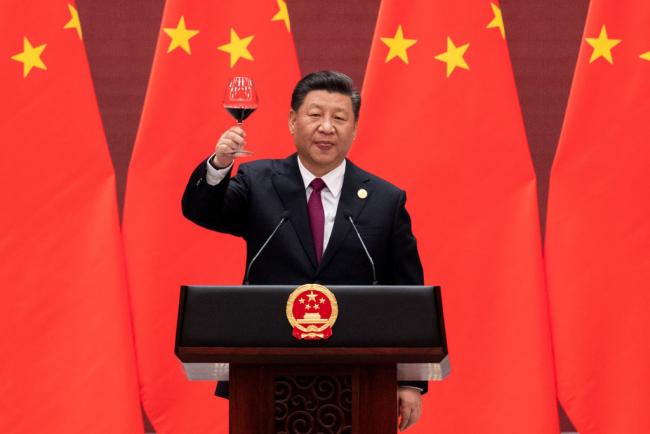

(Bloomberg Opinion) -- China’s second Belt and Road Forum, convened by President Xi Jinping in Beijing last week, looked less like an imperial celebration than a summit meeting. Xi’s tone had also become less triumphant. Instead, he spoke about a commitment to zero corruption. He promised to make the environment a central concern for any infrastructure projects included in his globe-spanning Belt and Road Initiative. He even adopted a term used by archrival Japan to denigrate Chinese projects, vowing that Chinese companies would build only “quality” infrastructure.

That last rhetorical change is indicative. Japan has long been the biggest builder — and funder — of infrastructure in emerging Asia. Faced with Chinese competition, the Japanese refused to participate in the Belt and Road, while insisting that their “quality” projects were of a different class than China’s. This slighting comparison seems to have penetrated. First the Chinese leadership declared an armistice with the Japanese on infrastructure last September. Now, at least rhetorically, they’re acknowledging doubts about the viability and motivations of Chinese projects.

A chastened Beijing is a gratifying thing to see, given that it has spent the last few years pushing the Belt and Road in every possible forum and every bilateral relationship, with very little concern for how the initiative would be perceived in host countries or how their politics would be disrupted. Still, it would be very unwise to assume, first, that Xi’s rhetorical shift will lead to genuine changes in procedure, policy or even principle; and second, therefore, that the Belt and Road is now a safe partner and destination for foreign capital.

Many assume that Beijing has moderated its approach in response to the headwinds that its initiative has encountered across Asia, where project after project has run into financial and political trouble. But that’s not the real story — or, at any rate, not the whole story. It matters just as much that the People’s Republic isn’t quite as rich as everyone likes to think.

While Beijing has deep pockets, certainly, they aren’t deep enough to finance the trillions of dollars of infrastructure that Chinese leaders have promised at one time or another. The numbers so far haven’t been encouraging; at the Forum, it was announced that Chinese companies had invested $90 billion in Belt and Road countries, which sounds like a lot but is only a drop in the bucket. Moreover, we can’t be sure how much of that investment eventually had to be supplemented by equivalent amounts of domestic financing in each country.

The Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank and the BRICS — or “New Development” — Bank have $150 billion on hand and the Silk Road Infrastructure Fund has $40 billion. Chinese companies can access, according to Gavekal Research, just under $600 billion from the state-controlled financial sector.

If they soak up all that excess capital, though, development plans within China might run short. It’s safe to assume the latter will be assigned a higher priority by Beijing.

Thus, the fact that Beijing wants to reboot the Belt and Road and bring in foreign partners doesn’t necessarily reflect a change of heart. The real issue seems to be that China’s ambitions overshot its purse. What Chinese leaders want, above all, is for global private capital, including from the West, to help sustain the initiative.

Certainly, more private finance, especially institutional finance, should be flowing into infrastructure in the global South. That said, the Belt and Road is the wrong destination for Western capital. While there may be some opportunities for profit-making, the initiative as a whole is set up to benefit Chinese companies. Worse, engaging with China means that banks and institutional investors will be signing up to a project that has multiple and varied objectives, not all of them economically rational. That is a deeply risky thing to do — and far from the most sensible way for private finance to fund infrastructure.

It’s not the private sector’s responsibility to fix the Belt and Road or to get it to work. That’s China’s job, and Beijing should be busy scaling down projects to a size that’s affordable.

It isn’t surprising that some in the West might find Xi’s appeal attractive. That’s because neither Western governments nor multilateral agencies such as the World Bank have worked hard enough to get private finance involved in building infrastructure in the developing world. That needs to change, in part by relaxing regulations that induce large pools of capital to keep their money unproductive at home, and in part by forcing development agencies such as the World Bank to work more closely with Western finance.

Beijing has realized it cannot finance its attempt at hegemony with its own cash. It would be ironic if it ends up doing so with Western money, simply because the West is too lazy to create its own pipelines for investment in infrastructure.