DXY blasted off again last night:

But the AUD fought the rise:

As Oil is rapidly filling upside gap:

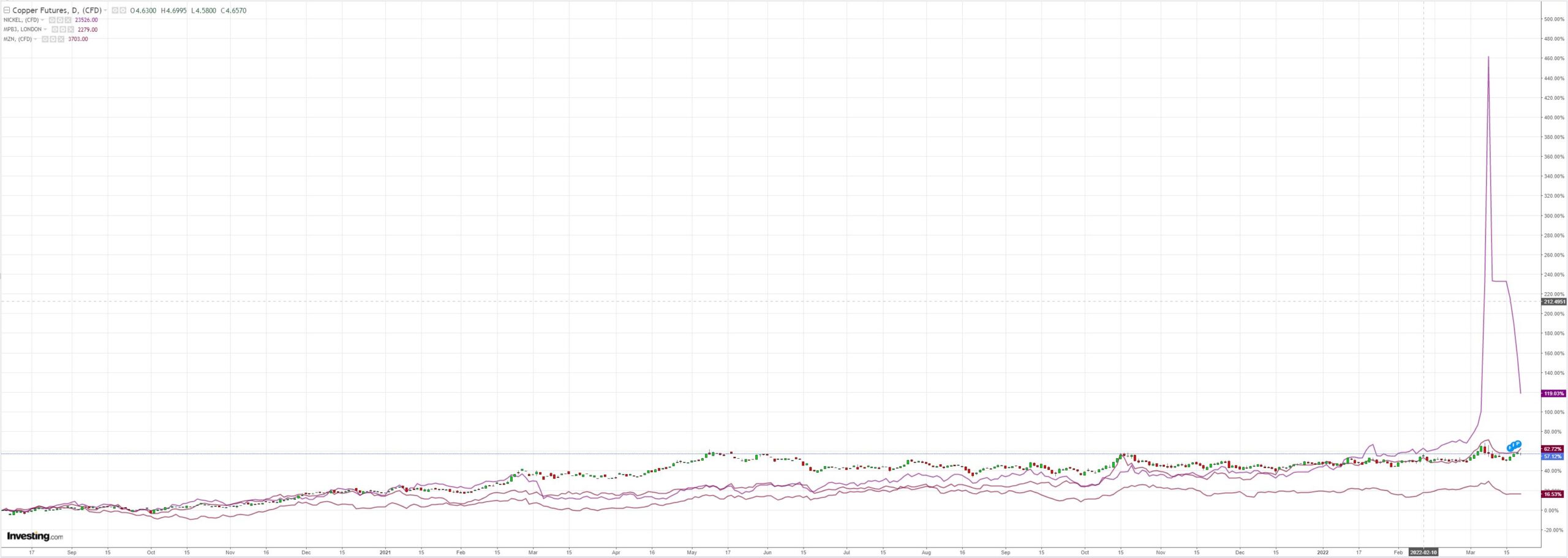

Metals not so much:

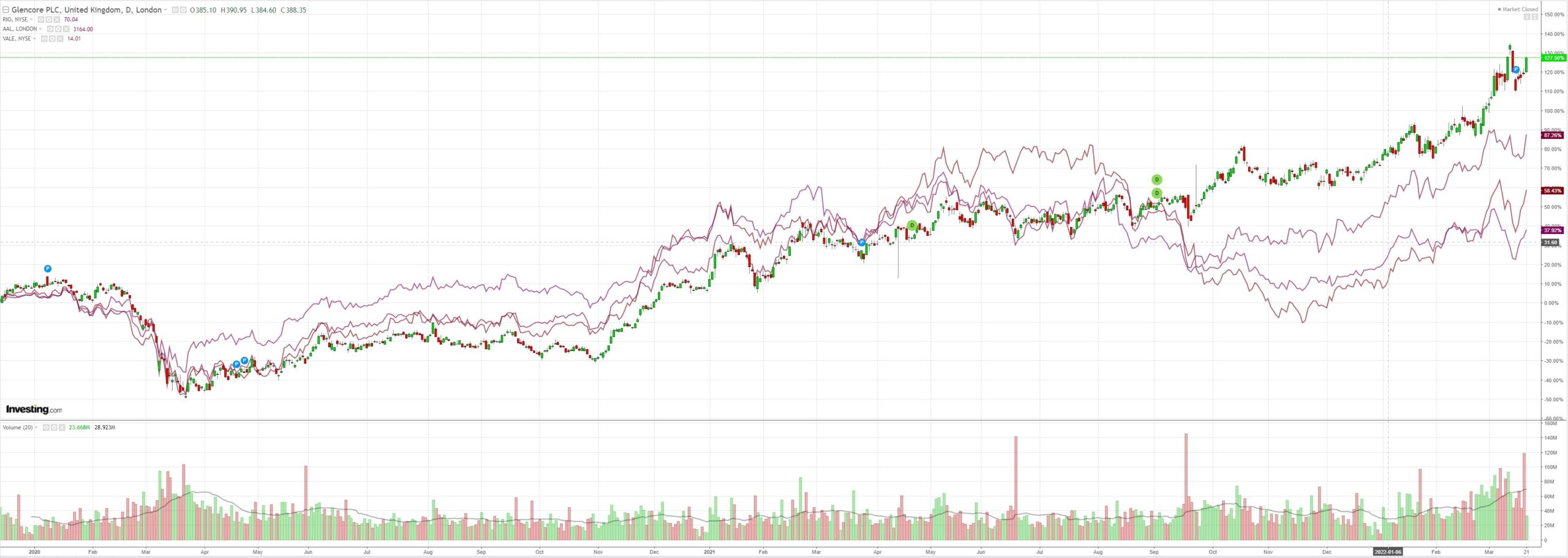

But miners (LON:GLEN) popped:

As EM stocks (NYSE:EEM) gave up:

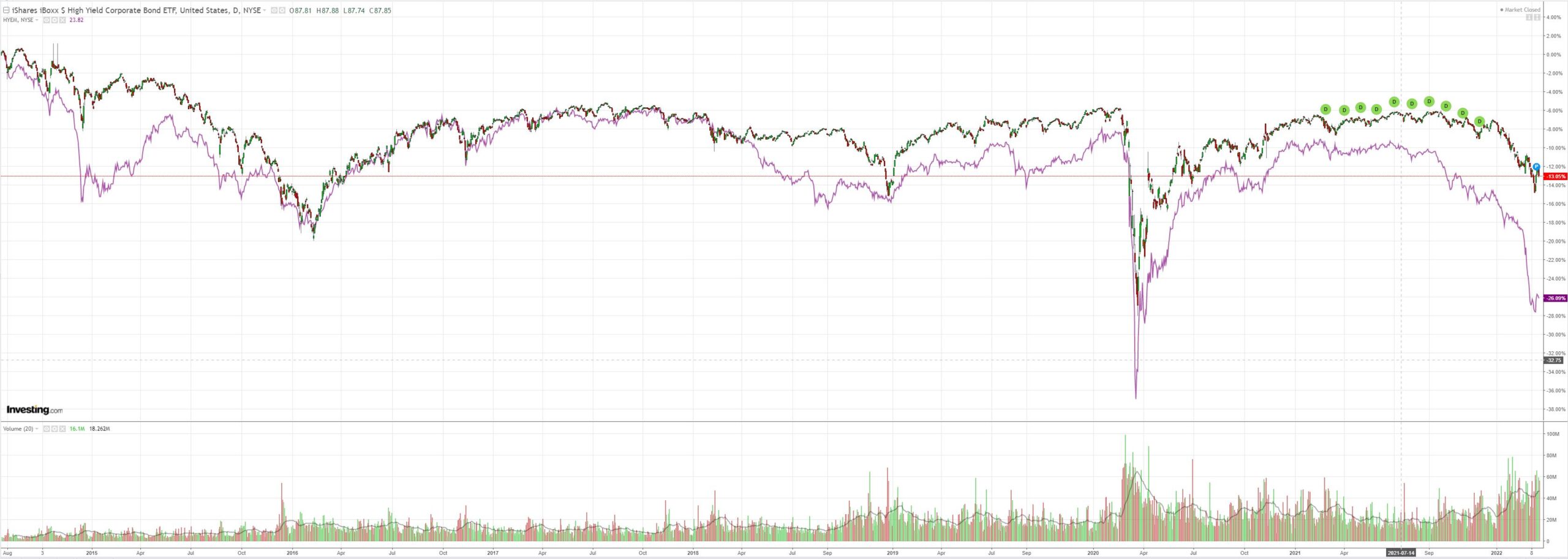

And junk (NYSE:HYG) told the tale:

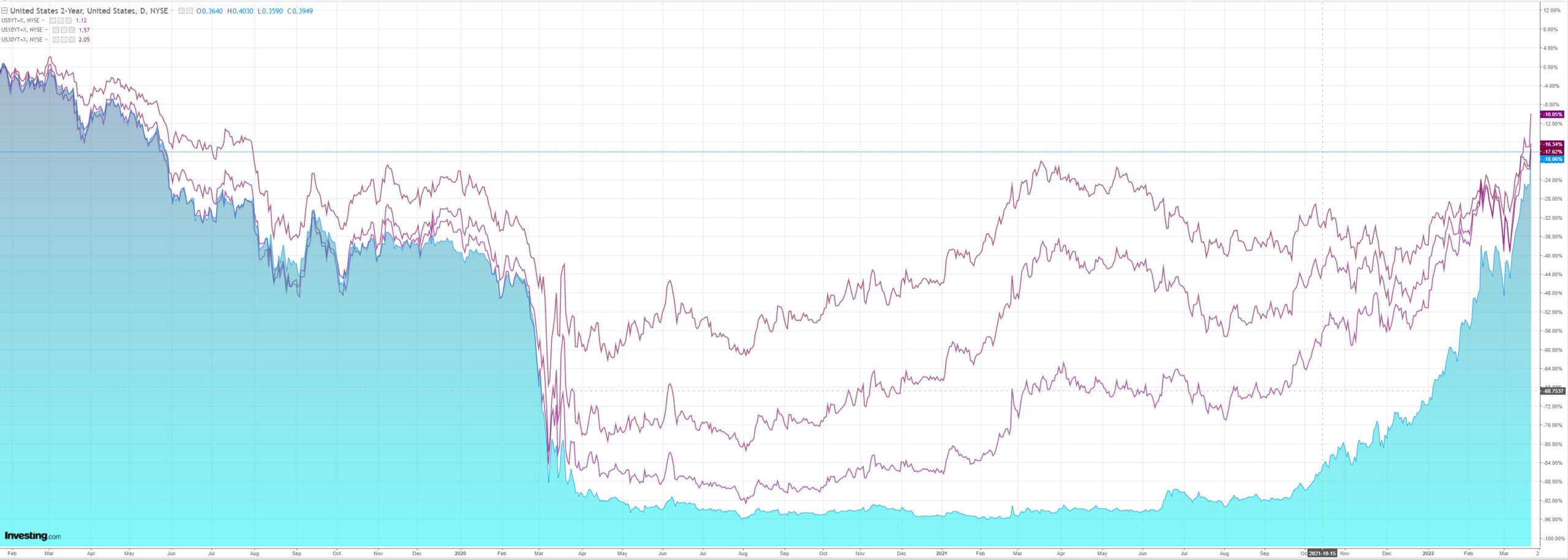

With huge spikes in yields inverting the curve from three years out. Recession anyone?

Yet stocks clung on:

Westpac has the wrap:

Event Wrap

Fed chair Powell’s comments were more hawkish than expected, emphasising the need to quell inflation rather than caution due to the risks to economic growth: “will take the necessary steps to ensure a return to price stability…in particular, if we conclude that it is appropriate to move more aggressively by raising the federal funds rate by more at a meeting or meetings, we will do so…if we determine that we need to tighten beyond common measures of neutral and to a more restrictive stance, we will do that as well.” He said the Fed’s previous view was for inflation to peak as supply chain distortions abated, but admitted that that view has “fallen apart” and if it continues to fall apart it might necessitate more aggressive action.

FOMC member Bostic agreed with the view on the committee that policy needs to get to neutral as quickly as possible. He estimates neutral around 2.25%, and expected six 25bp increases this year and two more in 2023. He also said that he is not wedded to 25bp moves, and that the Fed should act on the balance sheet soon.

The Chicago Fed National Activity Index was close to consensus at 0.51 (est. 0.50, prior revised from 0.69 to 0.59). The level suggests modest above-trend growth.

German PPI in February was slightly disappointing at +1.4%m/m and 25.9%y/y (est. +1.7%m/m, and 26.2%y/y).

Event Outlook

Aust: RBA Governor Lowe will make an appearance at the Walkley Awards for Business Journalism in Sydney at 12pm (no Q&A).

NZ: The Q1 Westpac-MM consumer confidence survey will provide a timely update on the consumer given the headlines surrounding omicron infections, energy inflation and the cooling housing market throughout the quarter.

US: Difficulties in sourcing labour remain as a headwind for manufacturing in the March Richmond Fed index (market f/c: 2). The FOMC’s Wuerffel, Williams and Daly are all due to speak at different events.

Jay Powell was super-hawkish in Congress:

Turning to price stability, the inflation outlook had deteriorated significantly this year even before Russia’s invasion of Ukraine.

The rise in inflation has been much greater and more persistent than forecasters generally expected. For example, at the time of our June 2021 meeting, every Federal Open Market Committee (FOMC) participant and all but one of 35 submissions in the Survey of Professional Forecasters predicted that 2021 inflation would be below 4 percent. Inflation came in at 5.5 percent.

For a time, moderate inflation forecasts looked plausible—the one-month headline and core inflation rates declined steadily from April through September. But inflation moved up sharply in the fall, and, just since our December meeting, the median FOMC projection for year-end 2022 jumped from 2.6 percent to 4.3 percent.

Why have forecasts been so far off? In my view, an important part of the explanation is that forecasters widely underestimated the severity and persistence of supply-side frictions, which, when combined with strong demand, especially for durable goods, produced surprisingly high inflation.

The pandemic and the associated shutdown and reopening of the economy caused a serious upheaval in many parts of the economy, snarling supply chains, constraining labor supply, and creating a major boom in demand for goods and a bust in services demand. The combination of the surge in goods demand with supply chain bottlenecks led to sharply rising goods prices (figure 4). The most notable example here is motor vehicles. Prices soared across the vehicles sector as booming demand was met by a sharp decline in global production during the summer of 2021, owing to shortages of computer chips. Production remains below pre-pandemic levels, and an expected sharp decline in prices has been repeatedly postponed.

Many forecasters, including FOMC participants, had been expecting inflation to cool in the second half of last year, as the economy started going back to normal after vaccines became widely available.3 Expectations were that the supply-side damage would begin to heal. Schools would reopen—freeing parents to return to work—and labor supply would begin bouncing back, kinks in supply chains would begin resolving, and consumption would start rotating back to services, all of which could reduce price pressures. While schools are open, none of the other expectations has been fully met. Part of the reason may be that, contrary to expectations, COVID has not gone away with the arrival of vaccines. In fact, we are now headed once again into more COVID-related supply disruptions from China. It continues to seem likely that hoped-for supply-side healing will come over time as the world ultimately settles into some new normal, but the timing and scope of that relief are highly uncertain. In the meantime, as we set policy, we will be looking to actual progress on these issues and not assuming significant near-term supply-side relief.

By implication, if the supply side is not going to loosen up, then the Fed is going crush the demand side to fit within those limitations.

Risk markets are fighting the Fed, AUD included.

It’s never a good idea for long.