No sooner had the Federal Reserve released its statement on monetary policy yesterday, with the word “patient” removed than the stock market spiked.

But a close reading of the statement indicated policymakers were less impatient than many in the market to start cutting rates.

The statement kept language about sustained expansion, the strong labor market and inflation near its target as likely outcomes, but instead of concluding—as it did after the last meeting—that patience was warranted, it warned that “uncertainties about this outlook have increased.”

Increased to the point that the Federal Open Market Committee (FOMC) is now watching closely and “will act as appropriate to sustain the expansion.”

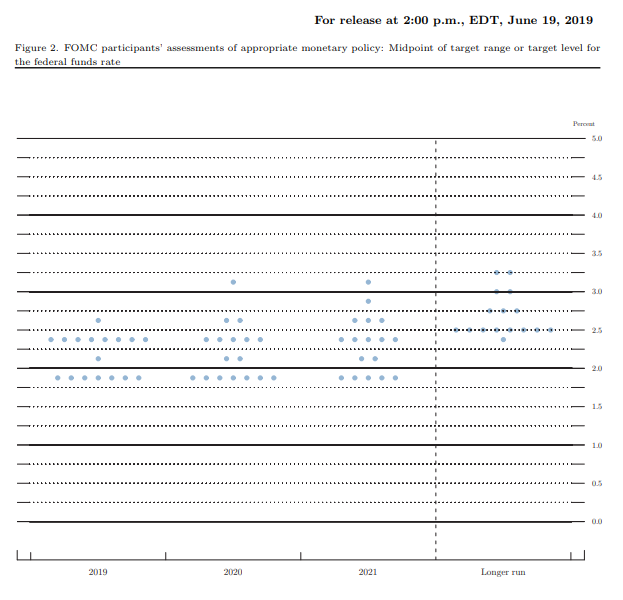

The dot-plot graph in the projection materials showed a divided committee, with the decision to cut rates by the end of this year on a razor’s edge.

Eight of the 17 policymakers forecast at least one cut this year, with seven of them seeing two cuts to 1.75-2.00 from the current 2.25-2.50 range in the fed funds. But eight of them expected rates to be unchanged at the end of the year and one even predicted a hike to 2.50-2.75.

The balance shifted for next year, with nine foreseeing at least one cut and seven still expecting two. Nobody was willing to go lower than that, and the majority expected the benchmark rate to return to at least 2.25-2.50 in 2021.

Fed chair Jerome Powell downplayed the dot-plot graph at the press conference following the meeting. He said they are individual projections and not something the committee even discusses. He warned against letting them distract from the whole picture—namely, that the committee would respond to incoming data to sustain the expansion and meet its objectives on inflation and employment.

But the Fed’s stubborn refusal to acknowledge the consistent failure of inflation to near its 2% target left many of the journalists puzzled. The statement said that overall inflation and core inflation was running below 2%, and market-based measures of inflation compensation have declined.

So one of the questioners asked, in essence, why don’t you do something about it. Powell mumbled something about more data coming in, thus still fairly patient after all.

The press conference neared satire level when one journalist asked whether the Fed would consider a recommendation made at last week’s strategy conference in Chicago to target 4% inflation as a way of getting it higher. Powell answered that wouldn’t be practical because they’re having a lot of trouble even getting it to 2%.

Powell registered the first dissent as chairman when St. Louis Fed chief James Bullard voted against leaving rates unchanged, preferring instead to cut them 0.25 percentage points at this meeting. Bullard spoke out against the interest rate hikes last year, but he was not a voting member, only rotating into a voting position this year.

On balance, investors were reasonably assured that the Fed would indeed take action if deleterious effects from trade tensions or other “crosscurrents” materialized. The statement and Powell’s remarks may have been less dovish than some would have wished, but the Fed was clearly at pains not to whip up any hopes for a market already too enthusiastic about the prospect of rate cuts. Stocks closed off their highs, but higher.

Fed futures indicated a 100% chance of a cut at the late-July meeting, and a greater likelihood of a second cut in September. By December, chances are given as better than even of a third cut, to 1.50-1.75 or lower.

As Powell said last week in Chicago with regard to the dot-plot graph, the decisions made reflect the views of policymakers right now, but that can change. The forecasts on rates is what participants will do if things go as expected.

“But we have been living in times characterized by large, frequent, unexpected changes in the underlying structure of the economy,” Powell said in Chicago. “In this environment, the most important policy message may be about how the central bank will respond to the unexpected rather than what it will do if there are no surprises.”

In short, he said then, urging market participants not to be distracted by the median forecasts of the dot-plot, “In times of high uncertainty, the median dot might best be thought of as the least unlikely outcome.”

So the Fed chair devoted to plain speaking is devising a little Fedspeak of his own.