As the Fed tightens monetary policy, a banking crisis is historically the first evidence that something was breaking. As noted recently in “Not QE,”

“Last week, amid a rash of bank insolvencies, government agencies took action to stem a potential banking crisis. The FDIC, the Treasury, and the Fed issued a Bank Term Lending Program with a $25 billion loan backstop to protect uninsured depositors from the Silicon Valley Bank failure. An orchestrated $30 billion uninsured deposit by eleven major banks into First Republic Bank (NYSE:FRC) followed. I suggest those deposits would not occur without Federal Reserve and Treasury assurances.

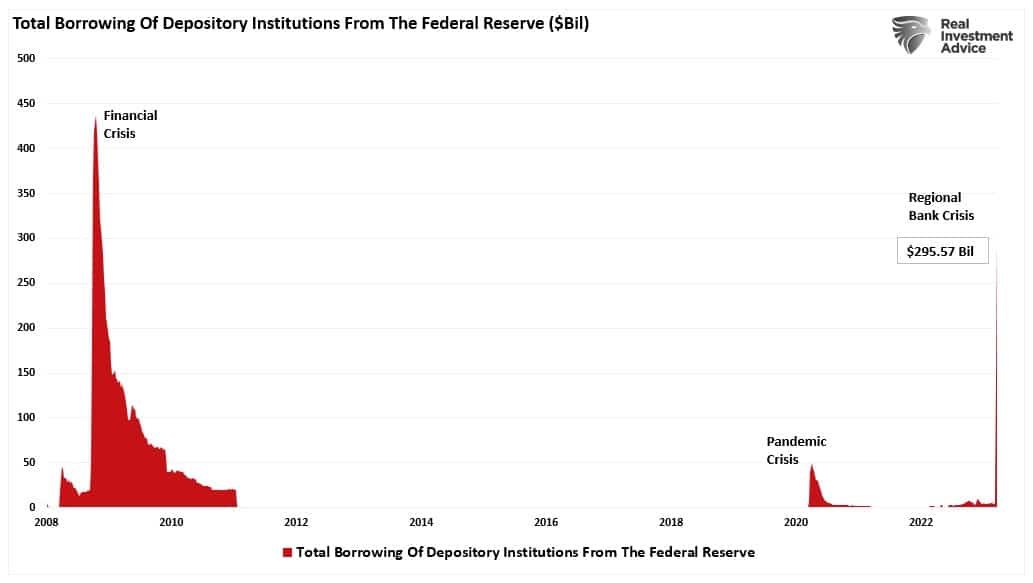

Banks quickly tapped the program, as shown by the $152 billion surge in borrowings from the Federal Reserve. It is the most significant borrowing in one week since the depths of the Financial Crisis.“

Since last week, that number has surged to almost $300 billion.

Since then, UBS entered into a “shotgun marriage” with Credit Suisse (SIX:CSGN), and the Federal Reserve reopened its dollar swap lines to provide liquidity to foreign banks.

“The Bank of Canada, the Bank of England, the Bank of Japan, the European Central Bank, the Federal Reserve, and the Swiss National Bank are today announcing a coordinated action to enhance the provision of liquidity via the standing U.S. dollar liquidity swap line arrangements.

To improve the swap lines’ effectiveness in providing U.S. dollar funding, the central banks currently offering U.S. dollar operations have agreed to increase the frequency of 7-day maturity operations from weekly to daily. These daily operations will commence on Monday, March 20, 2023, and will continue at least through the end of April.

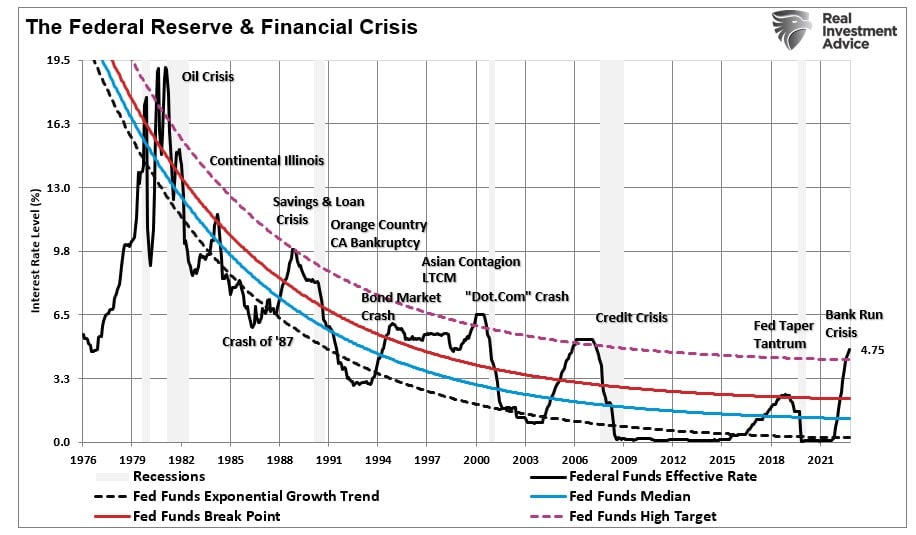

Historically, once the Fed opens dollar swap lines, further monetary accommodations follow from rate cuts to “quantitative easing” and other liquidity operations. Of course, such is always in response to a banking crisis, credit-related event, recession, or a combination.

While the “pavlovian response” to a reversal of monetary tightening is to buy risk assets, investors may want to take some caution as recessions tend to follow a banking crisis.

Banking Crisis Cause Recessions

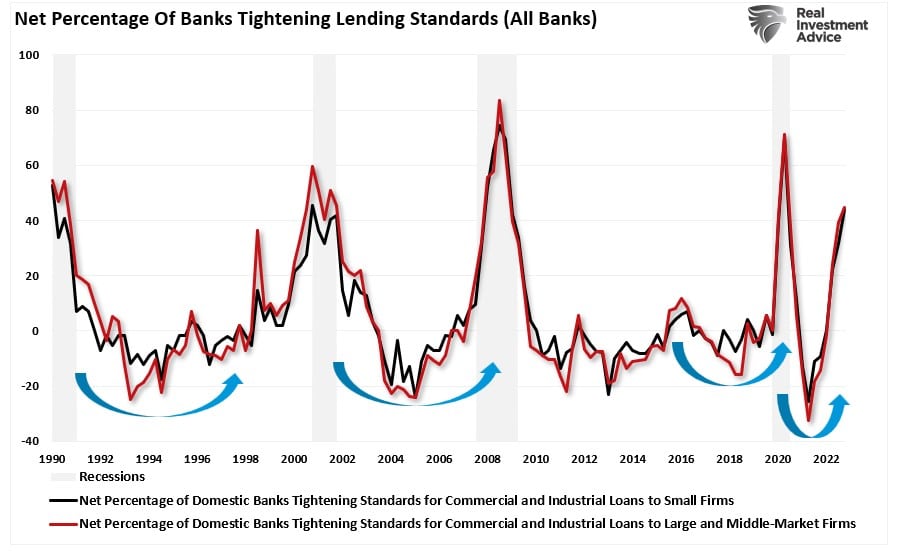

An obvious consequence of a banking crisis is a tightening of lending standards. Given the “lifeblood” of the economy is credit, both consumer and business, the tightening of lending standards reduces that economic flow.

Not surprisingly, when banks tighten lending standards on loans to small, medium, and large firms, liquidity constriction ultimately results in a recessionary drag. Many businesses rely on lines of credit or other facilities to bridge the gap between manufacturing a product or service and collecting revenue.

For example, my investment advisory business provides services to clients for a fee of which we collect one-fourth of the annual fee during each quarterly billing cycle. However, we must meet payroll, rent, and all other expenses daily or weekly. When unexpected expenses arise, we may need to tap a line of credit until the next billing cycle. Such is the case for many firms where there is a delay between the sale of a product or service and the billing cycle and collection.

If lines of credit are withdrawn, businesses must lay off workers, cut expenses, and take other necessary actions. The economic drag intensifies as consumers cut spending, further impacting businesses due to reduced demand. This cycle repeats until the economy slips into a recession.

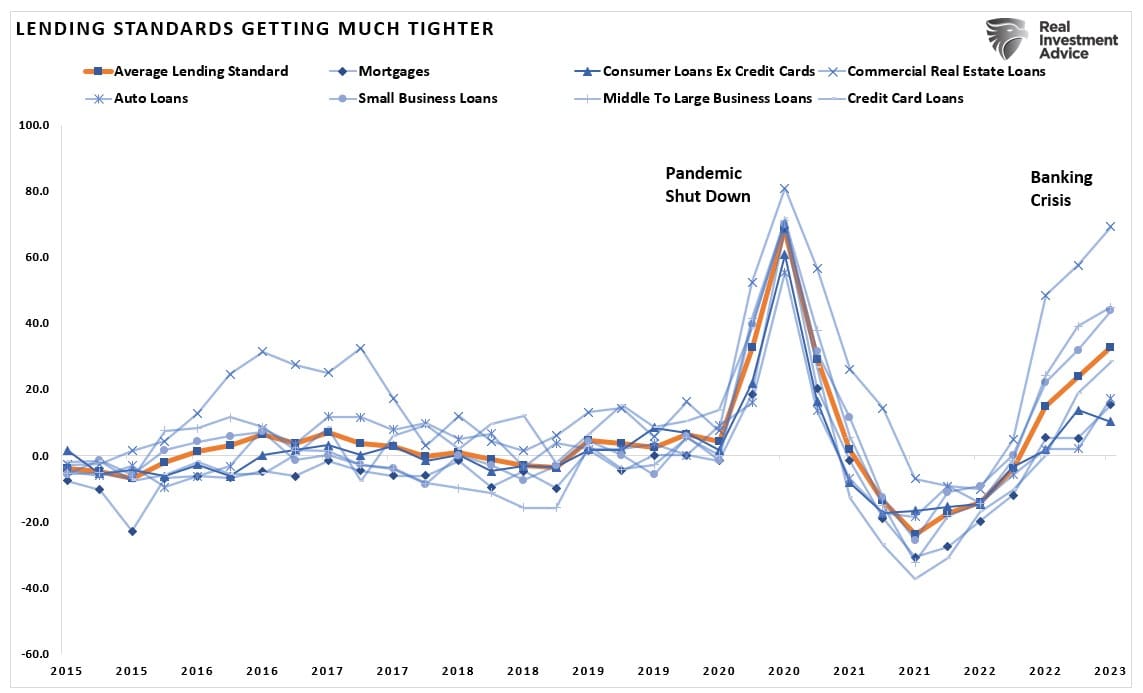

Currently, liquidity is getting extracted across all forms of credit, from mortgages to auto loans to consumer credit. The current banking crisis is likely the first warning sign of a worsening economic situation.

The last time we saw lending standards contract this much was during the pandemic-driven economic shutdown.

Many investors hope a Fed “pivot” to loosen monetary policy to combat recession risks will be bullish for equities.

Those hopes may be disappointed as recessions initially cause “repricing risk.”

Recessions Cause Repricing Risk

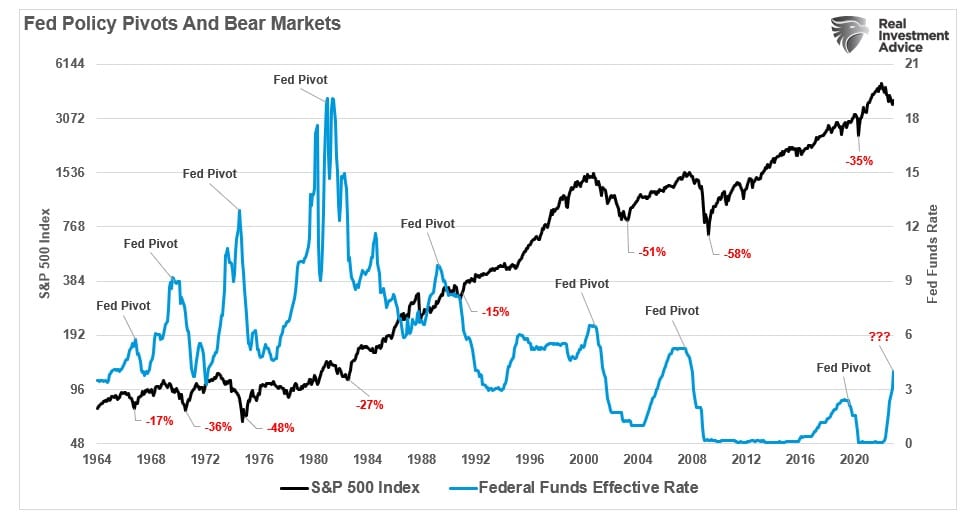

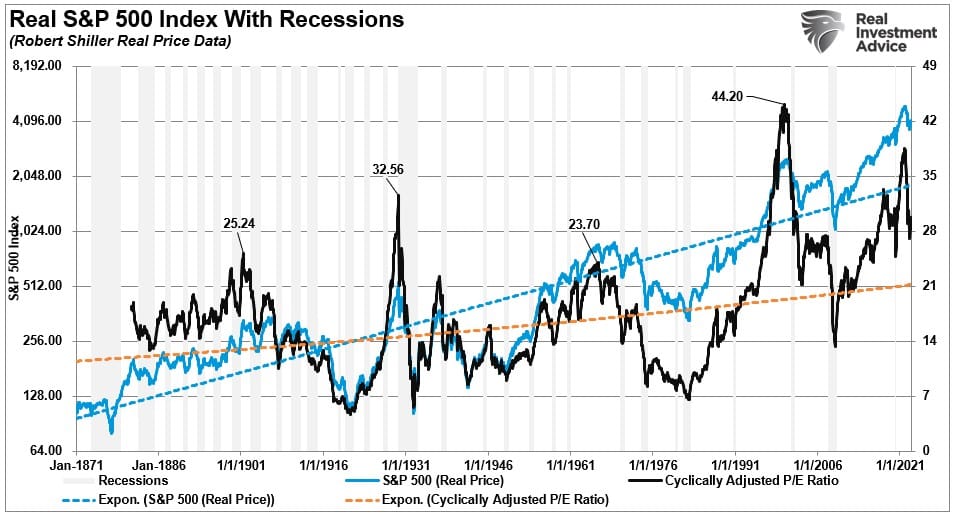

As noted, the bullish expectation is that when the Fed makes a “policy pivot,” such will end the bear market. While that expectation is not wrong, it may not occur as quickly as the bulls expect. When the Fed historically cuts interest rates, such is not the end of equity “bear markets,” but rather the beginning.

Notably, most “bear markets” occur AFTER the Fed’s “policy pivot.”

The reason is that the policy pivot comes with the recognition that something has broken either economically (aka “recession”) or financially (aka “credit event”). When that event occurs, and the Fed initially takes action, the market reprices for lower economic and earnings growth rates.

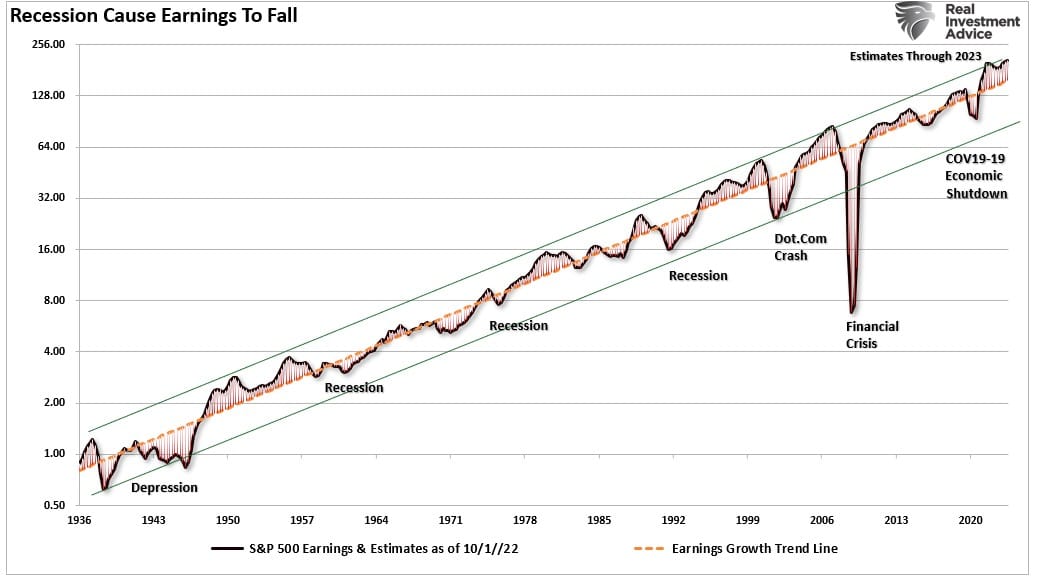

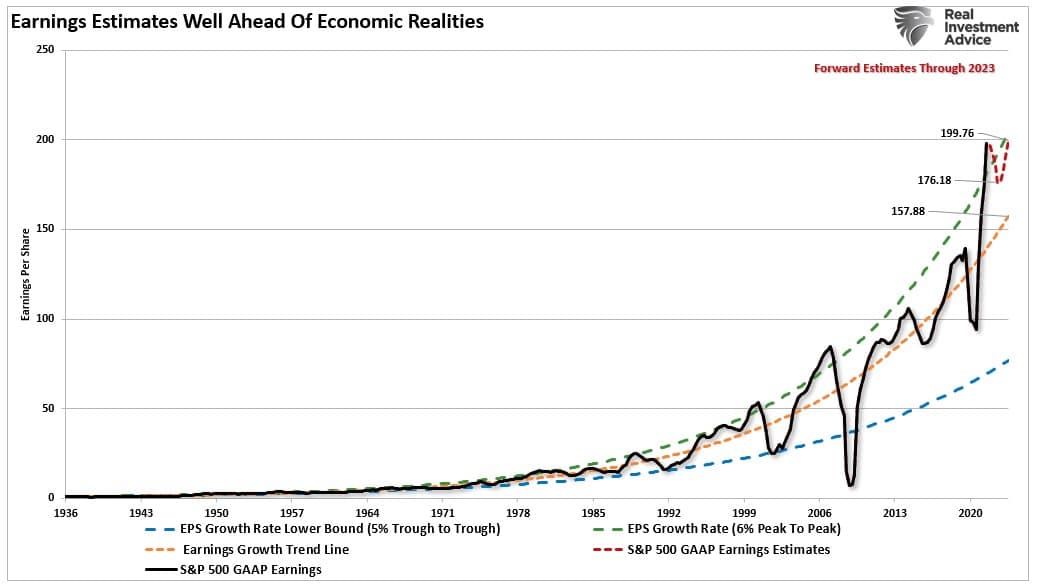

Forward estimates for earnings remain elevated well above the long-term growth trend. During recessions or other financial or economic events, earnings regularly revert below the long-term growth trend.

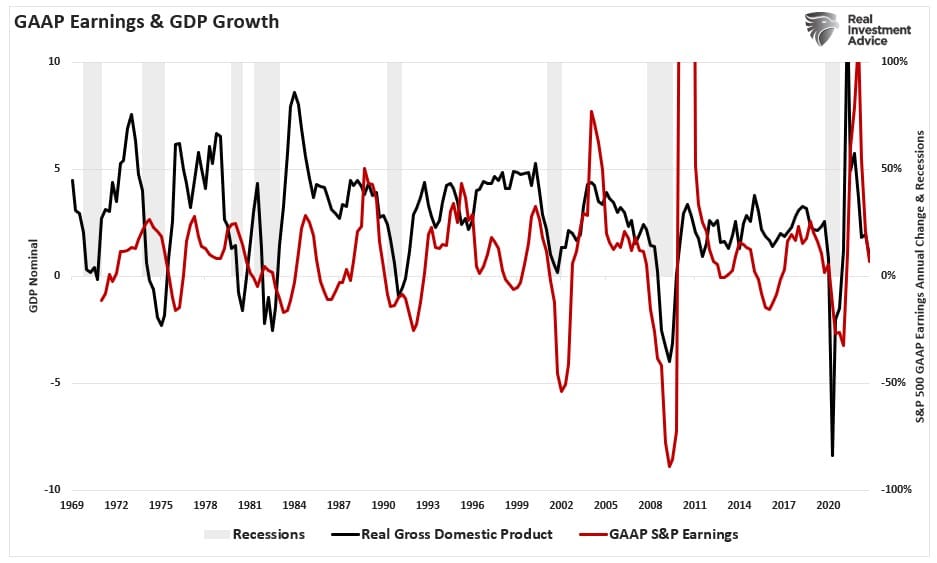

A better way to understand this is by looking at the long-term exponential growth trend of earnings. Historically, earnings grow roughly 6% from one peak earnings cycle to the next. Deviations above the long-term exponential growth trend are corrected during the economic downturn. That 6% peak-to-peak growth rate is derived from the roughly 6% annual economic growth. As we showed just recently, and of no surprise, the yearly earnings change is highly correlated to economic growth.

Given that earnings are a function of economic activity, current estimates into year-end are unsustainable if the economy contracts. That deviation above the long-term growth trend is unsustainable in a recessionary environment.

Therefore, given that earnings are a function of economic activity, valuations are an assumption of future earnings. Therefore, asset prices must reprice lower for earnings risk, particularly during a banking crisis.

There are two certainties facing investors.

- The Fed’s rate hikes started a banking crisis that will end in a recession as lending contracts.

- Such will force the Fed to eventually cut rates and restart the next “Quantitative Easing” program.

As noted, the first cut in rates will be the recognition of the recession.

The last rate cut will be the one to buy.