It’s important, I think, that I occasionally remind readers of a fact that is supported by overwhelming quantitative evidence, and yet virtually ignored by a wide majority of economists (and central bankers): inflation is a consequence of the stock of money growing faster than real economic growth. Period.

MV=PQ

That doesn’t mean that forecasting inflation is easy if we remember that fact, but at least we can make good directional predictions when, say, the stock of money rises 25% in a year, instead of mouthing some nonsense about inflation in such a case being “transitory.”

However, I realize that when someone mentions that equation a lot of people tune out, thinking this has become a religious argument between monetarists and Keynesians. So let me toss out some data. Keep in mind, that there is measurement error in statistics for the money supply, real GDP (especially), and prices. And, as I’ve written before, sharp changes in M can cause a short-term impact on velocity until Q and P can catch up – my ‘trailer attached by a spring’ analogy. But over time, a shock move in velocity becomes less important (and reverses, which is what we are in the middle of), and so we would expect by simple algebra to see that a good prediction of the change in the price level is given by M/Q. Is it?

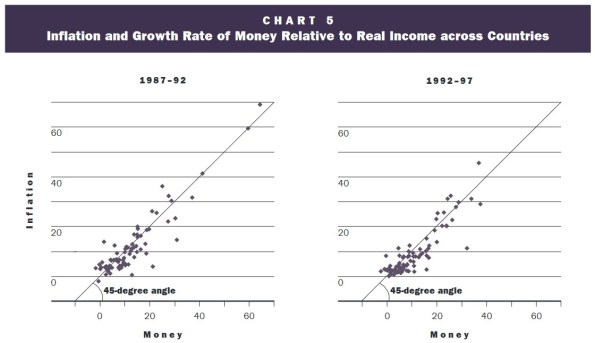

First, let me share one of my favorite charts from a Federal Reserve Economic Review. I’ve been using this for years.

This is over 5-year periods, and you can see that there’s a pretty good correlation – especially for large changes – in the change in the ratio of money/income and the change in prices. (By the way, the original article is still worth reading).

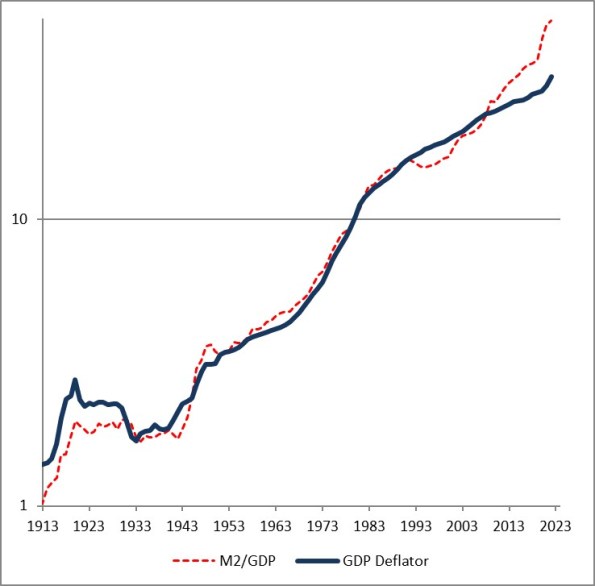

Here is another chart from that note, updated by me through the end of 2022.

The fact that the price level has gone up a little bit less than the ratio of money to GDP over time is a reflection of the fact that money velocity has gone down slightly, and then more quickly, over the last 110 years. If you think velocity will fully revert, then the blue line will eventually converge with the red line – but in my mind, there’s no reason to believe that velocity is stable or entirely mean-reverting over time, only that it doesn’t permanently trend higher or lower like money, prices, and GDP do.

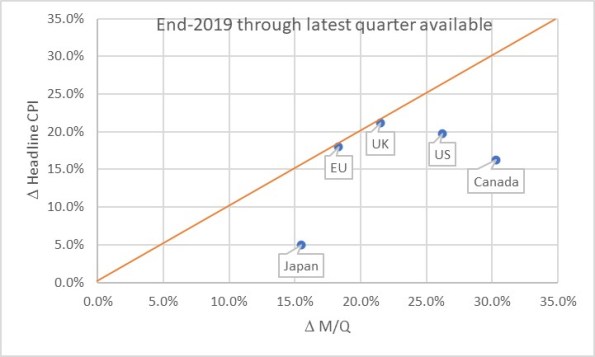

Obviously, this leads us to the question of where we are now. Here is a chart of the change in headline prices (CPI) as a function of the change in M/Q for five countries/regions.

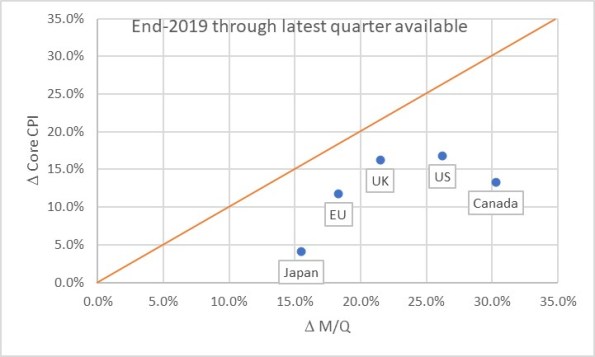

The chart basically says that the UK and EU have seen prices move almost exactly what you would have predicted if you had known in advance what M and Q were going to do. Naturally, none of us knew that. Japan, the US, and Canada haven’t seen prices rise as much as you would have expected, yet. One of the reasons why not is the effect I mentioned earlier: the dump of money into accounts during COVID was so fast that there was no time for prices to adjust. Actually, it’s only this close because food and energy adjust more rapidly…if you look at the picture with just core inflation, it appears there’s still some lifting to do to get back to the 45-degree line. As energy prices and food prices mean some, core inflation should stay a little bubbly for a while.

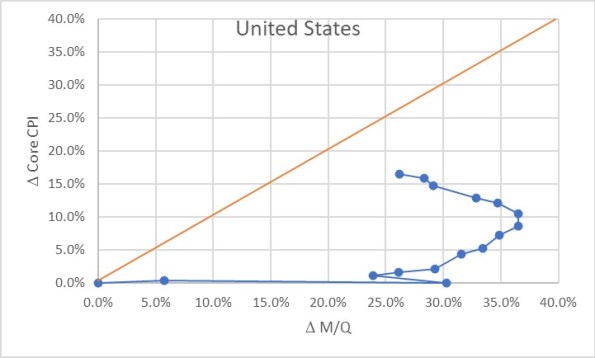

Now, there are three ways to get back to the line. We can see prices rise. We can see GDP rise. Or we can see the money supply fall. The latter two effects are better for consumers. The “GDP rises” is the best for everyone, although that’s the slowest-moving of the pieces. The “money supply fall” option is the best for consumers, but the worst for investors. Presently, we’re seeing a little bit of all three. But here is where I should take a moment to highlight how important the Fed’s balance sheet reduction has been in this process. Here is a chart from 2019Q4 to the present, just for the US, showing how this relationship developed over time.

Initially, of course, there was a massive increase in money with no change in prices, as COVID hit in 2020. The point at (30%, 0%) is what the Fed had to work with as the lockdowns began to be lifted in late summer 2020. The sharp single-quarter reversal there was the result of the massive GDP spike in 2020Q3.

At that point, we would have anticipated that if nothing else happened, we would see a gradual 23% or so increase in the price level. If the Fed had immediately pulled back on the money printing, probably a lot less. Instead, the money printing continued for quite a while until by the middle of 2022 we were looking at a change in M/Q of about 37% since the end of 2019. Right about that time, the Fed got alarmed and began to shrink the balance sheet (and hike rates, although you will notice that the price of money does not show up on this chart but only its quantity!) That, combined with some decent growth, has decreased the pent-up pressure on prices. As of the end of 2023Q3, the aggregate M/Q change was 26.2%, while core prices had risen 16.4% (headline prices, including a 33% increase in energy and a 25% increase in food prices, are up 19.5% since the end of 2019).

If the money supply grows only at the rate of GDP from here, then this line will turn vertical and we have about a 10% increase in core inflation to ‘makeup’ before we are back on the line. The good news is that the Fed currently is still reducing its balance sheet; the bad news is that M2 since April has stopped declining. More bad news is that GDP is likely to be soft or even negative here over the next few quarters, judging from payrolls, delinquencies, and other data. We could also hold out hope that velocity won’t fully rebound to pre-COVID levels, but there’s no reason other than “it sure would be nice if that happened” to expect that. Ergo, I think we’re still looking at higher-for-longer not just in the interest rate structure, but in the trajectory of inflation.

The most astonishing point on the charts above, in my mind, is the Japan point especially on the first chart. The amazing part is that Japan’s inflation rate is lower than that of other countries here. They’ve added less money, so as a first pass you’d expect less inflation. But what’s amazing is that the Yen is also an absolute basket case, which means that imports – like, say, oil or gasoline – have gone up a lot more in price than for other countries. Crude oil in USD has risen about 22% in USD terms since the end of 2019. It’s up 66% in Yen terms! And yet, even with that Japanese inflation has stayed relatively low. So far. These charts tell me that I’d want to buy Japanese inflation and sell EU and UK inflation, where prices are closer to already reflecting the effect of the money geyser than they are in Japan.