In late 2022, I often said that while I didn’t think it would be severe I figured we would have a recession in 2023 because we had never seen an energy spike at the same time that the Fed was aggressively tightening and not had a recession. Indeed, it would be weird if those things could happen and not result in a recession. Then, what causes a recession?!?

And as we all know by now, 2023 was not a recession. So, like any good trader who makes a bad call, I want to look and figure out why that happened. The funny thing is I wasn’t completely wrong on that.

We need to continue to remember that the volatility of 2020-2022 is something that doesn’t just vanish; the oscillations echo and repeat with slowly decreasing amplitude. The story of those years was this:

The economy was mostly shuttered in mid-2020, and the federal government and Federal Reserve showered money on consumers and businesses. Because service providers were basically closed, the money was poured into goods. This surge in demand led to long port delays and lead times, higher prices for goods, and a boom time for manufacturing.

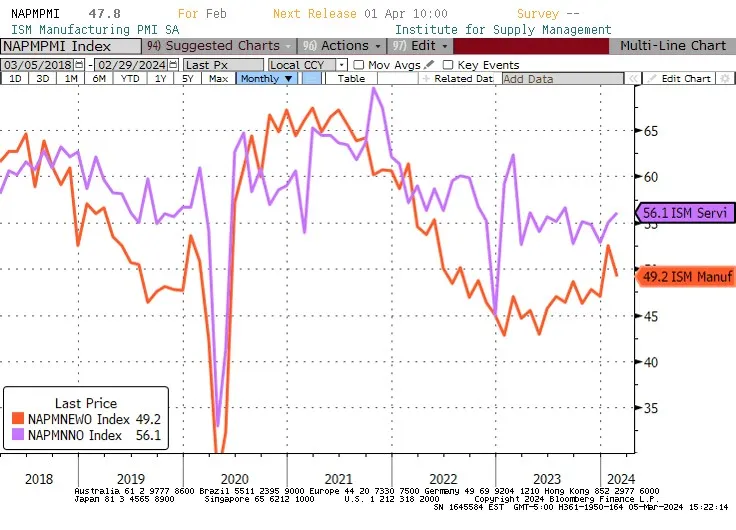

In the chart below, the orange line is the ISM Manufacturing New Orders index where 50 represents a dividing line between expansion and contraction (it’s a survey, so it’s not absolute levels but rather the change that is noted by respondents).

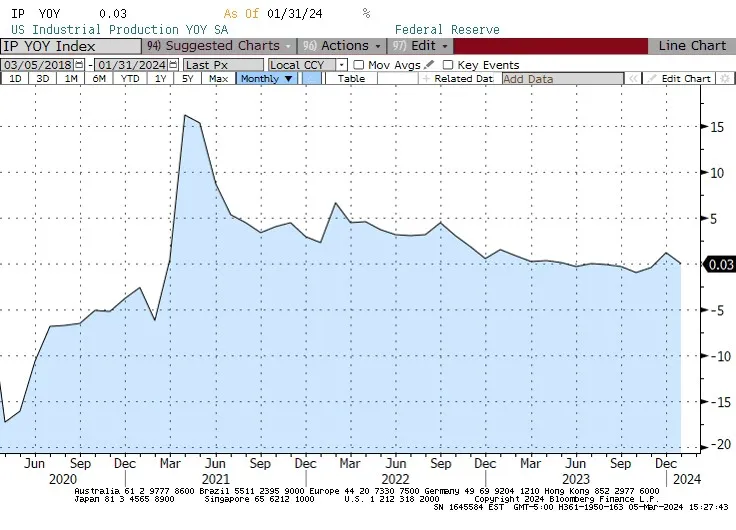

We can also see the boom in industrial production in the next chart. The y/y increase in production was at 4% or 5% until late 2022.

In March 2022, the Fed hiked 25bps. They did 50bps in May, 75bps in June, another 75bps in July, and of course, they kept going. Crude crested at $123/bbl in June. So by late summer of 2022, goods production started to see this in declining orders (first chart) and weakening production growth (second chart).

My sources in the industry started to see a buildup in client inventories, leading to lower orders – the celebrated ‘bullwhip’ effect. By late 2022 and for much of 2023, manufacturing was absolutely in a recession. The Conference Board’s Index of Leading Indicators had gone negative m/m in March 2022 and actually is still negative today.

Normally, that set of events would have produced a recession. But they didn’t. Why? Because the reopening of service industries was gathering steam over 2022. Remember that lots of restaurants were not allowed to operate at full capacity until the second half of 2021.

You can see the purple line in the chart above jumped higher late in 2021 and from the middle of 2022 remained above the goods-producing orange line. (“New Orders” for services industries is a more complicated concept, but you get the point).

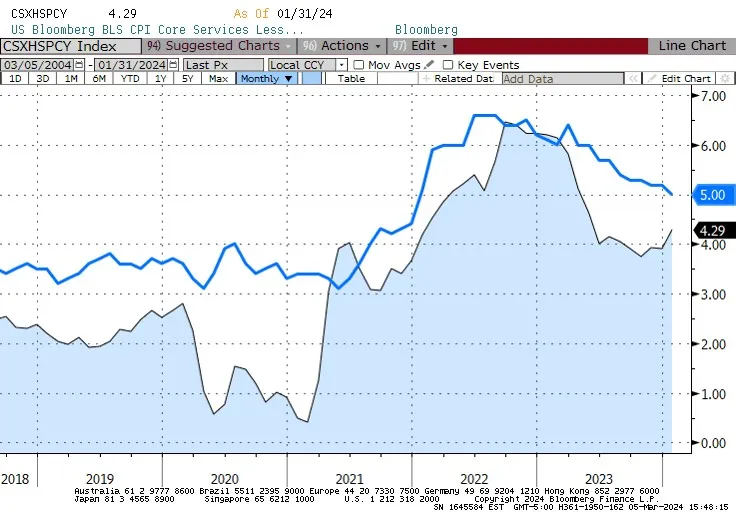

Remember how difficult it was for many service providers to find employees willing to work, and the spike in wages that was necessary to lure them? Well, you don’t have to remember, because here’s a chart showing wage growth for services employees (Atlanta Fed Wage Growth Tracker for services, in dark blue) against ‘Supercore’ core-ex-shelter CPI.

The later blooming of services, and the difficulty of service providers to build up capacity, stretched out the services expansion so that while manufacturing was in a recession, services were in an expansion. And, since services are a much larger part of the US economy, this meant that we never recorded an actual recession on overall growth. Moreover, the decline in goods prices helped flatter the increase in pressure on services prices, so that inflation measures turned lower while inventories were being right-sized.

Now, we are starting to see manufacturing start to turn higher – that orange line in the first chart popped above 50 in January and retreated to just below it in February. This is consistent with what I am hearing from my contacts, who are being more discerning about responding to this increase in demand by greatly expanding capacity (and then possibly being burned again).

It means that goods prices are no longer falling, and in many cases are rising again. I do think that there are some signs of consumer stress, such as auto loan delinquencies, and the purple “New Orders (Services)” line in the first chart looks to be slowly decelerating.

So I think it’s possible that this year we actually do get a recession, but I think it will be mild because manufacturing is oscillating in the upward direction now. That oscillation means that growth will not be as soft as it would be if services and goods were synchronized, which is one reason I believe this will be a mild or ‘garden variety’ recession the likes of which we haven’t seen in a while.

Eventually, the two parts of the economy will re-synchronize, but the way the reopening happened is I think why the macro call has been so difficult.