Journalists were visibly frustrated with Federal Reserve Chair Jerome Powell over his stubborn insistence that inflation—despite all the evidence to the contrary—would soon reach the Fed’s goal of 2 percent, during his press conference on Wednesday after the Fed's interest rate decision was announced.

With the economy humming along, growth clearly recovering, unemployment remaining low, job creation more than adequate to absorb new entrants to the labor market, and inflation not a worry, everything is “consistent with continued patience in assessing further adjustments in monetary policy,” Powell said in his opening remarks following the two-day meeting of the Federal Open Market Committee (FOMC), after it voted to leave monetary policy unchanged.

As a result, Powell offered little solace to President Trump or anyone else who was hoping for a cut in rates anytime soon. “We do think our policy stance is appropriate right now,” he said. “We don’t see a strong case for moving in either direction.”

Investors, many of whom had been speculating that the Fed’s next move might be to cut rates, sold off stocks at the news.

The key to Powell’s stance was this firm belief that 2-percent inflation is just around the corner. “Our baseline view remains that, with a strong job market and continued growth, inflation will return to 2 percent over time and then be roughly symmetric around our longer-term objective,” Powell said.

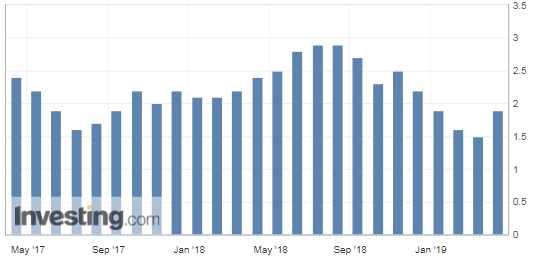

Reporters tried repeatedly, to no avail, to get him to go beyond that statement. Noting that inflation has hardly ever been over 2 percent in the past seven years, they wanted to know how persistent low inflation would have to be to get the Fed to act. Also, by the way, what could the Fed do to raise inflation if it ever decided it needed to do something?

Powell avoided answering these questions. After all, it is the committee’s firm belief that inflation will at some point reach 2 percent and even top it with the Fed’s blessing so that its target will be “symmetric” – sometimes below 2 percent, sometimes above.

FOMC policymakers noted that inflation since the beginning of the year has been “somewhat weaker” than they expected, Powell acknowledged, but committee members “suspect some transitory factors may be at work.”

What transitory factors, journalists wanted to know. Well, for instance, portfolio management fees were going to be lower in the first quarter reflecting the drop in asset values at the end of last year. And, and...apparel prices. Jiggering with the calculation for these prices impacted the inflation rate, Powell suggested.

That would have to be a fairly sizable impact for overall inflation to register only 1.5 percent and core inflation, stripping out volatile food and energy prices, coming in more surprisingly at 1.6 percent. That’s the Fed’s preferred measure, personal consumption expenditure index, which also showed a 1.3 percent quarter-over-quarter reading on core inflation in the first quarter.

For the Fed, it seems, it's always transient factors keeping inflation low. Powell refused to address the question of how many transient factors add up to persistently low inflation.

But he did offer a sop for all those frustrated journalists. If the data from the PCE doesn’t really back up the Fed’s arguments, how about the “trimmed mean PCE inflation rate”? This measure, tracked by the Dallas Fed, trims big movements both up and down to calculate the “mean” inflation. By that measure, inflation did not go down in March, though it, too, remained under 2 percent, as it has for most of the last several years.

In retrospect, one journalist wanted to know, do you think if you had not raised interest rates last year, inflation would have risen to your target?

Powell began his answer with “if you remember, at the time,” ignoring the “in retrospect” aspect of the question. At the time, Powell would have it, it seemed like a good idea to raise rates and preempt the inflationary pressures that were bound to be building, even though there was no evidence of them. Perhaps at some future conference then, Powell will be saying, at the time it seemed like a good idea to leave rates unchanged.