While everyone was focused on the Federal Reserve’s bond purchases, policymakers slipped in a not-so-subtle surprise at last week’s meeting of the Federal Open Market Committee with their projection of an earlier rate increase.

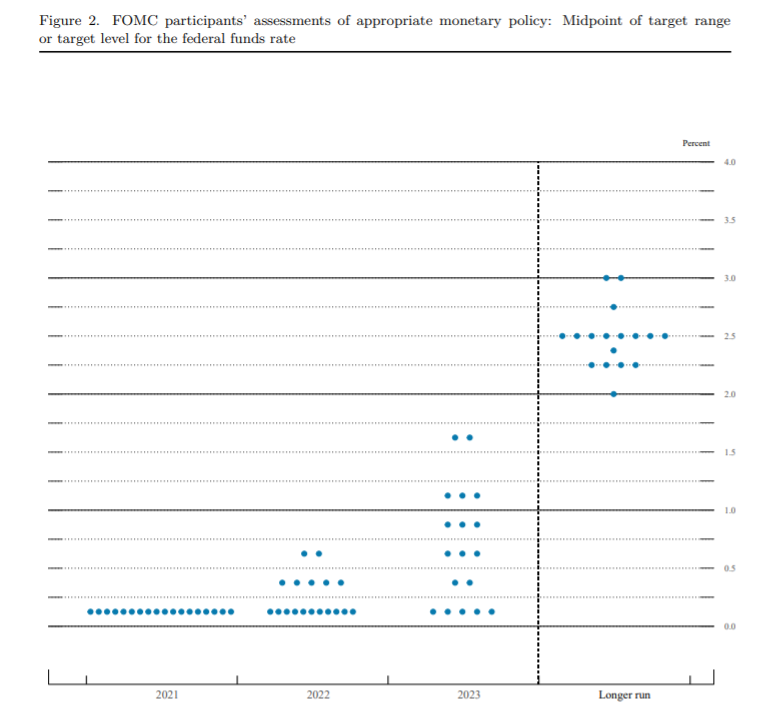

After maintaining for months that there would be no rate increases through 2023, FOMC members shifted their views and suddenly a preponderance of the 18 members—13 to be precise—projected an initial increase in 2023 or sooner, and seven now expect the first increase to take place in 2022, according to the individual forecasts on the famous dot-plot graph.

One of those apparently is St. Louis Fed chief James Bullard. He told CNBC on Friday that he now expects rate hikes to start in late 2022 as inflation picks up faster than they anticipated.

“We’re expecting a good year, a good reopening. But this is a bigger year than we were expecting, more inflation than we were expecting,” Bullard said. “I think it’s natural that we’ve tilted a little bit more hawkish here to contain inflationary pressures.”

In fact, last week’s median projections put inflation this year at 3.4%, as measured by the personal consumption expenditure index, compared with just 2.4% forecast in March, which itself was up from 1.8% in December. GDP growth is now projected at 7.0%, up from 6.5% in March and 4.2% in December.

See the trend?

At his press conference following the FOMC meeting, Fed Chairman Jerome Powell acknowledged that inflation has increased “notably” in recent months, and supply bottlenecks have been larger than anticipated.

But the Fed wizards still see this as transitory, and the median inflation projection for 2022 is 2.1% and for 2023, 2.2%. Bullard, for his part, sees inflation at 2.5% next year.

Investors reacted to the FOMC news by selling off both stocks and Treasuries, though the spike in Treasury yields was short-lived.

However, analysts cautioned there will be more volatility in the markets amid heightened sensitivity to inflation and GDP reports.

Fed officials have said they would begin and probably end tapering of their bond purchases before hiking rates, so an earlier date for starting rate increases means an earlier date for tapering.

No Longer Talking About Talking About Tapering

Thankfully, Powell suggested it was time to “retire” his quip about when policymakers would talk about talking about tapering—they are talking about it. But he still maintained that the committee needs to see more data before deciding when to slow down its current rate of buying $80 billion in Treasuries and $40 billion in mortgage securities each month.

Analysts now expect some indication of the timeline by the late August symposium in Jackson Hole, Wyoming, or at the FOMC meeting in September. As housing prices skyrocket amid low inventory, most economists expect the Fed to scale back its purchases of mortgage securities first. Some fear that the Fed is creating a bubble in housing prices with its hesitation.

The European Central Bank seems to be in sync with the Fed and reiterated earlier this month it will maintain easy monetary policy. One maverick central bank governor, Norway’s Øystein Olsen, has been brave enough to break with this groupthink and say that it’s time to put on the brakes.

The Norges Bank’s monetary policy committee kept rates unchanged at zero last week, but Olsen told a press conference afterwards that increases are coming this year.

“Given the rate path we see now, rates will be raised by 0.25% in (each of) the next four quarters,” he said, starting in September.

Norway has leeway because not only is it not part of the eurozone subject to the ECB, it is not even part of the European Union, so it has kept its own currency, its own central bank, and its own monetary policy. (Due to North Sea oil, the country also has the world’s largest sovereign wealth fund, with more than $1 trillion.)

Economists attributed Norway’s accelerated rate hikes to higher growth forecasts and inflation in housing prices.

Where else do we see these phenomena?