurring titanium) and nickel, and rank in the top five for lithium, cobalt, tungsten, vanadium, niobium, antimony and manganese, according to Geoscience Australia.

“The critical minerals boom is a massive opportunity. But, depending on which ones you’re talking about, the window – while open now – is going to close pretty quickly,” Vernon said.

“We’ve got a fantastic opportunity, but I don’t think it’s the traditional opportunity.

“Traditionally, we’ve been very good at digging things up, making concentrates, sticking them on a ship, or refining it just enough to be attractive to someone to buy.

“I think the opportunity at the moment is to go a little further in the processing, to aggressively take hold of some of those markets, for example in the US and Europe, Japan, India, South Korea, with a slightly more refined product or even a first level manufacturing material to take advantage of the very rapid uptake in those economies.”

That would require more downstream processing and manufacturing, something Australia has historically left to nations with lower labour costs.

There are other ways to save on costs, however, says Spandler.

“Part of the reason these materials are considered critical is because of where they’re manufactured, as well as sourced,” he said.

“We should be doing that in Australia. We have an advantage in that we have huge potential for renewable energy.

“Energy costs are one of the biggest additional costs to manufacturing. We can potentially manufacture these products much more cheaply once we get those renewable energy systems up and running.

“So, I think there is a really good case to be made for manufacturing batteries, for manufacturing magnets that we need for electric motors and for wind turbines, etc.

“We have the raw materials here. We could do it ourselves.”

Mining for the future

Australia appears set on a golden path – endowed with plenty of renewable energy, critical minerals and manufacturing know-how, we have an opportunity to become one of the largest producers of green critical minerals in the world.

But what then? Once we’ve got our wind turbines and our electric vehicles and our big grid batteries feeding stored energy back into the system – what will mining look like, once the energy transition is complete and we’ve dug up the critical minerals that we need?

“I think it’s inevitable that we will build a circular economy,” Vernon stated, “Mining may inevitably start to trail off from there. It’s probably not going to happen in my lifetime, but it will happen.

“I think mining companies need to gear up and think about what’s next.”

The European Parliament defines a circular economy as “a model of production and consumption, which involves sharing, leasing, reusing, repairing, refurbishing and recycling existing materials and products as long as possible”.

The idea is to reduce waste to an absolute minimum. When a product reaches the end of its life, the materials are refurbished, reused and recycled to be used again and again, thereby creating further value.

“Make no mistake, recycling will be required,” Vernon insisted, “Do we want to become the country that takes the electric vehicles from our shores and ships them somewhere else for recycling? Please, we don’t want that.

“I also think there’s a social responsibility aspect that a lot of these companies are recognising now – If we’re producing the stuff, we don’t want it in landfill in 20 years, we want to be a company that brings it back and gives it another life.”

According to the CSIRO, only 10% of Australia’s lithium-ion battery waste was recycled in 2021, with the rest either ending up in mixed landfill domestically, posing significant fire and explosion risk, or being shipped abroad under strict export conditions for further processing.

Developing and expanding recycling capabilities for critical minerals, and specifically batteries – as companies like Lithium Australia and Neometals are doing – would be the last step in extracting maximum value from the net-zero supply chain and securing a future free of the threat of environmental collapse.

Only time will tell how much of this critical opportunity Australia can grasp.

Read more on Proactive Investors AU