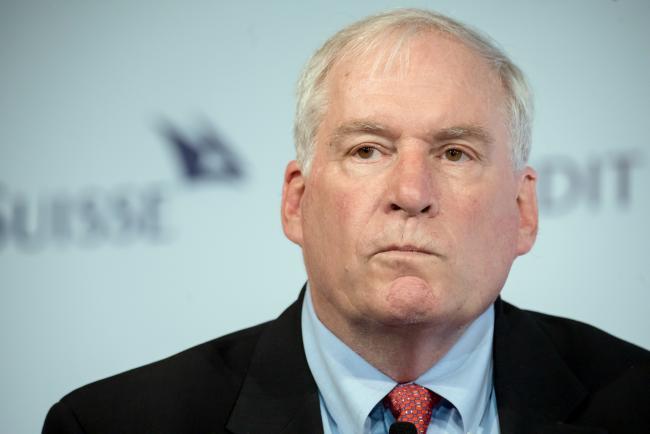

(Bloomberg) -- Federal Reserve Bank of Boston President Eric Rosengren still thinks the central bank’s next move for interest rates is more likely to be a hike than a cut. He just won’t be surprised if that turns out wrong.

In a March 22 interview Rosengren said he’s “more optimistic” over the outlook for economic growth and inflation than most of his colleagues on the central bank’s policy-setting Federal Open Market Committee. If that turns out to be right, he said, “it is possible the next move would be up.”

“I’m also quite willing to accept that if the economy weakens and the global economy weakens more than I’m anticipating -- and the recent data could be consistent with that, then the next move could be down,” he said.

Rosengren is a voting member this year of the FOMC. At their March 19-20 meeting, Fed officials marked down their forecasts, sending their median projection for rate increases in 2019 to zero from two. Chairman Jerome Powell also set an even-handed tone regarding future moves, telling reporters after the gathering the economy isn’t pushing the Fed toward either a cut or an increase in rates.

Rosengren’s outlook would appear to place him among the six officials projecting at least one increase this year. The majority of policy makers said no move is likely.

Rosengren, however, said Fed watchers should spend less time eyeing rate projections and instead ask how convinced officials are the economy can avoid a more serious slowdown. Over the past six months policy makers have dropped their median forecast for growth this year to 2.1 percent from 2.5 percent.

That weaker outlook is further threatened, he said, chiefly by international risks.

“Both China and Europe have been weak, and there’s a reason to be concerned they can be weaker than we’re currently projecting,” he said. “That, by itself, would be a good reason to pause” rate increases, he added, as the Fed did in January after hiking four times in 2018.

The second big risk factor in Rosengren’s eyes is the central bank’s admittedly poor record of hitting its inflation target in any sustained way over many years.

The Fed describes its 2 percent objective as “symmetric,” meaning it is no more concerned about overshooting than undershooting. Yet the Fed’s preferred gauge of price pressures, after stripping out volatile fuel and food components, has reached the target in just five of of the months since it was established in January 2012.

Low Risk

“The distribution of inflation outcomes doesn’t look like a symmetric distribution right now,” Rosengren said. “We’ve not been taking enough risk to allow the economy to clearly embed a 2 percent inflation rate.”

That raises the worry, he added, that the public will think of the target as a ceiling. Still, he pushed back against the notion that the Fed and central banks in other developed economies have lost the ability to generate sufficient inflation. Low unemployment will eventually lead to higher prices, he said. It will simply take much longer than economists had previously expected.

“I think we are running a relatively high-pressure economy, so I do expect that will be sufficient, that we will get to our 2 percent target,’ he said. “I don’t think the basic mechanics of wages and price-setting have completely changed.”

Rosengren acknowledged that bond investors sent policy makers a negative signal last week when the yield on 10-year Treasuries fell below 3-month rates for the first time since 2007. Such yield-curve inversions have frequently preceded recessions. Investors now see better than a 50 percent chance of a Fed rate cut by September, according to pricing in federal funds futures contracts.

“I don’t think it’s determinative of what we should do, but we should certainly try to square markets with what we think the most likely outcome is, and try to understand why they are similar or different,” he said.