Austria has a storied history in the middle of Europe, but that’s not why investors oversubscribed its 100-year bond last week by nearly nine times, offering €17.7 billion ($19.91 billion) for the €2 billion ($2.2 billion) issue, which was priced to yield less than 1%—just 0.88% on a coupon of 0.85%.

A century is a long time, and no one pretends they can forecast just where Austria will be in a hundred years. Looking back a hundred years, the small republic that emerged from the shattered Austro-Hungarian Empire after World War I still had annexation by Hitler, occupation by the four powers, decades of neutrality and the European Union ahead of it.

So who knows where it will be in the next century. But that’s not the point. The rewards of investing in a 100-year bond are much more immediate.

A Bet On Fiscal Outlook; Potentially High Returns

The peculiarities of bond values make them attractive not only for pension funds with a long time horizon, but also for hedge fund speculators looking to make a quick buck.

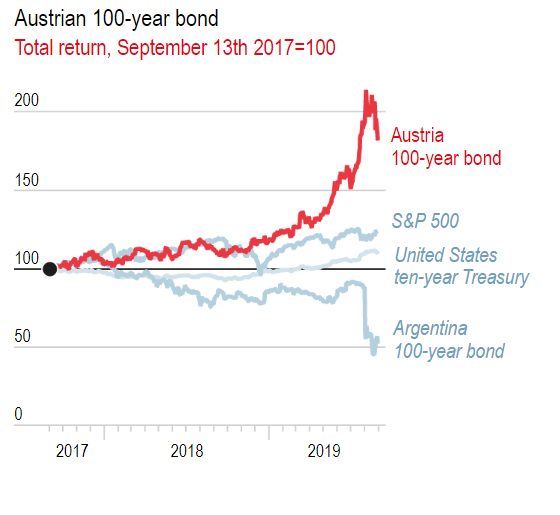

Chart courtesy: Economist

The 100-year bond Austria issued in 2017 has already returned 85% for investors, making it one of the highest-performing bonds in the market.

Although only a small portion of the sovereign bond market, ultra-long bonds are also interesting for what they tell us about the fiscal outlook. The bonds ultimately are bets that interest rates will stay low or decline further, that negative yields on high-rated government debt aren’t going away soon, that inflation risks becoming deflation, and that central banks need to find new tools for managing the economy.

The reason for the strong performance of ultra-long bonds is duration, a key concept for understanding how bonds are evaluated. Duration, as defined, is the weighted average of the payments an investor will receive over time, discounted to present value. The longer the payments period, the greater the return, even when discounted to present value.

This means super-long and ultra-long bonds are much more sensitive to even the smallest change in interest rates as duration amplifies the swings. Obviously, this is a two-edged sword, because duration will amplify losses as well as gains, but investors are attracted when, as now, they foresee a long period of low interest rates.

Who Benefits?

For the borrower—in this case, the country issuing the bond—the attraction is obvious. It's a chance to lock in a low rate for, well, a hundred years, rather than risk higher rates when it’s time to roll over the debt. It’s like a fixed-rate 30-year mortgage instead of an adjustable rate.

For pension fund investors, the long maturity gives them a chance to extend their own duration to get closer to having their assets match their liabilities. When they buy shorter-term bonds for liabilities that are 30 to 60 years out, they are exposed to interest-rate risk.

Austria issued its 2017, 100-year bond at par with a coupon of 2.1% and raised €3.5 billion. It reopened the issue a year ago to raise a further €1.25 billion, pricing the bonds this time at 154% to yield only 1.17%. That issue was oversubscribed four times.

The European Central Bank’s asset purchase program, augmented now by the emergency pandemic purchases, has brought Austria to the century market again, this time with a coupon and yield below 1%.

The low coupon brings an added benefit to investors because it leads to what is called positive convexity—prices rise more quickly when yields fall than they fall when yields rise.

The math underlying duration and convexity may be daunting, but the outcome is not. Ireland and Belgium have made private placements of 100-year debt, while France, Italy and the UK have ventured out with 50-year debt. On the other hand, Argentina’s 2017, 100-year 7.125% bond currently priced below $40 shows it can be a two-way street (see chart, above).

Among non-sovereign borrowers, a number of US universities—Caltech, USC, University of Virginia, Rutgers—have all issued 100-year bonds, at higher coupons and smaller amounts. Corporate borrowers include Walt Disney (NYSE:DIS) and Coca-Cola (NYSE:KO).

When sovereign borrowers come out with a century bond, it inevitably raises the question of whether the US will join the club.

Treasury Secretary Steve Mnuchin put a damper on that speculation in congressional testimony last month when he said that the government considered 50- or 100-year Treasurys for paying down a deficit expected to reach $3.4 trillion this year but found little demand for them.

Some have speculated that primary dealers, who have a vested interest in the frequent issue of shorter-term bonds, have convinced Mnuchin that there is not sufficient demand for an ultra-long bond. It’s hard to believe that investors ready to put up nearly $20 billion for tiny little Austria wouldn’t jump at the chance to buy a 100-year Treasury.

The US did auction $20 billion of 20-year bonds in May, for the first time since 1986, and Mnuchin said the government will focus on 10-, 20- and 30-year maturities. Looks like that’s about as ultra-long as Treasurys are going to get for now.